Bringing My OS Back from the Abyss : Restoring Windows Registry (Part 3)

Introdution

The previous installment in the series identified corrupted registry as the reason behind Window’s failure to boot. This extraordinary (he-he) achievement was brought into being by first performing crash dump analysis (that allowed us to retrieve the error code recorded on stack as well as pinpoint a system dll and failing function within it), and then, after the said function had been reverse-engineered, locating the system call that, in all probability, resulted in an error. The system call turned out to perform a registry query and this is how we have gotten here.

“Heh! Baby girl,” you will, no doubt, say in reply, chuckling, “I would have bet my bottom dollar that the broken registry was the thing that would not let Windows boot without your fancy-schmancy bug-check analyses and reverse-engineerings.” Indeed, registry corruptions are to OS crashes as burnt capacitors are to electronics failures and one could definitely have saved some time by taking a shortcut and checking the registry for consistency right away. However, being methodical in performing troubleshooting procedures gives one a chance to gain a deeper insight into what is happening “under the hood” and, by this means, broaden one’s knowledge. On this note, let us begin.

“Wait a minute,” you might interject, “doesn’t Windows back up its registry every now and then?” It used to. Not anymore. According to the Microsoft’s documentation, starting from the build 1803, Windows 10 no longer maintains “spare” copies of its register hives which is “intended to help reduce the overall disk footprint size of Windows” (the backup files could still be found in the %SystemRoot%\System32\config\RegBack directory, but they are of zero size). Bugcheck analysis, along with other information, outputs this string: “BUILDDATESTAMP_STR: 180410-1804” for the system in question. I was one build too late! Now it is recommended that we use Windows restore points in case the registry needs to be restored to some earlier state.

For the record, the list of restore points turned out to be empty; Mocrosoft’s sfc utility had also been given a try, with the same, dismal, outcome.

Extent of the Damage

Now that we have exhausted the arsenal of quick fixes and delving into the depths of registry organization appears inevitable why not start off with a quick “extent of the damage” assessment? As was established beforehand, it was the attempt to query HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\IniFileMapping key that caused the booting process to halt. Windows Internals has the following to to say on the use of SOFTWARE hive in Windows 7: “HKLM\Software is where Windows stores systemwide configuration information not needed to boot the system.” Apparently, it is no longer true.

So, what else is missing? The sequence of Python statements below obtains a list of CurrentVersion’s subkeys that are found in the registry of WinRE, but not in the corrupt hive on the system that fails to boot (I am using Willi Ballenthin’s python-registry for this purpose).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Python 3.8.5 (default, Jan 27 2021, 15:41:15)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> from Registry.Registry import Registry

>>> reg_brk = Registry("/media/ubuntu/Data/WinRestore/RegBakup/SOFTWARE")

>>> reg_winre = Registry("WinRE_SOFTWARE")

>>> cv_brk = reg_brk.open("Microsoft\\Windows NT\\CurrentVersion")

>>> cv_winre = reg_winre.open("Microsoft\\Windows NT\\CurrentVersion")

>>> winre_sks = set([ sk.name() for sk in cv_winre.subkeys() ])

>>> brk_sks = set([ sk.name() for sk in cv_brk.subkeys() ])

>>> winre_sks - brk_sks

{'Svchost', 'Compatibility32', 'MiniDumpAuxiliaryDlls', 'AppCompatFlags', 'UnattendSettings', 'Winlogon', 'WinPE', 'ProfileNotification', 'Tracing', 'SeCEdit', 'Font Drivers', 'ProfileLoader', 'ASR', 'EFS', 'IniFileMapping', 'Windows', 'AeDebug', 'Schedule', 'Font Management', 'WbemPerf'}

Among them, notably, is Winlogon which includes as its values a set of parameters used to guide wininit.exe’s execution so, perhaps, the fact that wininit.exe promptly failed the moment we managed to fix csrss.exe) (see part II) should be not in the least surprising. One can learn about other missing keys here and decide on their importance.

Other subkeys, such as ProfileList (stores SIDs for user accounts) and Fonts (lists installed fonts) are present but contain neither subkeys nor values.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

>>> set([sk.name() for sk in cv_brk.subkey("ProfileList").subkeys()])

set()

>>> set([vl.name() for vl in cv_brk.subkey("ProfileList").values()])

set()

>>> set([vl.name() for vl in cv_brk.subkey("Fonts").values()])

set()

>>> set([sk.name() for sk in cv_brk.subkey("Fonts").subkeys()])

set()

Even a cursory glance at the listings above makes it obvious that replacing the absent data by hand will be rather tricky if not impossible. For example, do you happen to know, off the top of your head, the SID of your account? Me neither. No mean feat here, I am afraid. For this reason, the only viable way of fixing the registry consists in looking for the bits and pieces of the missing data on the hard drive and somehow stitching it back together into the HKLM\SOFTWARE hive. The latter could not be accomplished without at least a passing acquaintance with organization of Windows registry so let us dive in.

A Brief Excurse Into Internal Structure of Windows Registry

Internally the register is divided into so-called hives. One is tempted to assume the one-to-one correspondence between hives and HKEY_* groups, but very few things in this world (homework excuses, history textbook and the likes of them) could be farther from the truth. HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, for example, consists of not one, not two, and not even three, but four permanent hives: SAM, SECURITY, SOFTWARE, and SYSTEM. HKEY_PERFORMACE_DATA, on the other hand, is completely virtual and, as such, does not contain non-volatile hives at all. The notion of hive is somewhat vague; here is how it is defined in the official documentation:

A hive is a logical group of keys, subkeys, and values in the registry that has a set of supporting files loaded into memory when the operating system is started or a user logs in.

However, for all intents and purposes, it is helpful to think of hives as files on the hard drive (apart from volatile hives that exist in memory only), also known as hive primary files (the terminology is due to Maxim Suhanov). For example, the HKEY_LOCAL_MAHINE\SOFTWARE hive is stored as the file %SystemRoot%\System32\config\SOFTWARE. In addition to the primary file, there are two transaction log files: SOFTWARE.LOG1 and SOFTWARE.LOG2, and, possibly, SOFTWARE{<Guid>}.TM.blf, SOFTWARE{<Guid>}.TMContainer00000000000000000001.regtrans-ms, SOFTWARE{<Guid>}.TMContainer00000000000000000002.regtrans-ms – all residing in the %SystemRoot%\System32\config directory. The latter group of files is used by the common logging file system to implement transaction-based modifications to the registry and it is outside the scope of this discussion.

In order to ensure a non-volatile hive is always in a recoverable state Windows applies a dual-logging scheme. Registry modifications are kept in memory till a flush operation is initiated (as a result of an explicit API call or as a scheduled operation), then the “dirty” data is written to one of .log1, or .log2 files: say, .log1. If that fails, next time changes accumulated since the last successful write operation are flushed to the .log2 and in this manner the destination file alternates between .log1 and .log2 up until the point when one of the disk write operation succeeds. This is why there are two transaction log files.

Described above is only a half of the steps involved in saving the registry modifications to disk. In order to explain the rest two integers must be introduced: hive sequence number 1 and hive sequence number 2, both stored in the hive primary file and maintained equal. Once the “dirty” data is successfully written to one of .logN files, hive sequence number 1 is increased by one while hive sequence 2 retains its previous value; after that the same data is copied to the hive primary file. If Windows crashes mid-operation, mismatch between the two sequence numbers will instruct the OS to transfer the modifications from the transaction log to the primary file upon the next successful boot and update the second sequence number. As a result, the hive will end up being in a consistent state.

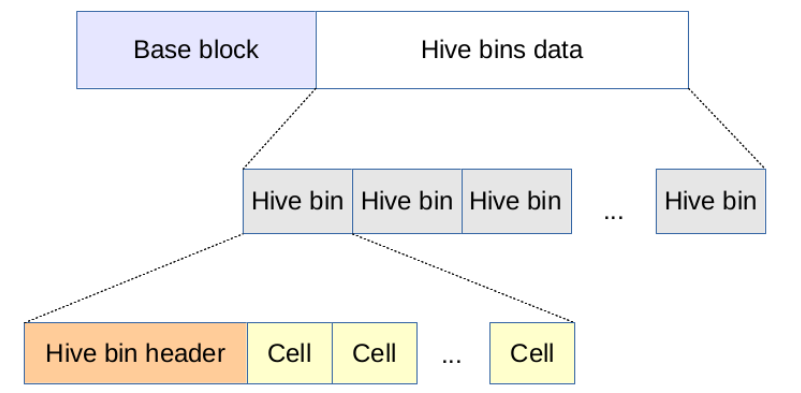

Next let us take a quick look inside the primary file. The first concept one should learn about is block, which can be thought of as an allocation unit and is always 4Kb in size. Should the primary file be extended to accommodate more data the space will always be allocated in multiples of the block size. At the very beginning of the file is a so-called base block. Base block contains what essentially is a hive header and provides all sort of useful information including, notably, hive sequence numbers.

The registry data itself – a hierarchy of keys and associated values – are stored in cells. Each cell holds one of the following: a key, list of subkeys, list of values, value, or security descriptor. Recent versions of Windows introduced a new feature called “layered keys”, but since the HKLM\SOFTWARE hive does not seem to support them yet, we will not discuss the subject here.

The keys hierarchy is constructed by means of cell indexes whereby a cell index is defined as an offset of the cell into the primary file starting from the first byte that follows the base block. Thus, a cell of a parent key contains an index of a “list of subkeys” cell (which, internally, is nothing more than a sequence of subkeys’ cell indexes) and, what will turn out to be of particular interest to us, a cell of each subkey holds a cell index of its parent.

When a new cell is appended to the hive, a container that would hold it, a so-called bin, is created. The unoccupied space between the end of the cell and the end of the bin (possibly of nonzero size because of the block-granular allocations) is considered free and in the future may be allotted to another cell (provided the cell is small enough to fit therein). The figure below (borrowed from Maxim Suhanov’s Windows registry file format specification illustrates the structure that has just been described.

When a key or a value is deleted, the underlying cell is freed and combined with adjacent free cells, if any. Adjacent free bins may also be joined together to increase the size of available free space and this is not the only space optimization employed by Windows: additionally, hives are “reorganized” at regular intervals. The precise nature and periodicity of reorganization depends on the system settings, but by default, the primary file gets defragmented once every two weeks. The process of defragmentation is what you would expect it to be: it compacts the data thereby removing all the unused space. One can figure out when a hive was last reorganized by consulting the Last Reorganized Timestamp field stored in the base block.

We’ve got all the information we need for now, but before moving on I would like to note that pretty much everything concerning Window registry that is known to me and, by extension, presented here I learned from either Windows Internals or Windows registry file format specification, the sources most insistently recommended for obtaining further information on the subject.

First Steps

For starters, let us look for one of the missing keys (say, HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\IniFileMapping) in the hive primary file for it stands to reason that even if the registry tree structure got damaged, the block containing IniFileMapping’s data might still have survived.

1

2

~$ strings /media/ubuntu/Data/WinRestore/RegBakup/SOFTWARE | grep IniFileMapping

IniFileMapping

The output looks promising thereby prompting further investigation.

1

2

~$ hexdump -C /media/ubuntu/Data/WinRestore/RegBakup/SOFTWARE | grep IniFileMapping

03608070 49 6e 69 46 69 6c 65 4d 61 70 70 69 6e 67 00 00 |IniFileMapping..|

Using key cell structure description from Maxim Suhanov’s documentation, it is easy to compute the offset where the encompassing “key node” cell begins.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

~$ hexdump -C -s 0x03608020 -n 112 /media/ubuntu/Data/WinRestore/RegBakup/SOFTWARE

03608020 a0 ff ff ff 6e 6b 20 00 94 46 09 cd e2 f7 d3 01 |....·nk· ..F......|

03608030 02 00 00 00 ·e8 c7 5f 03· 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |......_.........|

03608040 80 75 60 03 ff ff ff ff 00 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff |.u`.............|

03608050 78 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff 24 00 a0 00 00 00 00 00 |x.......$.......|

03608060 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0e 00 00 00 |................|

03608070 49 6e 69 46 69 6c 65 4d 61 70 70 69 6e 67 00 00 |·IniFileMapping·..|

03608080 a0 ff ff ff 6e 6b 20 00 94 46 09 cd e2 f7 d3 01 |....nk ..F......|

03608090

Please, observe the “nk” signature that identifies cell’s type (so we are on the right track) and a cell index of this key’s parent. Given the latter and the size of base block (4096 bytes), one can compute an offset for the parent cell as follows: 0x035fc7e8 + 4096 = 0x35FD7E8. The parent cell is examined in exactly the same manner and this procedure is repeated until the root key is reached; by this simple (though rather tedious) process a complete path to the subkey can be obtained.

To my dismay, it turned out to be WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\IniFileMapping, a reflection of the original key for use by 32-bit applications that were running on 64-bit platforms. Not only did it not contain enough information to recover all the missing data, for some mysterious reason, subkey sets of WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion and Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion were mutually exclusive. Look!

1

2

3

4

>>> s1 = set([ sk.name() for sk in reg_brk.open("Microsoft\\Windows NT\\CurrentVersion").subkeys() ])

>>> s2 = set([ sk.name() for sk in reg_brk.open("WOW6432Node\\Microsoft\\Windows NT\\CurrentVersion").subkeys() ])

>>> s1.intersection(s2)

set()

Quite inexplicable, I found it. At any rate, this simple experiment obviated the necessity of looking for that inconspicuous little nook on the breadths of my hard drive where the registry data might have been retained or backed up. The first place to look was the set of transaction log files; however, feeding the said logs to the registry-transaction-logs utility from Martin Korman’s Regipy package produced no improvement. For a brief moment, I considered examining the NTFS’s $BitMap in order to find clusters that were freed but not yet overwritten or leveraging journaling capabilities of the file system to try and undo the modifications that led to the data loss, but then a better idea came to mind. I recalled that I had Volume Shadow Copy Service enabled!

VSS to the Rescue!

Volume Shadow Snapshots (VSS) is a built-in OS technology that enables Windows to create copies (snapshots) of entire hard drive volumes; unless disabled, it is done automatically at regular intervals and every time the system is about to undergo significant changes (e.g. installing an update). By default, shadow copies are handled by the volsnap.sys driver and a copy-on-write (also known as differential copy) technique is used. It works as follows.

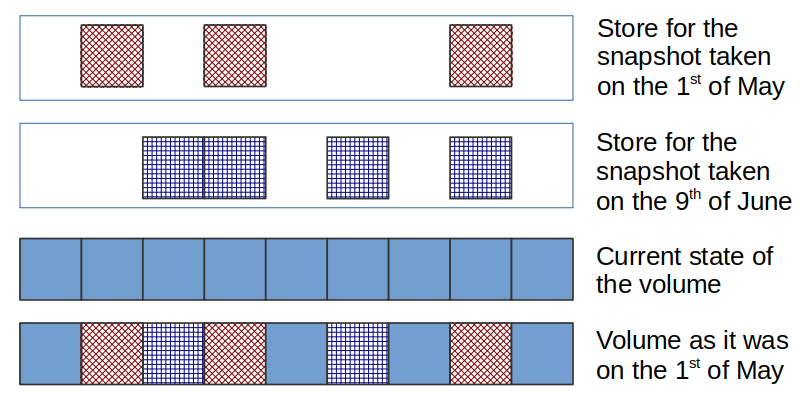

Shadow copies are stored each in the form of a single binary file (called “store”) that resides in the System Volume Information directory and adheres to the <store GUID>{3808876b-c176-4e48-b7ae-04046e6cc752} naming pattern. Every time a volume snapshot is requested, a store to hold it is created, but no data is copied at this point. Volsnap, being a “storage filter”-type driver, sits on top of the file system driver and monitors all the write operations. The volume is divided into units of identical length. As to the exact nature of these units, there seem to be a discrepancy in the literature: Joachim Metz writes about 16Kb blocks whereas in Windows Internals the copy-on-write mechanism is described in terms of hard drive sectors. Perhaps, using the generic term “block” would be appropriate in this case and, without loss of generality, this is what we will call a stretch of continuous disk space of minimum size that is handled by VSS, whatever it may be.

Whenever a block is about to be modified (by a “write” call to NTFS driver), volsnap makes a copy of it and stores the copied “old” block in a “differential area”, i.e in a store for the active snapshot. This way, stored are only those blocks that have changed since the time the snapshot was taken.

Such an organization, while efficient in terms of storage amount used, is not resistant to errors. For one, in order to reconstruct the state of the volume at the time a snapshot was taken volsnap needs all the snapshots taken afterwards in addition to the current data on that volume. For example, let there be two snapshots, one taken on the 1st of May and another – on the 9th of June, in the system; the figure below shows the blocks involved in the reconstruction of the volume as it was on the 1st of May.

Should data in any of the two stores or current state of the volume be lost, the snapshot will not be recoverable. Additionally, normal operation of the copy-on-write mechanism is sustained assuming that all the modifications to the file system are made by the Windows storage stack, a stack of drivers that every read/write request passes through. What if a volume gets written to by something other than the instance of Windows OS hosting Volume Shadow Copy Service, say, by another operating system booted from a flash drive? All the shadow copies on the said volume may end up broken.

Keeping everything just said in mind and our expectations low, let us check out the shadow copies supposedly present on the system volume. There are a few options available, when it comes to extracting data from VSS stores under Linux: dfir_ntfs (NTFS parser with shadow copies support by Maxim Suhanov), libvshadow (VSS format parser by Joachim Metz), and digital forensics and incidence response kits with VSS support. Of these, I tried libvshadow only so this is what we are going to use.

NOTE:

Since libvshadow enables its users to retrieve the files residing on a shadow copy with the help of FUSE, software (and, in particular, a library) that provides an interface for creating file systems in user space, we begin by installing libfuse: sudo apt install libfuse-dev.

Here is how one extracts HKLM\SOFTWARE hive from the latest shadow copy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

~$ sudo vshadowmount /dev/sda5 ~/mnt/fuse

~$ sudo ls -l ~/mnt/fuse

total 0

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss1

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss10

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss11

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss12

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss13

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss14

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss15

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss2

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss3

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss4

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss5

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss6

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss7

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss8

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 957292216320 Nov 17 14:37 vss9

~$ sudo mount -o loop,ro /home/ubuntu/mnt/fuse/vss15 ~/mnt/file_system

~$ cp ~/mnt/file_system/Windows/System32/config/SOFTWARE ~/RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE

~$ cp ~/mnt/file_system/Windows/System32/config/SOFTWARE.LOG1 ~/RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE.LOG1

~$ cp ~/mnt/file_system/Windows/System32/config/SOFTWARE.LOG2 ~/RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE.LOG2

There are 15 shadow copies in total found on my Windows system hard drive with vss15 being the latest one and the one, it stands to reason, we should use. However, attempting to query HKLM\SOFTWARE exposes a little problem. The registry is corrupt!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

>>> reg = Registry("RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE")

>>> cv = reg_brk.open("Microsoft\\Windows NT\\CurrentVersion")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.8/dist-packages/Registry/Registry.py", line 442, in open

return RegistryKey(self._regf.first_key()).find_key(path)

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.8/dist-packages/Registry/Registry.py", line 357, in find_key

return self.subkey(immediate).find_key(future)

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.8/dist-packages/Registry/Registry.py", line 357, in find_key

return self.subkey(immediate).find_key(future)

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.8/dist-packages/Registry/Registry.py", line 316, in subkey

for k in self._nkrecord.subkey_list().keys():

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.8/dist-packages/Registry/RegistryParse.py", line 1377, in keys

yield NKRecord(self._buf, d.data_offset(), self)

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.8/dist-packages/Registry/RegistryParse.py", line 1480, in __init__

raise ParseException("Invalid NK Record ID")

Registry.RegistryParse.ParseException: Registry Parse Exception (Invalid NK Record ID)

>>>

So the registry hive is corrupted, which should not have come as a surprise. As it has already been mentioned, in the default implementation shadow copies are stored as deltas between the state of the volume at the time the snapshot was taken and its current state, hence modifications to the hard drive outside normal Window’s operation may render existing shadow copies invalid. Devout readers will have recalled that it was a boot-time utility that got the system into an unbootable state (less faithful readers, I hope you are appreciating the thrill of unfamiliar). I made the situation worse by trying out recovery tools and experimenting with registry settings from an instance of WinRE. Had I taken my own advice and made an image of my hard drive (or, at least, of the system partition) before running any of the recovery-related experiments the situation would, most likely, have been slightly better. Alas! I had no space to store the partition image. Nevertheless, let us see what can be salvaged from this broken shadow copy.

The Scavenger Hunt

We begin with some basic diagnostics. Let us first make sure there are no errors in the hive’s header and then compare the sequence numbers on the off chance that the the snapshot has been taken mid-way through the hive update, and thus the registry can possibly be recovered from the transaction logs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

>>> reg = Registry("RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE")

>>> reg._regf.validate_checksum()

True

>>> reg._regf.hive_sequence1()

911625

>>> reg._regf.hive_sequence2()

911625

No such luck! Some other recovery strategy is in order, so here is the plan. Recall that all bin allocations within hive are block-granular meaning that bins are always placed at block boundaries (i.e. they are block-aligned). Our algorithm will read (and parse) the hive block by block (instead of enumerating nodes in its hierarchical structure) and, upon encountering a parsing error, will start skipping 4Kb-long chunks of data until a block with “hbin” signature in its first four bytes is encountered, then resume parsing from there. This method may potentially generate orphaned subkeys and values (when the hive contains damaged “list of subkeys” or “list of values” cells), but, since each subkey keeps an index of its parent, the key-subkeys hierarchy may, at least partially, be restored; orphaned values, on the other hand, we cannot do anything about – they will be collected for informational purposes only.

Python-registry library (ver. 1.3.1) by Willi Ballenthin will be used as a basis for our implementation. In order to iterate over the blocks in search of the next valid bin (in a manner, as pain-free as possible), we must modify the the library itself:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

class HBINBlock(RegistryBlock):

#[...]

def has_next(self):

"""

Does another HBINBlock exist after this one?

"""

regf = self.first_hbin().parent()

if regf.hbins_size() + regf.first_hbin_offset() == self._offset_next_hbin:

return False

#Looping over blocks until a valid bin is found

while self._offset_next_hbin < len(self._buf):

try:

self.next()

return True

except (ParseException, struct.error): #skipping the damaged block

self._offset_next_hbin += 0x1000 #each block is 4Kb in size

return False

With this little adjustment in place, we can now write a python script that would read the hive block by block while assembling the key/values hierarchy. The functionality is divided among three classes: BrokenRegistry, BrokenKey, and BrokenValue. The main purpose of the latter two is to keep track of the parent/container for the corresponding key/value. BrokenRegistry is the class that attempts to load a corrupt registry; among its methods is _load_broken() that does the job.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

class BrokenRegistry:

#[...]

def _load_broken(self, reg):

for hb in reg._regf.hbins():

for cl in hb.cells():

if cl.is_free():

continue

cell = cl.child()

if isinstance(cell, VKRecord):

#Omitted: creating an instance of BrokenValue

pass

elif isinstance(cell, NKRecord):

#Omitted: creating an instance of BrokenKey

pass

I am not going over the entire script here because, for the most part, it is tedious and mind-numbingly dull, but anyone interested in the details is more than welcome to peruse the complete version.

Now let us try and load the recovered HKLM\SOFTWARE registry hive.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

>>> reg = load_registry("RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE", verbose = True, normal_load = False)

Data type 0x4f6 Unknown type: 0x4f6 is not implemented

RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE -- orphaned keys:

ROOT

5222821f-d5e2-4885-84f1-5f6185a0ec41

880fd55e-43b9-11e0-b1a8-cf4edfd72085

D09BDEB5-6171-4A34-BFE2-06FA82652568:fdd099c6-df06-4904-83b4-a87a27903c70

a111f1c5-5923-47c0-9a68-d0bafb577901

30034843-029d-46ec-8fff-5d12987f85c4

2d24ff0b-1bab-404c-a0fd-42c85577bf68

7642249B-84C2-4404-B6EB-1E0A2458839A

[...]

RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE -- orphaned values:

DxDebugEngine.resources,fileVersion="14.0.25420.1",version="14.0.0.00000",culture="ko",publicKeyToken="null",processorArchitecture="MSIL"

VsGraphicsStandalonePkg.resources,fileVersion="14.0.25420.1",version="14.0.0.00000",culture="ja",publicKeyToken="B03F5F7F11D50A3A",processorArchitecture="MSIL"

Comm

Fing

Free

Fam

Mic

OEM

Office

Paper

Perf

Complete

1_PlannedTimeLow

[...]

I had to cut down the output considerably in order to preserve readability, but here is some statistics collected while loading the hive: 18322 blocks were skipped in the process, the resulting key/value hierarchy contained, apart from the invariably parentless ROOT key, 480 orphaned keys (i.e. keys with parent indexes pointing to non-existent or damaged entries) and 1199 orphaned values. The file turned out to be severely damaged, with large chunks of data replaced by garbage. For comparison: in a healthy hive (spoiler alert! In the end I did manage to recover one), there were 32972 bins, whereas in the damaged one roughly half of that – 16837.

1

2

3

4

>>> s = open("RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE", "rb").read()

>>> s.count(bytes('hbin', 'utf-8'))

16836

>>>

What is more, the notorious Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion key is missing altogether from the hive.

1

2

3

>>> reg = load_registry("RecReg_vss15/SOFTWARE", verbose = False, normal_load = False)

>>> print(reg.find_path("ROOT\\Microsoft\\CurrentVersion"))

None

Obviously, it is a no-go.

Wines Shadow Copies Only Get Better with Time

Well, only some shadow copies do; quite possibly, this is the only case in history where an older shadow copy proved to be (almost) error-free while the most recent one did not.

Given that we are dealing with the differential “copy-on-write” technique (where preceding copies are constructed from their successors) and the most recent file is in shreds and tatters, is it worth checking the older shadow copies? It depends. In this case it did and here is why. As we already know, at regular intervals, primary registry files undergo a process of reorganization during which layout of the file may change to such a degree that it will no longer occupy the same set of hard drive sectors, hence there is a chance that the older copy of the registry does not overlap the damaged region of storage space. The exact time when the last reorganization was performed can be established by consulting the “last reorganized timestamp” field stored in hive’s base block so the plan goes as follows: proceeding backwards in time, check each shadow copy of the HKLM\SOFTWARE hive such that its reorganization timestamp differs from that of the last copy checked and see how many orphaned keys and values it contains. The goal is to find a relatively recent copy with minimum orphans.

I will not bore you, my ever-patient reader, with a step-by-step account of the procedure, but I think I found the perfect candidate: the hive copy is located in vss8, it is not too old and contains no orphans. No orphans.

Of course, it would have been immensely interesting to check my hypothesis as to how this hive copy managed to emerge unscathed from the perils of dealing with boot-time utilities. It could have been accomplished by examining how many and which hard drive sectors vss8 and vss15 had in common had I done so right away. Unfortunately, I did not create a “byte-by-byte” backup copy of the volume and, since it had been months before I brought myself to finish this write-up, the shadow copies were long gone by then. At least, let us assess the quality of our find.

| vss8 | vss15 | |

| print(reg._regf.modification_timestamp()) | 1601-01-01 00:00:00 | 1601-01-01 00:00:00 |

| reg._regf.hive_sequence1() | 899494 | 911625 |

| reg._regf.hive_sequence2() | 899494 | 911625 |

| print(reg._regf.reorganized_timestamp()) | 2018-10-23 14:12:37 | 2018-10-30 21:01:20 |

As far as the dual-logging scheme goes, the vss8 hive is in a consistent state and, overall, it appears to be error-free, with the exception of warnings about data of unknown types, the types identified by the magic numbers 0xd, 0x11, 0x12. The latter is of no great concern for all the values with unknown types reside in \Microsoft\Device Association Framework\Store\ subkey and seem to be associated with Bluetooth devices paired with my laptop. I can reestablish the pairings anytime.

Nowadays Windows keeps track of modifications on per-key basis while the field Global Last Modified Timestamp remains uninitialized. Still, the reorganization timestamp gives us a rough idea of how old the hive in question is (to be more precise, the higher boundary for its age). The incident leading to creation of the Abyss series took place on the 7th of November, 2018 and vss8 copy of the hive was reorganized on the 23rd of October, same year. Not too bad. However, substituting vss8 copy for the problematic hive is not feasible due to the fact that during the two weeks preceding the incident a number of important updates (of which there would remain no trace in the registry) were installed. One might suggest copying missing keys and values from the current hive to the vss8 copy as a viable solution and this is precisely what I was going to do. Alas! The treacherous system had one more surprise in store for me.

The Mysterious Hive

NOTE: Although the last statement might have come across as theatrical and, certainly, more dramatic than it was called for, there is something unusual about the unbootable system’s registry.

Trying to bring the said plan to fruition, I set to analyze the keys from the current registry on the unbootable laptop that were absent in the vss8 shadow copy and, for that reason, presumed to be added after the 23rd of December (after all, it was advisable to determine how profound the changes introduced by the latest updates were). Among them, there were keys with modification timestamps earlier (sometimes as early as six months before) than the vss8 copy’s reorganization timestamp. Here is one I chanced upon.

1

2

3

¡; Updated on the 2018-04-11 23:39:25.521896¡

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\·{17E68D04-5A63-4692-A2BF-7571F31AC130}·\ProgID]

"@"="·VSMGMT.VssSnapshotMgmt.1·"

The information on {17E68D04-5A63-4692-A2BF-7571F31AC130} vss8 copy gives us is as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

¡; Updated on the 2018-05-30 06:57:32.190956¡

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\·{17E68D04-5A63-4692-A2BF-7571F31AC130}·]

"@"="AutomaticDisplayBrightness Class"

"AppID"="{A4F75D5C-55DF-4556-B27F-F4B8C17EE920}"

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{17E68D04-5A63-4692-A2BF-7571F31AC130}\Programmable]

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{17E68D04-5A63-4692-A2BF-7571F31AC130}\TypeLib]

"@"="{B9B176D4-052F-40AB-95C3-5DFE502AFE47}"

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{17E68D04-5A63-4692-A2BF-7571F31AC130}\Version]

"@"="1.0"

COM classes identified by the same guid in the vss8 copy and the current registry seem to be unrelated. What is more, in vss8 VSMGMT.VssSnapshotMgmt.1 is associated with a completely different CLSID:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\·{0B5A2C52-3EB9-470a-96E2-6C6D4570E40F}·]

@="VssSnapshotMgmt Class"

"AppID"="{56BE716B-2F76-4dfa-8702-67AE10044F0B}"

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\·{0B5A2C52-3EB9-470a-96E2-6C6D4570E40F}·\ProgID]

@="·VSMGMT.VssSnapshotMgmt.1·"

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\·{0B5A2C52-3EB9-470a-96E2-6C6D4570E40F}·\VersionIndependentProgID]

@="VSMGMT.VssSnapshotMgmt"

Below is another, more telling, example:

1

2

¡; Updated on the 2018-04-11 23:39:25.271875¡

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{2559a1f0-21d7-11d4-bdaf-00c04f60b9f0}\·{0DE86A57-2BAA-11CF-A229-00AA003D7352}·]

Well, guid CATID_PersistsToPropertyBag = {0DE86A57-2BAA-11CF-A229-00AA003D7352} identifies a COM category and it is usually linked to its parent component via the Implemented Categories subkey like this:

1

2

3

¡;legitimate key example¡

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{1DF7D126-4050-47F0-A7CF-4C4CA9241333}\·Implemented Categories·\·{0DE86A57-2BAA-11CF-A229-00AA003D7352}·]

@=hex(0):

As is the hive it completely unusable. Yet, despite all these “semantic” errors, structure- or syntax-wise the hive is sound: no registry-parsing library or application (including regedit32) found anything wrong with it. It would appear that some frankenstein of a software, having found the registry in total disarray, put its remains back together in a semi-random fashion with the result taking shape of a hive’oid in the Registry world. I have no idea who the creator was, but can offer a hypothesis. Consider this quote from Windows Internals by Alex Ionescu, David Solomon, and Mark Russinovish.

The Windows Boot Loader also contains some code related to registry reliability. For example, it can parse the System.log file before the kernel is loaded and do repairs to fix inconsistency. Additionally, in certain cases of hive corruption (such as if a base block, bin, or cell contains data that fails consistency checks), the configuration manager can reinitialize corrupted data structures, possibly deleting subkeys in the process, and continue normal operation.

Here is another quote from the same source:

The first block of a hive is the base block. It includes […] information on registry repair and recovery preformed by Winload.

On the other hand, the corrections done by the boot loader and configuration manager might be strictly “in-memory” as implicitly suggested by Maxim Suhanov’s documentation:

The Boot type and Boot recover fields are used for in-memory hive recovery management by a boot loader and a kernel, they are not written to a disk in most cases (when Clustering factor is 8, these fields may be written to a disk, but they have no meaning there).

In short, the literature review is inconclusive :-). Sfc.exe is another possible candidate. I guess, at this point we will never know, but one thing is clear: since the HKLM\SOFTWARE hive on the unbootable system contains phony data, we cannot simply copy the missing keys and values from there to the “clean” (but outdated) registry stored as a part of the vss8 shadow copy.

The Chosen Registry Recovery Technique

To recap, listed below are versions of HKLM\SOFWARE hive we managed (with considerable effort) to procure:

- vss8 shadow copy which is error-free, but outdated.

- vss15 shadow copy, a severely damaged copy with half of the keys and values missing (the retained keys and values, however, we can trust); it is newer, but still somewhat outdated.

- current and the most recent version of the hive; it contains bogus keys that should not be there.

We will call them input hive, and primary and supplementary sources of patches respectively; then the proposed algorithm for hive recovery goes as follows:

- Remove all the values of unknown type from the input hive (an optional step that will simplify troubleshooting in case Windows rejects the generated hive).

- From the primary source of patches, extract keys and values such that their counterparts-“pathsakes” are not present in the input hive.

- Enumerating all the entries in the list obtained in step 2, check if there is a newer version of the key or value in the supplementary source of patches and, if found, substitute it for the older entry. Modification timestamps for the values are taken to be that of the encompassing keys.

- Remove all the keys named “SessionsPending” from the list. These are the artifacts of past installation sequences.

- The list entries are exported in Windows Registry Editor format and then combined into a single .reg file which, in turn, is imported into the input hive using regedit32.

- The resulting input hive replaces HKLM\SOFTWARE hive on the unbootable system.

Notice that only the keys already present in the vss8 copy are considered in step 3, hence no invalid data from the current registry can make its way into the new “clean” hive.

This algorithm is implemented in a form of a python script that can be found here. In this script, there are classes AddKeyMod, AddValueMod, ChangeValueMod, DeleteValueMod that represent various modifications to the registry and a function called bring_up_to_standard() that generates the said modifications while attempting the “equalize” data in two hives (see step 2).

This technique is far from ideal for reasons so numerous that one does not know whence to begin. For one, all the keys and values Windows removed since the time vss8 copy was modified last will be retained. Then, a number of registry entries added between that time and the vss15’s modification timestamp may be lost due to vss15 copy being severely damaged, not to mention the data added after vss15 snapshot was taken.

The imperfections were too many to count, but, nevertheless, it was worth trying before coming up with a more complicated algorithm. And it worked! Never in my life was I this happy to see Windows’ logon screen!

All that remained to be done was “poking around” various system services and installed applications for the purpose of making sure everything ran correctly, but the OS had something else in mind. In horror, I watched Windows eagerly plunge into its favorite occupation – updating itself – as installing updates unto unstable system could have rendered it unbootable once again. It did not happen and I am glad to report that no registry-related errors have been encountered after that fix.

Conclusion

We have come a long way in our understanding of the problem on our hands from the vague “Your PC ran into a problem and needs to restart. Stop code: CRITICAL_PROCESS_DIED.” BSOD message. The first step presented no challenge at all: simple bugcheck analysis gave us the name of the deceased: csrss.exe, but thence the road lying before us proved more demanding. Struggling through the tangles and knots of traces left on the stack by system calls, we reached the exact location where the error code was stored and, after that, keeping our eyes pealed for the execution artifacts in memory, we analyzed csrss’ initialization procedure instruction by instruction so as to identify the offending function. ServerDllInitialization() from basesrv.dll turned out to be our culprit. Then came the long nights of ceaseless and tireless reverse-engineering with many lonely hours spent by blue-saturated LED candlelight. Eventually, pristine wholesome-looking C-code emerged illuminating the dark forces behind blue screens of death and we could clearly see the only system call that could have possibly returned the error code, NtOpenKey(). Thus, the glorious name of basesrv.dll was cleared and the real villain stood before us – a corrupt HKLM\SOFTWARE hive, a monster of the Registry world. And so we embarked on a quest to the land of Shadow Copies in search of a righteous SOFTWARE hive, but none could we find. Remains of great hives, dust and bone, were collected to conjure up the One and Only Illustrious Spirit of True Registry, that is to say, we had to combine data from multiple incomplete shadow copies of the hive in order to obtain a version that would work. Finally, the evil spell was broken and Window came back to life. If this heck of a journey does not feel like an odyssey to you I do not know what else could impress you, my battle-scarred reader.

In short, the entire exercise at diagnostics took an awful lot of time; I went to great lengths to figure out what the problem actually was and am bored stiff reiterating (over and over again) the steps it took to get there every time a need to put something together for an introduction or conclusion in this never-ending multipart series arises.

All jokes aside, was the result worth all this effort and time it took? In all honesty, simply reinstalling the system along with all the software therein would have been a lot less energy- and time-consuming. Negligible, however, would have been the contribution of said enterprise to the enlightenment of mankind and, more importantly, my emotional well-being (for the entertaining aspect of an intricate puzzle and the satisfaction brought by achieving its solution are hard to match).

What is so “enlightening” that I have learned? First of all, in many cases one does not require another full-fledged Windows instance to figure out why their OS would not work: thanks to a plethora of open-source utilities and libraries a Linux live CD coupled with WinRE would suffice. In other words, you do not need Windows to troubleshoot Windows. Second of all, the existing troubleshooting techniques typically recommended in the situations similar to mine are meant to be applied blindly, without identifying the exact cause of the issue on one’s hands first. The user in trouble is simply suggested to throw everything but the kitchen sink at their OS and see what works. The need for tools that would give some insight into “inner workings” of a crash without the hassle of debugging/tracing and reverse-engineering by hand, therefore, becomes apparent. Finally, more often than not, once their system becomes unbootable, people are advised to give up and make a clean install as I, surely, would have been told to do had I actually asked. Just look through the tech support forums. But the data necessary to restore the system was still there, relatively intact, lying hidden in the depths of my hard drive, waiting for a person with right tools and a great deal of perseverance to show up. When something can be done in principle, quite often it can be done in practice, too. People who have grown particulary fond of their OS setups should not get disheartened for, with enough effort put in, they are likely to get their systems back. ;-)

Epilogue

By now the reader, probably, wants to know the name of that vicious boot-time utility that breaks innocent operating systems. No need for righteous indignation. Here is it is. My laptop manufacturer provides its users with the functionality of either resetting the computer to its factory default state or restoring the OS to a previously created back-up point, both performed by a utility that is accessible via a boot menu item. This menu item is what I accidentally tapped on one coffee-less morning. The recovery environment, activated as a result, promptly started collecting information necessary to restore the system (or so it claimed) and in this state it was stuck for what seemed like eternity. Being in a hurry, I decided to regain the much needed access to my laptop by a cold reset. “It is just collecting data at this point. What could possibly go wrong?”, I thought. Well, evidently, the recovery environment was using my hard drive to store the data being collected for upon reset Windows decided to launch a copy of chkdsk. Chkdsk did not find any problems apart for a few orphaned prefetch files, so there was no sign of trouble, but then Windows refused to boot. And this is how it all began.

– Ry Auscitte

References:

- René Nyffenegger, Registry: HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion

- Willi Ballenthin, python-registry: Pure Python parser for Windows Registry hives

- The system registry is no longer backed up to the RegBack folder starting in Windows 10 version 1803 – Microsoft Docs

- Maxim Suhanov, Windows registry file format specification

- Ry Auscitte, Bringing My OS Back from the Abyss: Windows Crash Dump Analysis (Part 1)

- Ry Auscitte, Bringing My OS Back from the Abyss: Reversing basesrv.dll Initialization Procedure (Part 2)

- Mark E. Russinovich, David A. Solomon, and Alex Ionescu. 2012. Windows Internals, Part 1: Covering Windows Server 2008 R2 and Windows 7 (6th. ed.). Microsoft Press, USA.

- Registry Hives – Microsoft Docs

- Joachim Metz, Windowless Shadow Snapshots: Analyzing Volume Shadow Snapshots (VSS) without using Windows, OSDFC 2012

- Maxim Suhanov, dfir_ntfs: An NTFS parser for digital forensics & incident response

- Joachim Metz, libvshadow: Library and tools to access the Volume Shadow Snapshot (VSS) format

- Martin Korman, Regipy: An OS Independent Python Library for Parsing Offline Registry Hives