A Quick Note: What Is EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION Good for?

Introduction

I came across a remarkably well-written article while bushing up on Structural Exception Handling (SEH) in preparation for this undertaking. Although slightly outdated, it will, definitely, be worth one’s while to read (if one has not done so already).

In this article, Matt Pietrek gives an example of an exception handler that eliminates the cause of an access violation exception by properly initializing the variable being accessed, thus preventing the error from reoccuring. Upon completing the damage control, this exception handler returns EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION to signal the OS that it is safe to repeat the instruction now.

Out of curiosity (assuming the reader is curious), let us try achieving the same effect.

The Experiment

To begin with, we need a function that would access some memory location, say, by dereferencing a (potentially unitialized/invalid) pointer. Let us attempt writing something ominous (for a dramatic effect) at the resulting address.

1

2

3

4

void do_potentially_dangerous_assignment(volatile int** ppAddr)

{

**ppAddr = 666; //666 == 0x29a

}

That will do. The use of double indirection will be justified shortly. Now, let us set up an exception handler and call do_potentially_dangerous_assignment() with a null-pointer as an argument.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

int main()

{

int temp = 0;

int* address = NULL;

__try {

do_potentially_dangerous_assignment(&address);

}

__except (filter(GetExceptionCode(), GetExceptionInformation(),

&address, &temp)) {

printf("Should never get here\n");

}

return 0;

}

Somewhat inconveniently, perhaps, the syntax of __try/__except block dictates that the fix be done in the exception filter.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

int filter(int n_except, _EXCEPTION_POINTERS* pep, int** ppaddr, int* ptemp)

{

if (n_except == EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION) {

printf("Attempting to fix the problem in filter() RIP=0x%llX Addr=0x%llX\n",

pep->ContextRecord->Rip, pep->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionAddress);

*ppaddr = ptemp;

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

}

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH;

}

The way the access violation is disposed of is by initializing the value of variable address with an address of variable temp (both variables are local to main()): *ppaddr = ptemp (line 8).

Now the reason why address is passed to do_potentially_dangerous_assignment() by reference rather than by value becomes apparent: we can change the pointer being dereferenced without restarting the function. In order to ensure a fresh value of address is picked up each time do_potentially_dangerous_assignment() executes *ppAddr, we declare this parameter as volatile.

With the exception filter in place, it is time to see the fix in action.

“Wait!!!” I already hear my readers shouting through the screen, “It won’t work!”, and this admonition is, of course, warranted. Here is the output we would get.

1

2

3

4

5

Attempting to fix the problem in filter() RIP=0x7FF7C76A1752 Addr=0x7FF7C76A1752

Attempting to fix the problem in filter() RIP=0x7FF7C76A1752 Addr=0x7FF7C76A1752

Attempting to fix the problem in filter() RIP=0x7FF7C76A1752 Addr=0x7FF7C76A1752

Attempting to fix the problem in filter() RIP=0x7FF7C76A1752 Addr=0x7FF7C76A1752

[...]

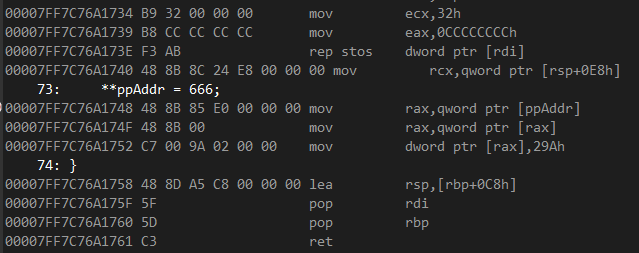

The program is stuck in an infinite loop as the system, following the exception filter’s directions, is initiating the faulty memory access over and over again, and each time it results in the same kind of exception. Evidently, the fix does not work. In order to understand why, one should examine disassembly listings. Here is what **ppAddr = 666 looks like disassembled:

The statement has been translated into a sequence of three instructions: mov rax, qword ptr [ppAddr], mov rax, qword ptr [rax], and mov dword ptr [rax], 29Ah, of which only the last one is executed repeatedly. Upon the exception handler returning EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION, the operating system happily sets RIP to the address of the last attempted instruction (mov dword ptr [rax], 29Ah) and lets the program loose. The fix has no effect for RAX remains set to zero; to make it work, a little adjustment is required.

Our exception filter accepts a structure EXCEPTION_POINTERS as a parameter. Inside it, there is the ContextRecord field that gives us the execution context, frozen at the the point in time when the exception occurred. What if we set ContextRecord->Rip to the address of the first instruction in the sequence? Provided Windows initializes RIP with the supplied value, the statement **ppAddr = 666 will be executed in its entirety, thereby enabling the correct value of address to be loaded. To this end, we must offset RIP by 0xA = 0x7FF7C76A1752 - 0x7FF7C76A1748

1

pep->ContextRecord->Rip -= 0xA;

WARNING:

Obliviously, the set of instructions **ppAddr = 666 translates into changes depending on the compiler, optimization settings, and target architecture. Do not use this technique in real-life projects. It is for demonstration only!

Below is the complete solution:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

#include <windows.h> // EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION

#include <excpt.h>

void do_potentially_dangerous_assignment(volatile int** ppAddr)

{

**ppAddr = 666;

}

int filter(int n_except, _EXCEPTION_POINTERS* pep, int** ppaddr, int* ptemp)

{

if (n_except == EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION) {

printf("Attempting to fix the problem in filter() RIP=0x%llX Addr=0x%llX\n",

pep->ContextRecord->Rip, pep->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionAddress);

*ppaddr = ptemp;

pep->ContextRecord->Rip -= 0xA;

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

}

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH;

}

int main()

{

int temp = 0;

int* address = NULL;

__try {

do_potentially_dangerous_assignment(&address);

}

__except (filter(GetExceptionCode(), GetExceptionInformation(),

&address, &temp)) {

printf("Should never get here\n");

}

return 0;

}

This time the fix does work! The program prints the error message once only, then terminates.

So this cumbersome trick does the job, but I cannot recall it being mentioned in the article. How come? How did the author get away with it? He did so by coding the relevant functions directly in assembler, thereby ensuring a single-instruction memory access operation is used to produce the exception.

Conclusion

As is, presented here is not a feasible approach due to the abysmal lack of portability and, therefore, it should not be used in practice in any shape or form (some other, more versatile, way of identifying the relative address of the fist instruction is needed). However, it “satiated” my curiosity to find out that it could be applied in principle.

– Ry Auscitte

References:

- Matt Pietrek, A Crash Course on the Depths of Win32 Structured Exception Handling, Microsoft Systems Journal, January 1997

- Ry Auscitte, Boots for Walking Backwards: Teaching pefile How to Understand SEH-Related Data in 64-bit PE Files (2021), Notes of an Innocent Bystander (with a Chainsaw in Hand)