Bringing My OS Back from the Abyss : Reversing basesrv.dll Initialization Procedure (Part 2)

WARNING: The work presented in this post was done before the Rizin fork of radare2.

Assuming that you, my faithful reader, have clicked on the “part 2” link without even a moment of hesitation or delay, immediately upon completing the first installment, and all the information provided therein is still fresh in your memory, I will omit lengthy introductions and cut straight to the chase.

So let us pick up where we left off… In part 1 we identified a call to the ServerDllInitialization routine from module basesrv.dll as the one resulting in an error (and thereby causing csrss, a Windows critical process, to terminate). One possible course of action at this point is to delve into the inner workings of the routine with the intention of determining what caused the error. This is precisely what we are about to do. To this end, we will look for patterns:

1

2

3

ret_code = winapi_call(...);

if (FAILED(ret_code))

return ret_code;

and, among them, system calls that potentially may return STATUS_OBJECT_NAME_NOT_FOUND.

An Attempt at Automatic Decompilation

Given the ServerDllInitialization function’s formidable length of nearly 4 kilobytes, working with code in some high-level language appeared substantially more convenient than fishing for heads and tails in an endless stream of assembly instructions. Unfortunately, cdb did not come equipped with a decompiler hence it was time to check if the benevolent world of open-source had something to offer; and to nobody’s surprise, they had. Right off the bat, I discovered three tools able to understand Windows PE format and translate assembler instructions into C-like pseudo-code: NSA’s ghidra, Avast’s retdec, and radare2 (quite likely, there are more). Radare2 with its built-in decompiler and a sizable selection of third-party plugins, including, notably, r2ghidra-dec and retdec-r2plugin, that ported the functionality of their namesake decompilers, seemed like it would allow to kill all the birds with one stone so it was the framework I had chosen.

NOTE: Here I should point out that these were imaginary, inanimate, “figurative” birds; “no birds were harmed in the course of this reverse engineering endeavor”, one feels compelled to add to avoid sounding disturbingly barbaric these days.

As an [actual] side note, to save the trouble we, of course, could limit our efforts to analyzing React OS code, but this decision puts us on a dangerous path. As I already warned, caution must be exercised when using React OS source code in place of the actual disassembled Windows binaries for one cannot expect exact imitation of system’s behavior. In our case React OS has been designed to be compatible with a different version of Windows and, thus, in the same setting in may behave differently. It may not even crash! Still, we will use it for reference.

Meet The Subject

Why not begin with a bit of information on the basesrv.dll module so we all know what we are working with?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ rabin2 -I basesrv.dll

arch x86

baddr 0x180000000

bits 64

dbg_file basesrv.pdb

lang c

machine AMD 64

It is a 64-bit module compiled from C sources with its preferred base address set to 0x180000000; however, the flag IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_DYNAMIC_BASE = 0x0040 (see below) tells us that the module can potentially be loaded at a different address (which will be of concern only if csrss.exe is debugged / disassembled and not basesrv.dll by itself).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Python 3.8.5 (default, Jul 28 2020, 12:59:40)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import pefile

>>> pe = pefile.PE("basesrv.dll")

>>> hex(pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.DllCharacteristics & 0x0040)

'0x40'

Another relevant to the problem in hand piece of information is the import table.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

>>> pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT[0].dll

b'ntdll.dll'

>>> names = [ itm.name for itm in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT[0].imports ]

>>> for k in range(len(names) // 4):

... print(*names[k*4 : k*4 + 4], sep = " ")

... print(*names[4 * (len(names) // 4) : 4 * (len(names) // 4) +\

... len(names) % 4 ], sep=" ")

...

b'swprintf_s' b'_vsnwprintf' b'RtlAllocateHeap' b'NtQuerySystemInformation'

b'RtlQueryRegistryValuesEx' b'wcsncpy_s' b'RtlInitUnicodeStringEx' b'NtOpenKey'

b'NtQueryValueKey' b'_wcsicmp' b'NtClose' b'RtlCreateSecurityDescriptor'

b'RtlSetDaclSecurityDescriptor' b'RtlSetSaclSecurityDescriptor' b'NtCreateDirectoryObject' b'NtSetInformationObject'

b'NtCreateSymbolicLinkObject' b'NtQueryInformationProcess' b'RtlInitializeCriticalSectionAndSpinCount' b'RtlAppendUnicodeToString'

b'RtlAppendUnicodeStringToString' b'NtCreateFile' b'RtlFreeHeap' b'RtlDeleteCriticalSection'

b'RtlEnterCriticalSection' b'RtlUpcaseUnicodeChar' b'_snwprintf_s' b'NtOpenSymbolicLinkObject'

b'wcsnlen' b'memmove' b'NtQuerySymbolicLinkObject' b'NtMakeTemporaryObject'

b'_wcsnicmp' b'RtlAllocateAndInitializeSid' b'RtlFreeSid' b'RtlCreateAcl'

b'RtlAddAccessAllowedAce' b'NtMakePermanentObject' b'RtlCopyLuid' b'RtlLeaveCriticalSection'

b'RtlLengthSid' b'RtlAddAccessAllowedAceEx' b'RtlAddMandatoryAce' b'RtlAcquireSRWLockExclusive'

b'LdrGetDllHandle' b'RtlInitString' b'LdrGetProcedureAddress' b'RtlReleaseSRWLockExclusive'

b'wcscpy_s' b'RtlPrefixUnicodeString' b'NtQueryInformationToken' b'RtlCreateUserThread'

b'RtlExitUserThread' b'LdrLoadDll' b'LdrUnloadDll' b'NtOpenProcessToken'

b'NtDuplicateToken' b'NtSetInformationThread' b'NtSetInformationProcess' b'NtOpenProcess'

b'NtOpenThread' b'NtDuplicateObject' b'RtlCopyUnicodeString' b'NtSetEvent'

b'RtlCompareUnicodeString' b'RtlCreateProcessParametersEx' b'NtCreateUserProcess' b'RtlDestroyProcessParameters'

b'RtlAppendStringToString' b'NtResumeThread' b'NtWaitForSingleObject' b'RtlInitAnsiString'

b'RtlAnsiStringToUnicodeString' b'NtResetEvent' b'NtCompareTokens' b'NtOpenThreadToken'

b'NtCreateEvent' b'DbgPrint' b'RtlEqualSid' b'NtVdmControl'

b'NtCreateKey' b'NtNotifyChangeKey' b'RtlCopySid' b'NtEnumerateKey'

b'RtlEqualUnicodeString' b'NtEnumerateValueKey' b'RtlLockHeap' b'RtlUnlockHeap'

b'RtlInitializeSidEx' b'RtlCheckTokenMembershipEx' b'LdrDisableThreadCalloutsForDll' b'NtTerminateProcess'

b'RtlCaptureContext' b'RtlLookupFunctionEntry' b'RtlVirtualUnwind' b'RtlUnhandledExceptionFilter'

b'memcpy' b'wcscat_s' b'RtlCreateUnicodeString' b'RtlExpandEnvironmentStrings_U'

b'RtlInitializeCriticalSection' b'RtlCreateTagHeap' b'RtlGetCurrentServiceSessionId' b'RtlInitUnicodeString'

b'RtlGetAce' b'NtQueryObject' b'__C_specific_handler' b'ZwCreateKey'

b'RtlIsMultiSessionSku' b'ZwQueryValueKey' b'RtlOpenCurrentUser' b'ZwClose’

b'ZwOpenKey' b'NtQueryMultipleValueKey' b'memset'

There are three types of functions imported from ntdll.dll that we should keep in mind: string operators (such as wcscat_s or wcsncpy_s), memory management (e.g. memset), and Windows Native API (Nt*, Rtl*, Zw*); of the latter, only some are documented, while many others have documented counterparts with the same prototypes (but slightly different names) and functionality. String handling and memory management functions match their namesakes from C runtime libraries (which might have been statically linked) and are well-known.

Many more bits of useful information are hidden in PE headers and one is actively encouraged to study the output of print(pe.dump_info()) command in order to gain insight into one’s reversee; in the meantime we are proceeding with the topic of decompilation.

Decompilers: Comparative Analysis and Outcome

Listed below are the outputs produced by several decompilers (though I added snowman to the mix, this is still not by any means an exhaustive list):

- basesrv::ServerDllInitialiation() by r2ghidra-dec (ghidra decompiler, came with Cutter)

- basesrv::ServerDllInitialiation() by r2dec (came with Cutter)

- basesrv::ServerDllInitialiation() by retdec-r2plugin (integrates retdec functionality into radare2)

- basesrv::ServerDllInitialiation() by a built-in decompiler (invoked using pdc command)

- basesrv::ServerDllInitialiation() by r2snow (snowman)

NOTE: Well, I am not completely correct in classifying the aforementioned tools as decompilers: for starters, none of the generated code will actually compile; then, the outcome ranges from nothing more than syntactic sugar for assembler to almost fully-fledged C programs (save some definitions, headers and other minor details). In fact, what I call a built-in decompiler officially goes by the name of “pseudo disassembler in C-like syntax”.

The code resulting from decompilation by these tools, none being perfect, varied greatly in style and quality with no good way of choosing the best candidate. It just goes to show that there is no generic algorithm for (or general consensus on, for that matter) recovering high-level language constructs from assembly code. Take the execution flow, for example. A long series of Windows Native API calls with subsequent return value checks (and, upon encountering an error, a ret instruction following the mandatory resource clean-up), not counting accompanying bells and whistles, constitutes the bare-bones of ServerDllInitialiation(). In order to represent this type of program organization, built-in decompiler, r2snow, and r2dec use the traditional “if + goto” combo, while r2ghidra-dec translates the same structure into nested iffs. Yet another solution is chosen by retdec-r2plugin: it consists in putting all the clean-up handling code into separate functions that are used in conjunctions with the error-checking if statements, with the end result of producing an easier-to-follow but slightly incorrect (macros should have been utilized instead) code.

Speaking of execution flow, I noticed a possible bug that could give some insight into decompilation internals (without actually having to consult the source code) as well as make one miss a good portion of the function being reversed. At some point in the course of ServerDllInitialization() disassembling/analysis a few blocks of code got missing. For instance, here is an output of radare2’s pdd command performing “recursive disassemble across the function graph”:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

[0x180001680]> pdr

Do you want to print 989 lines? (y/N) y

;-- rip:

┌ 3552: sym.BASESRV.dll_ServerDllInitialization (int64_t arg1);

│ ; var int64_t var_80h_2 @ rbp-0x80

│ ; var int64_t var_bp_78h @ rbp-0x78

[...]

│ 0x18000213c 8bd8 mov ebx, eax

│ 0x18000213e 85c0 test eax, eax

│ 0x180002140 0f88312e0000 js 0x180004f77

| ----------- true: 0x180004f77 false: 0x180002146

│ ; CODE XREF from sym.BASESRV.dll_ServerDllInitialization @ 0x180004f85

│ 0x180002323 8bc3 mov eax, ebx

| ----------- true: 0x180002325

│ ; CODE XREF from sym.BASESRV.dll_ServerDllInitialization @ 0x180004ec2

│ 0x180002325 4c8bac24200f. mov r13, qword [var_f20h]

│ 0x18000232d 488bbc24180f. mov rdi, qword [var_f18h]

│ 0x180002335 4c8bb424280f. mov r14, qword [var_f28h]

[...]

Notice that the assembly listing omits the chunk of instructions beginning at the address 0x180002146. Interestingly, the body of ServerDllInitialization() is fragmented with the instructions from other functions, BaseSrvInitializeIniFileMappings() and BaseSrvSaveIniFileMapping(), squeezed in between its code blocks which is often the case for Windows OS binaries (see this post for details). Look!

1

2

3

4

5

6

$ python3 pdb_list_code_blocks.py -p basesrv.pdb -m basesrv.dll -n ServerDllInitialization

Function start: 0x180001680

Function end: 0x1800023f2 ( length = 3442 )

Separated blocks of code:

Block start: 0x180004d06

Block end: 0x180004f8a ( length = 644 )

However, seeing that the omitted block lies withing the very first continuous region of ServerDllInitialization(), the fragmentation could not be the (sole) cause of the problem.

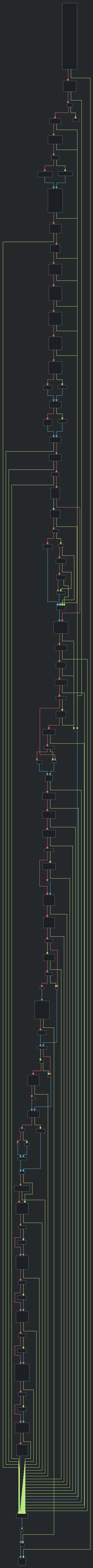

Pdd command as well as radare2’s (and Cutter’s) graph view, both, fell victim to this bug. It becomes apparent if you take a closer look at the bird’s eye view of control flow graph: the missing code contained two loops, one nested, but there are no edges going upwards on the screenshot. As for the decompilers, r2ghidra-dec, retdec-r2plugin, and r2snow seem to be immune to the issue, while the rest are affected by it. I suspect, whether this problem shows up or not depends on the internal representation the decompiler uses and, time permitting, it would be interesting to get to the core of the matter and check if my guess is correct. That said, radare2 and its plugins are in active development at present and, in all probability, this bug will have long been fixed by the time you stumble across this post on the vast stretches of the Internet. Nevertheless, it pays to be cautious and check twice.

The rest of discussion concerns implemented features rather than style. A convenient feature implemented by some (but not all) of decompilers is pulling constants from .rdata section and using their values explicitly in place of references (for example, wcscpy_s((int16_t *)&v12, 256, L"\\BaseNamedObjects");). In the setting of Windows codebase Unicode strings, thanks to their ubiquity, are of particular interest. Of the aforementioned decompilers, only r2dec, retdec-r2plugin, and, partly, built-in decompiler were capable of handling Unicode strings with the built-in decompiler placing the strings as commentaries alongside the assembly instructions referencing them.

Next in line are SSE instructions. It turns out, a subset of SSE instructions is extensively employed throughout the OS modules (mainly, for initialization purposes) and the segments of such code are not interpreted correctly, if interpreted at all, by decompilers. Mostly, SSE instructions are left “as is”, in __asm{} blocks / intrinsics, or simply ignored.

Another fundamental topic in decompilation is data type analysis. Basically, there are three methods of assigning a type to some memory location: by analyzing instructions operating on it, by inferring from function prototype (in case the data stored at this location is passed as an argument to a known or, in its turn, inferred function), and, finally, by reading some kind of meta-data that specifies the type explicitly (e.g. a symbol file). Obviously, one has to take into account “compound” sets of instructions where the value is first loaded into a register and only then operated on; then, some variables might not be stored in memory (stack or RAM) at all, but reside in registers only. In short, the topic is much more complex than I might have led you to believe.

This being the case, the variety in the quality and detailedness of type inference among various decompilers should not surprise us. All of the decompilers under consideration performed (to some degree) type analysis for local variables presenting the results either in the from of local variable declarations or statements such as “byte [rbx + 0x970] = r12b“ Decompilers r2ghidra-dec and r2snow stood out among the rest by walking one or two extra miles: r2ghidra-dec was able to compute array sizes (lengths of string buffers, to be more precise), while r2snow managed to deduce (partly) anonymous structures from the memory use patterns (which might come in handy given the extensive use of structures in Windows code). ServerDllInitialization() initializes fields of two structures whose counterparts in ReactOS code are called BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA and CSR_SERVER_DLL, not to mention SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR, that pops up every time the initialization routine needs a security descriptor. Of course, r2snow has no knowledge of what these structures are called in reality, so it unimaginatively names them s9, s55, and s60 respectively.

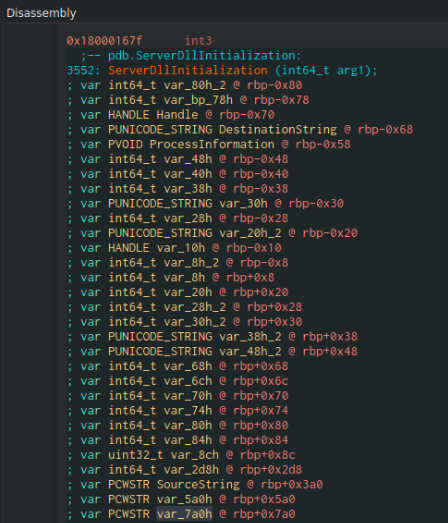

Having said all that, I would be a remiss not to mention the type information already available in the disassembly listings. Take a look at this Cutter screenshot.

Here are int64_t primitive types (appearing, no doubt, as a result of encountering “mov qword ptr” instructions) as well as PWCSTR and PUNICODE_STRING preceding informative (some of them) variable names such as SourceString (inferred from function prototypes). Thus, it is unclear how much of the type analysis is due to the decompilers themselves.

“What about global variables?”, you may ask. Well, you will not find declarations of global variables anywhere in the generated code, but r2dec, built-in decompiler, and r2ghidra-dec managed to give meaningful names for them by extracting appropriate symbols from pdb files. This is how it is done. Suppose, one is decompiling the following piece of assembly code:

1

2

3

4

mov edx,dword ptr [180010920h]

mov r8d,0B68h

mov rcx,qword ptr [180010918h]

call qword ptr [18000ca70h]

There are three instructions: two movs and a call – that reference memory addresses in this code snippet. Let us check if any of these addresses have symbols attached to them. For the purposes of demonstration we will use pbd_lookup utility. Presuming that basesrv.dll is loaded at its preferred base address, 0x180000000, the corresponding symbols are retrieved as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ pdb_lookup.py basesrv.pdb 0x180000000

Use lookup(addr) to resolve an address to its nearest symbol

>>> lookup(0x180010920)

'basesrv!BaseSrvSharedTag'

>>> lookup(0x180010918)

'basesrv!BaseSrvSharedHeap'

>>> lookup(0x18000ca70)

'basesrv!__imp_RtlAllocateHeap'

As a result, this instruction sequence translates into the function call:

1

RtlAllocateHeap(BaseSrvSharedHeap, BaseSrvSharedTag, 0x0B68);

Internally, pbd_lookup gets its data from a global symbols stream in the symbol file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Python 3.8.5 (default, Jul 28 2020, 12:59:40)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import pdbparse

>>> pdb = pdbparse.parse("basesrv.pdb")

>>> print(*[ s for s in pdb.STREAM_GSYM.globals\

... if "name" in dir(s) and "BaseSrvSharedHeap" in s.name ], sep="\n")

Container:

length = 30

leaf_type = 4366

symtype = 0

offset = 2328

segment = 3

name = u'BaseSrvSharedHeap' (total 17)

Yet another set of tasks decompilders occupy themselves with could be branded together under a (made-up) term “resolving a function call”; it encompasses procuring function name, retrieving or deducing function prototype (or, at least, the number of formal parameters), and figuring out arguments for this particular call. For imported functions, as was demonstrated earlier, the names could be read from the import table or, if available, a symbol file; for functions with local linkage, the symbol file is the only source the function name may come from. All the decompilers successfully acquired names for the imported functions, but r2snow and build-in decompiler left the local functions BaseSrvInitializeIniFileMappings() and CreateBaseAcls() unnamed.

Provided a calling convention is known (which is the case for 64-bit machine code stored in a Windows PE file) one could infer partial function prototype by analyzing which registers are initialized and how much data is pushed onto the stack right before the function call; this procedure will also yield the actual parameters. Another way of going about it is by consulting symbol files and standard/system headers. Decompilers retdec-r2plugin and r2ghidra-dec were particularly good at this rather difficult job, whereas results produced by others resembled random guesses, more or less. Without studying the source code, it is hard to tell which of the two methods is employed by each of the plugins; for example, retdec-r2plugin seems to be aware of Windows native API functions as indicated by the lines RtlInitUnicodeString((struct _UNICODE_STRING *)(v1 + 72), v2); and NtCreateFile((int64_t **)&g57, 0x1f01ff, (struct _OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES *)&Handle, (struct _IO_STATUS_BLOCK *)&v76, NULL, 128, 3, 2, 1, NULL, 0);, but, then, it makes a mistake in a RtlCreateTagHeap() call.

Again, to give credit where credit is due, I am including a screenshot of the Cutter’s disassembly window showing off the excellent “function call resolution”-related work done by radare2 itself.

Copy-pasted below, for your convenience, are the declarations for Windows Native API’s RtlInitUnicodeString() and NtQuerySystemInformation().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

void RtlInitUnicodeString(

PUNICODE_STRING DestinationString,

PCWSTR SourceString

);

NTSTATUS NtQuerySystemInformation(

IN SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS SystemInformationClass,

OUT PVOID SystemInformation,

IN ULONG SystemInformationLength,

OUT PULONG ReturnLength

);

Remembering that on 64-bit platforms Windows modules comply with the following calling convention: the first four arguments are passed in rcx, rdx, r8 and r9 respectively (the space of appropriate size still being reserved on stack) and the remaining parameters are pushed onto the stack, observe that radare2 correctly deduced arguments for the calls to RtlInitUnicodeString() at the address 0x180001932 and memcpy() at 0x1800019ed.

With the NtQueryInformation() call (at 0x18000198f), the situation is slightly more complicated: radare2 successfully recognized the second and fourth parameters (passed via rdx and r9 correspondingly), but, evidently, got baffled by an obscure instruction sequence that intended to set ecx to 3 and r8 to 0x30:

1

2

3

xor r9d, r9d

lea ecx, [r9 + 3]

lea r8d, [r9 + 30h]

As for, RtlAllocateHeap(), radare2 did not seem to have the required prototype information at its disposal so it simply ignored the call. Nevertheless, radare2 thoughtfully provides reversers with handy prototypes for a multitude of (other) known functions.

But where do they come from? PDB files? Let us find out!

On Symbols and Inferring Function Prototypes

I felt, the topic of symbols and function prototypes deserved its own section so here we are.

ServerDllInitialization() references two functions with local linkage: CreateBaseAcls() and BaseSrvInitializeIniFileMappings() as well as a myriad of functions imported from ntdll.dll (which we will come back to later). In the following a python script introduced in one of my earlier posts is used to extract function protoypes from symbol files. Like so:

1

2

3

4

5

$ python3 pdb_print_types.py -p basesrv.pdb -f CreateBaseAcls

There is no record with the index 0 in the TPI stream

$ python3 pdb_print_types.py -p basesrv.pdb -fna CreateBaseAcls

There is no type record for CreateBaseAcls ( PROCSYM32.typind = 0 ) in the TPI stream

Oops! The type information stream seems to be missing CreateBaseAcls()’s prototype. This is odd. Maybe the type index is wrong. Let us see.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Python 3.8.5 (default, Jul 28 2020, 12:59:40)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import pdbparse

>>> pdb = pdbparse.parse("basesrv.pdb")

>>> len(pdb.STREAM_TPI.types)

0

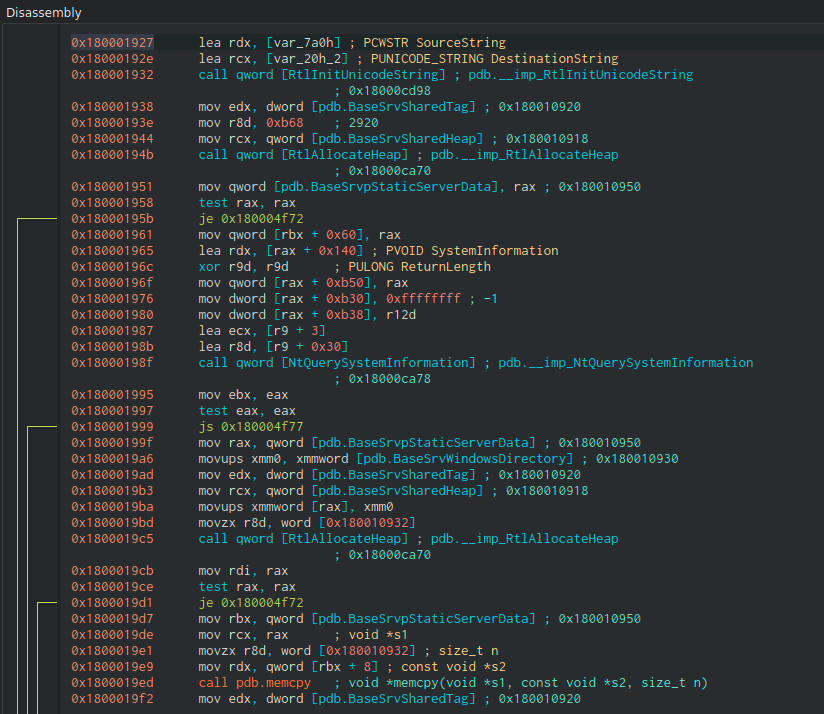

The TPI stream contains no records! It means: no function prototypes, no types for local or global variables. The implication of this discovery is that neither function prototypes, nor types for local or global variables will be available to the decompiler. Just as well, in case of references to local variables, there is none to speak of. On the screenshot below is a hexdump of the relevant potion of the module stream corresponding to the compiland where ServerDllInitialization() is defined (again, I refer the reader to this post if this sentence sounds mysterious).

Debug info about the types of function arguments and local variables as well as their location on the stack is packed in a series of REGREL32 structures, each identifiable by the S_REGREL32 = 0x1111 magic number. However, S_GPROC32 = 0x1110 (global procedure start) and S_SEPCODE = 0x1132 (fragments of separated code) are the only markers (among those pertaining to ServerDllInitialization()) that show up in the hexdump.

It explains why the decompilation outcomes and disassembly listings are the way they are. So far so good, but what about the functions imported from ntdll.dll?

1

2

3

4

5

>>> pdb = pdbparse.parse("ntdll.pdb")

>>> len(pdb.STREAM_TPI.types)

3075

>>> set([ str(pdb.STREAM_TPI.types[t].leaf_type) for t in pdb.STREAM_TPI.types ])

{'LF_ARGLIST', 'LF_MODIFIER', 'LF_FIELDLIST', 'LF_ENUM', 'LF_STRUCTURE', 'LF_BITFIELD', 'LF_PROCEDURE', 'LF_ARRAY', 'LF_POINTER', 'LF_UNION'}

Well, ntdll’s TPI stream contains quite a few type definitions; what is more, there are some function prototypes (as indicated by their fields leaf_type = ‘LF_PROCEDURE’) among them. Unfortunately, since the TPI prototypes are unnamed, we cannot easily determine if our exported functions are included therein, but there is a way. Normally, the global symbol stream would hold a “global procedure reference” that, in turn, “index into” the TPI stream. Why do we not look for, say, RtlInitUnicodeString?

1

2

$ python3 pdb_print_types.py -p ntdll.pdb -fna RtlInitUnicodeString

There is no S_PROCREF-type reference to RtlInitUnicodeString in the global symbols stream.

It is time to lower our standards. After all, we do not have to be so “particular” about it. Any information about the function in question will do.

1

2

3

4

$ pdb_dump.py ntdll.pdb

$ find -name "ntdll.pdb.*" -type f -print0 | xargs -0 strings -f | grep RtlInitUnicodeString

./ntdll.pdb.226: RtlInitUnicodeString

./ntdll.pdb.226: RtlInitUnicodeStringEx

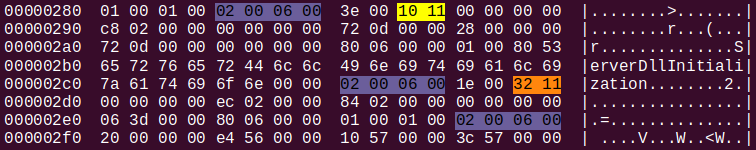

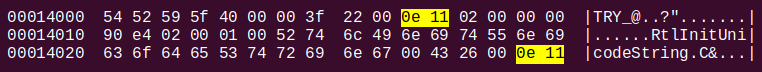

Obtaining a hexdump of ntdll.pdb.226 with the help of command hexdump -C ntdll.pdb.226 and stripping out irrelevant portions of the output, one gets

We seem to have stumbled upon the global symbol stream for the only leaf_type markers present in the vicinity of the “RtlInitUnicodeString” string are that of public symbols (S_PUB32 = 0x110e).

1

2

3

4

5

>>> pdb.STREAM_GSYM.index

226

>>> print(*[ (s.name, hex(s.leaf_type)) for s in pdb.STREAM_GSYM.globals\

... if "name" in dir(s) and s.name == "RtlInitUnicodeString"], sep="\n")

('RtlInitUnicodeString', '0x110e')

Indeed! Now let us see what sort of data comes with a public symbol. Public symbols are stored in the form of an array of PUBSYM32 structures.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct PUBSYM32 {

unsigned short reclen; // Record length

unsigned short rectyp; // S_PUB32

CV_PUBSYMFLAGS pubsymflags;

CV_uoff32_t off;

unsigned short seg;

unsigned char name[1]; // Length-prefixed name

} PUBSYM32;

With this structure, one could locate the symbol in memory once the module is loaded (using the 〈seg : off〉pair). It would have been possible to extract type information from the symbol name had it been decorated. Alas, it is not the case. So this is it! This is all the information you get about the RtlInitUnicodeString() function.

There is nothing extraordinary about this situation. PDB format is designed to be flexible in order to allow including/omitting debugging-related data at developer’s discretion. Microsoft’s symbol files often contain little more than public symbols and some carefully chosen types thereby ensuring no unnecessary information is revealed.

An observant reader will have noticed that a prototype for the very function we are looking at, RtlInitUnicodeString(), has been in radare2 analyzer’s possession all along. Just take a look at the screenshot of Cutter’s disassembly window one more time. Where did it come from? Why, from radare2 itself, of course!

Having pocked around in radare2 source code for a bit, I came across the file /radare2/libr/anal/d/types-windows.sdb.txt; inside of it, there were the following lines:

1

2

3

4

5

RtlInitUnicodeString=func

func.RtlInitUnicodeString.args=2

func.RtlInitUnicodeString.arg.0=PUNICODE_STRING,DestinationString

func.RtlInitUnicodeString.arg.1=PCWSTR,SourceString

func.RtlInitUnicodeString.ret=void

Types-windows.sdb.txt, along with other files complying with the same format, is compiled into a binary with .sdb extension by a utility called sdb.exe and the result goes by the name of “string database”. The string database can then be queried for type information (among other things) within the radare framework.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

$ r2 ntdll.dll

-- Welcome back, lazy human!

[0x180001000]> k anal/types/RtlInitUnicodeString

func

[0x180001000]> k anal/types/func.RtlInitUnicodeString.ret

void

[0x180001000]> k anal/types/func.RtlInitUnicodeString.args

2

[0x180001000]> k anal/types/func.RtlInitUnicodeString.arg.0

PUNICODE_STRING,DestinationString

[0x180001000]> k anal/types/func.RtlInitUnicodeString.arg.1

PCWSTR,SourceString

Radare2 is an open-source cross-platform reverse-engineering framework and as such it was not tailored for Windows code specifically, so I was pleasantly surprised to discover a good portion of Windows Native API prototype set, ready for use on any platform. This is what, along with many other features, makes radare2 excellent in my books.

Concluding Remarks on Automatic Decompilation

With enough practice, one could make great use of the generated (pseudo)-code. For starters, complete code for the faulty routine is not always required for diagnostics; sometimes it is possible to guess what went wrong by simply examining the approximate sequence of system calls. Since I did not have a second computer at my disposal and, hence, an opportunity of debugging the booting process at the early stages remained beyond reach, the crash dump was the only thing I could rely on. Therefore, I needed an understanding of ServerDllInitialization()’s inner workings more thorough than the decompilation output could provide.

Then, I imagine, any of the generated functions, some with more success than others, could be used as a skeleton and build upon by manual reverse engineering. There are artifacts associated with automatic code generation (for example, see the function below) and errors that need to be cleaned up.

1

2

3

4

5

int64_t function_180004f2c(int64_t a1) {

// 0x180004f2c

int64_t result; // 0x180004f2c

return result;

}

In my case the function proved too complicated for this approach to elicit reliable outcome, so, with some dismay, I decided to decompile it manually, from scratch. Besides, I was driven by another, hidden, motive of gaining more experience with radare2 framework. I still consulted the automatically generated code from time to time to double check myself, though.

Reverse-Engineering the ServerDllInitialization()

I will not walk you through the process of decompiling the entire function as it, although not overwhelmingly difficult once one gets a hang of it, is rather tedious and time-consuming. Instead, I have chosen a few non-trivial points of interest that, presumably, require an explanation.

Calling Convention In 64-bit Windows

Once again I will touch upon the subject of calling convention. In my estimation, it is the third time (already!) the topic is being discussed in this series of articles; that said, it is not the worst kind of information to be etched in one’s mind for eternity.

Calling convention encompasses a multitude of aspects: how parameters of various types (integer, floating point, compound types such as classes) are passed, which registers are non-volatile (i.e. their values are preserved across function calls), who, caller or callee, is responsible for deallocating the arguments and so on and so forth. We will not cover the topic in its entirety for basesrv.dll makes use of only a meager subset of features: simple integer parameters (with the exception of structures where pointers are passed in their stead) and integer return values only.

Thus, as specified by the Application Binary Interface (API), on 64-bit Windows systems a so-called “four-register fast-call” calling convention is used, where the first four integer parameters are passed in registers rcx, rdx, r8, and r9, while rax stores the return value.

1

rax = foo(rcx, rdx, r8, r9);

Irrespective of how many parameters the function takes, a “shadow store” 32 bytes in length, which is sufficient for storing four 8-byte parameters, must be allocated (but not necessarily initialized!) on the stack. The remaining parameters, however many there are, are pushed onto the stack in reverse (for the purpose of accommodating a variable number of arguments) order, from right to left.

1

2

swprintf_s(szBuffer, 0x100, L"%ws\\%ld\\AppContainerNamedObjects",

L"\\Sessions", g_SessionId);

Now let us see how these rules apply to the call above.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0x1800018b2 mov eax,dword ptr [basesrv!SessionId (0x180010958)]

0x1800018b8 lea r9,[basesrv!`string' (0x18000cee0)] ; u"Sessions"

0x1800018bf lea r8,[basesrv!`string' (0x18000d0d0)] ; u"%ws\%ld\AppContainerNamedObjects"

0x1800018c6 mov dword ptr [rsp+20h],eax ; g_SessionId

0x1800018ca mov edx,100h

0x1800018cf lea rcx,[rbp+7A0h] ; szBuffer

0x1800018d6 call qword ptr [basesrv!_imp_swprintf_s]

Interestingly, the traditional push/pop pair is not used anywhere in the body of ServerDllInitialization() with the exception of prologue and epilogue. Instead, top of the stack (pointed to by rsp, as usual) remains fixed and parameter initialization is done by move {byte, dword, qword} ptr instructions with addresses relative to the stack pointer. The reason behind it, probably, is the requirement that the stack pointer be 16-bit aligned everywhere, but in prologue and epilogue. In which case, according to Microsoft, offsetting rps by a fixed amount to accommodate, both, local variables and arguments for subroutines, “allows more of the fixed allocation area to be addressed with one-byte offsets”.

NOTE: In this context, the phrase “push onto stack” is idiomatic as no actual push instruction is executed.

Keeping in mind that the arguments are “pushed” from right to left and on x86-64 architectures stack “grows” downwards, towards smaller addresses, one could reconstruct the following initialization sequence: g_SessionId is placed at the address [rsp+20h] (instruction is at 0x1800018c6), then 32 bytes of shadow storage is allocated for the next four arguments: a pointer to L"\\Sessions" is supposed to reside at [rsp+18h] (in reality, it is passes via r9 which is done by the mov instruction at 0x1800018b8), a pointer to L"%ws\\%ld\\AppContainerNamedObjects" – at [rsp+10h], 0x100 – at [rsp+8], and, finally, szBuffer – at the top of the stack. This way the argument layout is the same as it would have been had the cdecl calling convention been used; the difference being that the space allocated for the first four arguments contains garbage.

Beware of Structure Member Alignment

One could, with a degree of certainty, make the reasonable assumption that Microsoft use a tool of their own devising, Visual C++ toolchain, to build their operating system. Furthermore, presence of a so-called Rich header, placed in .dll/.exe files by a linker from aforementioned toolchain, is a good indication of this. In the script below, the “DanS” signature, allegedly derived from the name of Daniel Spalding who ran the linker team in the past, is extracted from basesrv.dll, leaving little to no doubt about correctness of this assumption.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Python 3.8.5 (default, Jul 28 2020, 12:59:40)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import pefile

>>> pe = pefile.PE("basesrv.dll")

>>> "".join([ chr(pe.RICH_HEADER.raw_data[i] ^ pe.RICH_HEADER.key[i]) for i in range(4) ])

'DanS'

Rich headers are extensively utilized in malware identification and, for this reason, a lot of information about them is available online. What I know comes from a conference paper by Webster et al. (2017). For the purposes of this work, we can act on the premise that whatever the documentation says about software compiled with Microsoft development toolchain applies to basesrv.dll as well.

Unless specified otherwise, primitive types such as integer and pointers are naturally aligned, where the notion of natural alignment is defined as follows: “We call a datum naturally aligned if its address is aligned to its size.” (see this). As a result, on x64 systems pointers will only reside at addresses that are multiple of 8. Of course, it is possible to alter the default compiler settings, but it will, most assuredly, incur serious performance issues. Now take a look at the definition of UNICODE_STRING (member offsets are given relative to the beginning of the structure).

1

2

3

4

5

typedef struct _UNICODE_STRING {

WORD Length; //0x0

WORD MaximumLength; //0x2 = sizeof(WORD)

WORD* Buffer; //0x8 assuming the pointers are 8-bytes aligned

} UNICODE_STRING;

Compiler inserts 4 bytes of unused space (padding) between UNICODE_STRING::MaximumLength and UNICODE_STRING::Buffer in order to facilitate the proper alignment, hence an equivalent definition would be:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#pragma pack(push, 1)

typedef struct _UNICODE_STRING {

WORD Length; //0x0

WORD MaximumLength; //0x2

BYTE Padding[4]; //0x4

WORD* Buffer; //0x8

} UNICODE_STRING;

#pragma pack(pop)

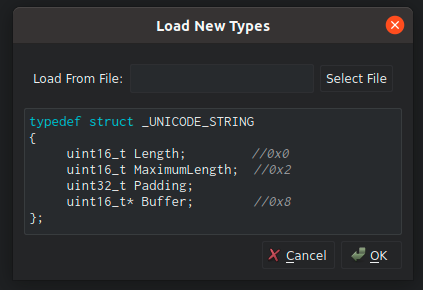

The same in Cutter:

Naturally, this strategy will work only if the structure itself is 8-byte aligned. And according to the documentation, it will be:

The alignment of the beginning of a structure or a union is the maximum alignment of any individual member. Each member within the structure or union must be placed at its proper alignment […] which may require implicit internal padding, depending on the previous member.

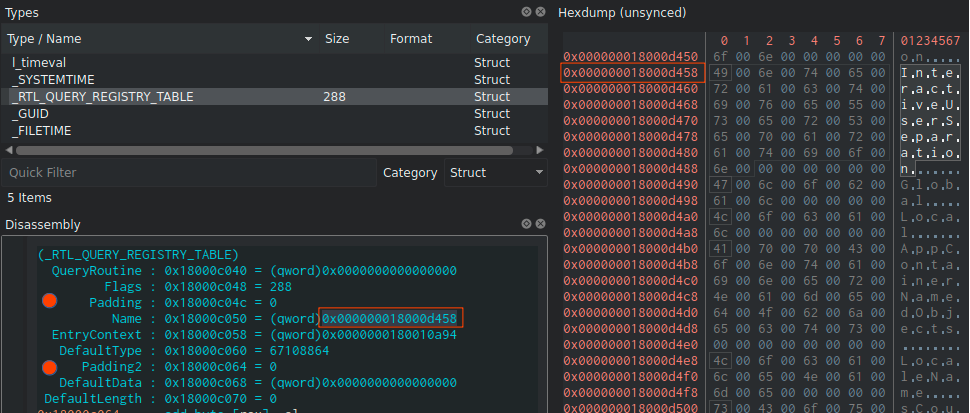

One should keep the alignment in mind when mapping structures to regions of memory and, in particular, when using Cutter’s “Link Type to Address” feature. For example, on the screenshot below two padding arrays were added to ensure RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TABLE::Name and RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TABLE::DefaultData are properly aligned and the structure overall is mapped correctly.

Undocumented Functions and Structures

Speaking of RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TABLE structure, its definition is available for all and sundry here; many other structures, enums, and functions from the Native API, on the other hand, are undocumented. It does not mean, however, that only a select few can get their hands on the corresponding declarations / definitions. Listed below (in no particular order) are the sources where I get my info about undocumented parts of the said API from.

- Geoff Chappell’s web-site

- The Undocumented Functions Of Microsoft Windows NT/2000/XP/Win7 by Tomasz Nowak and Antoni Sawicki

- React OS source code

- Process Hacker’s source code

- Vergilius Project by Svitlana Storchak and Sergey Podobry

Among the undocumented entities are two structures CSR_SERVER_DLL and BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA. The Win10 version of the former could be recovered from this article; here is what Geoff Chappell has to say on the subject:

Microsoft’s only known public release of type information for the

CSR_SERVER_DLLstructure is not in any symbol file but is instead in a statically linked library, named GDISRVL.LIB, that was published with the Device Driver Kit (DDK) for Windows NT 3.51. That type information survives in this library—especially since it has the detail of what would ordinarily be called private symbols—surely was an oversight, but published it is.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

typedef struct _CSR_SERVER_DLL {

ANSI_STRING ModuleName; //0x0

HMODULE ModuleHandle; //0x10

DWORD ServerDllIndex; //0x18

DWORD ServerDllConnectInfoLength; //0x1C

DWORD ApiNumberBase; //0x20

DWORD MaxApiNumber; //0x24

PCSR_API_ROUTINE *ApiDispatchTable;//0x28

BOOLEAN *ApiServerValidTable; //0x30

QWORD Reserved1; //0x38

DWORD PerProcessDataLength; //0x40

DWORD Reserved2; //0x44

LONG (*ConnectRoutine) (CSR_PROCESS*, PVOID, ULONG *); //0x48

VOID (*DisconnectRoutine) (CSR_PROCESS *); //0x50

VOID (*HardErrorRoutine) (CSR_THREAD*, HARDERROR_MSG *);//0x58

PVOID SharedStaticServerData; //0x60

LONG (*AddProcessRoutine) (CSR_PROCESS*, CSR_PROCESS *); //0x68

ULONG (*ShutdownProcessRoutine) (CSR_PROCESS *, ULONG, UCHAR); //0x70

} CSR_SERVER_DLL, *PCSR_SERVER_DLL;

Undocumented structures may change from build to build so one has to make sure the types of declared fields match the instructions that reference them. Luckily, this time they did. For BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA, however, it was not the case. The only place where I could find a definition for this structure was ReactOS source code and, unfortunately, the version they had there differed from the one currently used in basesrv.dll, hence there was nothing left for me but to reconstruct BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA by analyzing the assembler instructions operating on its fields whilst borrowing corresponding names (when present) from ReactOS sources. Here is the end result:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

typedef struct _BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA {

UNICODE_STRING WindowsDirectory; //0x000

UNICODE_STRING WindowsSystemDirectory; //0x010

UNICODE_STRING NamedObjectDirectory; //0x020

char padding1[6]; //0x030 (WindowsMajorVersion, WindowsMinorVersion, and BuildNumber will fit right in)

int16_t CSDNumber; //0x036

int16_t RCNumber; //0x038

WCHAR CSDVersion[128]; //0x03a

char padding2[6]; //0x13a

SYSTEM_TIMEOFDAY_INFORMATION TimeOfDay; //0x140 (sizeof(BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA) = 0x30; https://www.geoffchappell.com/studies/windows/km/ntoskrnl/api/ex/sysinfo/timeofday.htm)

PVOID IniFileMapping; //0x170

NLS_USER_INFO NlsUserInfo; //0x178

char padding3[0x958 - 0x178 - sizeof(NLS_USER_INFO)]; //do not know the NLS_USER_INFO layout in Win10

unsigned char DefaultSeparateVDM; //0x958

unsigned char IsWowTaskReady; //0x959

UNICODE_STRING WindowsSys32x86Directory; //0x960

unsigned char fTermsrvAppInstallMode; //0x970

char paddng5[447]; //0x971

int32_t TermsrvClientTimeZoneId; //0xb30

unsigned char LUIDDeviceMapsEnabled; //0xb34

char padding6[3]; //0xb35

int32_t TermsrvClientTimeZoneChangeNum; //0xb38

char padding7[4]; //0xb3c

UNICODE_STRING AppContainerNamedObjectsDirectory; //0xb40

struct BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA* pSelf; //0xb50

UNICODE_STRING UserObjectsDirectory; //0xb58

} _BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA, *PBASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA;

Error Checking

Many of Windows system calls indicate whether the execution has been successful or not (and if not, the reason why it failed) by returning a value of type NTSTATUS. Indeed, the error code we are interested in, STATUS_OBJECT_NAME_NOT_FOUND, is one of such values. NTSTATUS is a 32-bit integer where the leftmost two bits distinguish error codes from success (or “status”) codes: b00 designates success, b01 – information, b10 – warning, b11 – error, with the latter two being interpreted as failures. As a result, given that NTSTATUS is a signed integer in 2’s complement notation, error codes are identified by a negative sign and the “check if successful” macro is defined (in ntdef.h) as follows:

1

#define NT_SUCCESS(Status) ((NTSTATUS)(Status) >= 0)

which translates into the following set of instructions:

1

2

test eax,eax

js error_handling_code

An Array Initializer

Here is a rather unremarkable array declaration followed by an equally mundane brace-enclosed list of initializers.

1

DWORD pdwAccessMasks[] = { 4, 0x100002, 8, 0x100004, 0 };

What is interesting about this statement is the way it translates into assembler instructions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

0x1800016aa mov dword ptr [rbp+68h],4

;[skipping six instructions]

0x1800016cd mov dword ptr [rbp+6Ch],100002h

;[skipping one instruction]

0x1800016d7 mov dword ptr [rbp+70h],8

0x1800016de mov qword ptr [rbp+74h],100004h

NOTE: Observe that the array initialization is intertwined with other, unrelated, instructions that are omitted from the listing. I remember notions of variable “span” and “live time” from the book called “Code Complete” by Steve McConnell where one is advised to keep all the statements referencing a local variable as close together as possible thereby minimizing the said quantities. Assembler instructions operating on the registers do not adhere to this principle; on the contrary, one often finds instructions generated for multiple high-level statements mixed together. It is usually the result of one optimization or another. For example, load instructions could potentially take many CPU cycles to execute (unless the value is already in cache) and, therefore, are placed some distance away from the instructions that need the loaded value. Unfortunately, it makes the assembly listings difficult to read.

The instruction sequence should be pretty much self-explanatory apart from, possibly, the last mov where an 8-byte qword is recorded on stack instead of the 4-byte initializers hitherto used. Encompassed in this 64-bit value (0x0000000000100004) are the last two initializers: 0x100004 and 0x0 – that are “laid out” in memory correctly thanks to the Little Indian architecture. Of course, it is impossible to distinguish between an array of values and four separate variables (the latter 64-bit in length) until one decompiles the loop that uses the data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

DWORD* pdw = pdwAccessMasks;

do {

ACCESS_MASK mask = pAce->Mask;

pAce->Mask &= 0xFFFF0000;

mask &= *pdw;

mask &= 0x0000FFFF;

if (mask == *pdw)

pAce->Mask |= *(pdw + 1);

pdw += 2; //sizeof(DWORD) == 4

}

while (*pdw != 0);

For the sake completeness, I am posting an excerpt from disassembly listings featuring the instructions that reference pdwAccessMasks array.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

0x180002168 lea rdx,[rbp+68h] ; pdw = pdwAccessMasks

0x180002175 mov eax,4 ; eax = pdwAccessMasks[0]

0x18000217d and ecx,eax ; mask &= *pdw

0x18000235f mov eax,dword ptr [rdx+4] ; pAce->Mask |= *(pdw + 1);

0x180002362 or dword ptr [rcx+4],eax ; (size(DWORD) == 4)

0x18000218a mov eax,dword ptr [rdx+8] ; (8 == 2 * size(DWORD))

0x18000218d add rdx,8 ; pdw += 2

0x180002191 test eax,eax ; while (*pdw != 0)

0x180002193 jne 0x18000217a

Some Useful Macro

The shorter the function the easier it is to analyze so why not define a couple of Macro to keep the code length in check? Macro are preferred to subroutines in this case for they would allow to get the machine code close to the original should the resulting function be compiled; besides, this approach is in line with Microsoft’s coding style (one encounters a plethora of clever Macro in MFC and ATL sources). Let us start with “error checking and clean-up” combinations.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#define HALT_NO_MEM_IF_FALSE(op) if (!(op)) {\

RtlDeleteCriticalSection(&g_BaseSrvDosDeviceCritSec);\

return STATUS_NO_MEMORY;\

}

#define HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(op) if ((op) == NULL) {\

RtlDeleteCriticalSection(&g_BaseSrvDosDeviceCritSec);\

return STATUS_NO_MEMORY;\

}

#define HALT_IF_FAIL(op) ret = op;\

if (!NT_SUCCESS(ret)) {\

RtlDeleteCriticalSection(&g_BaseSrvDosDeviceCritSec);\

return ret;\

}

Yes, I do realize that the first two macro are essentially identical, but having them defined separately improves code readability (or so I hope). Next are the Macro responsible for copying Unicode strings; the first of which allocates the exact number of bytes necessary to hold the string (and, as such, bears the postfix “EXACT”) as opposed to the maximum possible length (specified by the UNICODE_STRING::MaximumLength field).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

#define COPY_UNICODE_STRING_EXACT(to, from) to = from;\

to.MaximumLength = from.Length + sizeof(WORD);\

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(pDst = RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvSharedHeap,\

g_BaseSrvSharedTag, from.Length + sizeof(WORD)))\

memcpy(pDst, to.Buffer, to.MaximumLength);\

to.Buffer = pDst;

#define COPY_UNICODE_STRING(to, from) to = from;\

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(pDst = RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvSharedHeap,\

g_BaseSrvSharedTag, from.MaximumLength))\

memcpy(pDst, to.Buffer, from.MaximumLength);\

to.Buffer = pDst;

An observant reader might have noticed the newly allocated buffer being initialized with the “destination” instead of “source” string and, possibly, found such an arrangement puzzling. Why is that? Take a look at the assembler listing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

0x180001a28 mov rbx,qword ptr [basesrv!BaseSrvpStaticServerData]

0x180001a62 movups xmm0,xmmword ptr [rbp-68h] ; uTmpBuffer is at [rbp-68h]

0x180001a66 movups xmmword ptr [rbx+20h],xmm0 ; NamedObjectDirectory is at the offset 20h

; xmmword is 128 bit-long, so is the UNICODE_STRING structure; hence, the net

; result is g_BaseSrvpStaticServerData->NamedObjectDirectory = uTmpBuffer

0x180001a6a movzx eax,word ptr [rbp-68h] ; eax = uTmpBuffer.Length

0x180001a6e add ax,2; eax = uTmpBuffer.Length + 2

0x180001a72 mov word ptr [rbx+22h],ax

; now NamedObjectDirectory.MaximumLength = uTmpBuffer.Length + 2

0x180001a76 movzx r8d,word ptr [rbp-68h];

0x180001a7b add r8,2

0x180001a7f call qword ptr [basesrv!_imp_RtlAllocateHeap]

; uTmpBuffer.Length + 2 bytes are allocated

0x180001a85 mov rdi,rax ; rax = pDst

0x180001a88 test rax,rax

0x180001a8b je basesrv!ServerDllInitialization+0x38f2 (0000000180004f72)

0x180001a91 mov rbx,qword ptr [basesrv!BaseSrvpStaticServerData]

0x180001a98 mov rcx,rax ; rcx = pDst

0x180001a9b movzx r8d,word ptr [rbx+22h] ; NamedObjectDirectory.MaximumLength

0x180001aa0 mov rdx,qword ptr [rbx+28h] ; NamedObjectDirectory.Buffer

0x180001aa4 call basesrv!memcpy (00000001`800048c1)

; NamedObjectDirectory.MaximumLength bytes are copied from NamedObjectDirectory.Buffer

; to the newly allocated buffer (pDst)

0x180001ab6 mov qword ptr [rbx+28h],rdi ; updating NamedObjectDirectory.Buffer

A pair of movups instructions copies 128 bits of data from uTmpBuffer variable to g_BaseSrvpStaticServerData->NamedObjectDirectory. Not at all coincidentally, the size of UNICODE_STRING is also 16 bytes, therefore the uTmpBuffer structure is copied in its entirety. Since the two structures are identical it does not matter which one serves as the “source” string.

Another potentially baffling thing is the way the length of buffer is computed. Contrary to what your intuition might suggest, UNICODE_STRING::Length holds the string length in bytes (not shorts!); what is more, it does not count the terminating null character even if one is present (which need not be the case). This is why 2 = sizeof(WORD) is added to the size of buffer being allocated.

Below is the Unicode string copy procedure, decompiled by hand.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

pS->NamedObjectDirectory = uTmpBuffer;

//UNICODE_STRING.Length does not include the terminating L"\x0"

pS->NamedObjectDirectory.MaximumLength = uTmpBuffer.Length + sizeof(WORD);

pDst = RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvSharedHeap, g_BaseSrvSharedTag,

uTmpBuffer.Length + sizeof(WORD));

if (pDst == 0) {

RtlDeleteCriticalSection(&g_BaseSrvDosDeviceCritSec);

return STATUS_NO_MEMORY;

}

memcpy(pDst, pS->NamedObjectDirectory.Buffer, pS->NamedObjectDirectory.MaximumLength);

pS->NamedObjectDirectory.Buffer = pDst;

Decompiling Windows Native API Calls That Expect a Pointer to OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES as an Argument

Developers well-versed in WinAPI are, no doubt, familiar with the concept of named objects that constitute the key mechanism behind interprocess communication on Windows. ServerDllInitialization() is responsible for creating directories that would hold these objects. With the introduction of Terminal Services and, then, AppContainer Isolation, this process became much more complicated and, to this end, calls to NtCreateDirectoryObject() became a “staple” of basesrv initialization procedure. Here is a prototype of NtCreateDirectoryObject() I found on http://undocumented.ntinternals.net/.

1

2

3

NTSYSAPI NTSTATUS NtCreateDirectoryObject(HANDLE* DirectoryHandle,

ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES* ObjectAttributes);

Passed as the last argument to this function is a pointer to the OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES structure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct _OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES {

ULONG Length; //0x00

HANDLE RootDirectory; //0x08 due to pointer alignment

PUNICODE_STRING ObjectName; //0x10

ULONG Attributes; //0x18

PVOID SecurityDescriptor; //0x20 due to pointer alignment

PVOID SecurityQualityOfService; //0x28

} OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES;

Consider RootDirectory and SecurityDescriptor fields, both subject to the alignment-related adjustments (winnt.h defines HANDLE as follows: typedef PVOID HANDLE, so pointer alignment rules apply here as well). Let us try and reverse-engineer the assembler snippet below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

0x180001e0a xor ecx,ecx ; ecx = 0

0x180001e0c mov dword ptr [rsp+60h],30h ; oa.Length = 0x30 (=sizeof(OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES))

0x180001e14 mov qword ptr [rsp+68h],rcx ; oa.RootDirectory = NULL

0x180001e19 lea rax,[rbp-68h] ; rax = &uTmpBuffer

0x180001e1d mov qword ptr [rbp-78h],rcx ; oa.SecurityQualityOfService = NULL

0x180001e21 lea r8,[rsp+60h] ; ObjectAttributes = &oa

0x180001e26 lea rcx,[basesrv!BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory] ; DirectoryHandle = &g_BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory

0x180001e2d mov dword ptr [rsp+78h],esi ; oa.Attributes = dwAttributes

0x180001e31 mov edx,0F000Fh ; DesiredAccess = DIRECTORY_ALL_ACCESS | STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED (= 0x0F000F)

0x180001e36 mov qword ptr [rsp+70h],rax ; oa.ObjectName = &uTmpBuffer

0x180001e3b mov qword ptr [rbp-80h],rdi ; oa.SecurityDescriptor = pBNOSd

0x180001e3f call qword ptr [basesrv!_imp_NtCreateDirectoryObject]

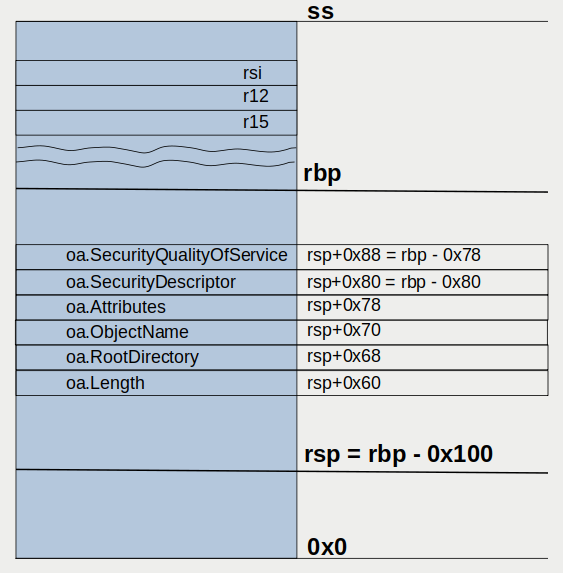

The initialization of OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES is all over the place: it starts by computing addresses relative to rsp and then, half way though, changes to utilizing rbp for this purpose instead, thereby creating the impression that two separate data structures (and not a continuous region of memory) are being initialized. An excerpt from the function prologue should explain this behaviour.

1

2

3

; 3552 bytes are reserved on stack before the new frame starts

0x180001688 lea rbp,[rsp-0DE0h]

0x180001690 sub rsp,0EE0h ; new rsp is offset by 3808 bytes

So, rsp is offset by -0x100 bytes relative to rbp:

rsp = rsp_old - 0x0EE0 = (rbp + 0x0DE0) - 0x0EE0 = rbp - 0x100

hence the rpb-0x80 = rsp+0x80 and rbp-0x78 = rsp+0x88 and the assembler code above translates into this set of statements in C.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

oa.Length = sizeof(OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES); //[rsp+60h] sizeof(OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES) = x30

oa.RootDirectory = NULL; //[rsp+68h] 'cos of pointer alignment

oa.ObjectName = &uTmpBuffer; //[rsp+70h]

oa.Attributes = dwAttributes; //[rsp+78h]

oa.SecurityDescriptor = pBNOSd; //[rsp+80h] = [rpb-80h]

oa.SecurityQualityOfService = NULL; //[rsp+88h] = [rbp-78h]

NtCreateDirectoryObject(&g_BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory,

DIRECTORY_ALL_ACCESS | STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED, &oa);

Is my explanation crystal clear? That is alright. No worries. I created a rather confusing illustration to remedy this mishap.

NOTE: People in the habit of reading books might be haunted by a vague, yet disturbing, feeling that something is inherently wrong with this picture. Because it is. Contrary to the established practice, the zero address is placed at the bottom (rather than the “conventional” top) of canvas.

Here is another example that, one hopes, deserves our attention.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

0x180001c77 mov rax,qword ptr [basesrv!BaseSrvpStaticServerData]

0x180001c7e lea r8,[rsp+60h]

0x180001c83 xorps xmm0,xmm0

0x180001c86 lea rcx,[rbp-10h]

0x180001c8a mov edx,20019h

0x180001c8f mov byte ptr [rax+958h],r12b

0x180001c96 lea rax, [18000c0e8h] ; g_WOWRegistryKeyName

0x180001c9d mov qword ptr [rsp+70h],rax

0x180001ca2 mov dword ptr [rsp+60h],30h

0x180001caa mov qword ptr [rsp+68h],r12

0x180001caf mov dword ptr [rsp+78h],40h

0x180001cb7 movdqu xmmword ptr [rbp-80h], xmm0

0x180001cbc call qword ptr [basesrv!_imp_NtOpenKey]

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES is initialized in more or less the same way as before with the exception of the last two members, where that attention-grabbing thing happens. As was mentioned previously, xmm0 is 128-bit long, which is the length of OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES::SecurityDescriptor and OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES::SecurityQualityOfService, combined, so both could be zeroed out in one go by the movdqu xmmword ptr [rbp-80h], xmm0 instruction, provided xmm0 = 0 (the latter is accomplished by xorps xmm0,xmm0). As usual, the (manually) decompiled version is given below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

HANDLE hKey; //[rbp-10h]

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa;

oa.Length = sizeof(OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES); //sizeof(OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES) = 0x30

oa.RootDirectory = NULL;

oa.ObjectName = &g_WOWRegistryKeyName;

oa.Attributes = OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE;

oa.SecurityDescriptor = NULL;//zeroing out 128 bits of data at [rbp-80h]=[rsp+80h] using mmx instructions

oa.SecurityQualityOfService = NULL;

NtOpenKey(&hKey, READ_CONTROL | KEY_QUERY_VALUE | KEY_ENUMERATE_SUB_KEYS |

KEY_NOTIFY, &oa);

Big Reveal and Analysis

This collection of amusing bits demonstrating idiosyncrasies of Microsoft’s C compiler came into being as a result of me reverse-engineerig the entire ServerDllInitialization() and (parts of) two utility functions it called. I did so solely by analyzing disassembly listings and following a control flow graph, while consulting the code generated by automatic decompilers from time to time to double check myself. Writing a program that would call basesrv’s functions with dummy parameters and stepping through the machine code with a debugger would have been and easier route or, at the very least, a helpful supplementary technique. However, I did not find an easy way of doing it under Linux.

In the following I present the result of this undertaking. Let us begin with global variables. Of these, there are two kinds: ones with the corresponding names present among global symbols and unnamed variables that the reverser has a privilege of naming on her own. As for the types, none were found in the basesrv.pdb and, therefore, they had to be inferred from the way the variable was used.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

HANDLE g_BaseSrvHeap;

HANDLE g_BaseSrvSharedHeap;

UNICODE_STRING g_BaseSrvCSDString;

SHORT g_BaseSrvCSDNumber[2];

DWORD g_InteractiveUserNameSpaceSeparation;

HANDLE g_BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory;

HANDLE g_BaseSrvUserObjectDirectory;

SYSTEM_BASIC_INFORMATION g_SysInfo;

RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TABLE g_BaseServerRegistryConfigurationTable =

{

NULL,

RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_DIRECT,

L"CSDVersion",

&g_BaseSrvCSDString, //0x180010960

REG_NONE,

NULL,

0

};

RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TABLE g_BaseServerRegistryConfigurationTable1 =

{

NULL,

RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_DIRECT,

L"CSDVersion",

&g_BaseSrvCSDNumber, //0x180010970

REG_NONE,

NULL,

0

};

RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TABLE g_BnoRegistryConfigurationTable =

{

NULL,

RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_TYPECHECK | RTL_QUERY_REGISTRY_DIRECT,

L"InteractiveUserSeparation",

&g_InteractiveUserNameSpaceSeparation,

0x4000000,

NULL,

0

};

These were the variables already named (though I took a liberty of adding a “g_” prefix to distinguish them from local variables). Now to the “anonymous” ones!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

UNICODE_STRING g_uWOWRegistryKeyName = { 0x6c, 0x6e,

L"Registry\\Machine\\System\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\WOW" };

UNICODE_STRING g_uWOWRegistryValueName = { 0x24, 0x26, L"DefaultSeparateVDM" };

UNICODE_STRING g_uGlobal = { 0xc, 0xe, L"Global" };

UNICODE_STRING g_uAppContainerNamedObjects = { 0x30, 0x32,

L"AppContainerNamedObjects" };

UNICODE_STRING g_uBaseNamedObjectsNZSLink = { 0x22, 0x24,

L"\\BaseNamedObjects" };

UNICODE_STRING g_uLocal = { 0xa, 0xc, "Local" };

With all these declarations and definitions in place we can finally present the function itself. A round of applause, ladies and gentlemen.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

NTSTATUS ServerDllInitialization(struct CSR_SERVER_DLL* pInput)

{

DWORD pdwAccessMasks[] = { 4, 0x100002, 8, 0x100004, 0 };

//https://www.vergiliusproject.com/kernels/x64/Windows%2010%20|%202016/1809%20Redstone%205%20(October%20Update)/_PEB

g_SessionId = ((struct _PEB*)(__readgsqword(0x60)))->SessionId;

g_ServiceSessionId = RtlGetCurrentServiceSessionId();

//OBJ_PERMANENT: If this flag is specified, the object is not deleted when all open handles are closed.

DWORD dwAttributes = (OBJ_OPENIF | OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE) | (g_SessionId == g_ServiceSessionId ? OBJ_PERMANENT : 0);

g_BaseSrvHeap = ((struct _PEB*)(__readgsqword(0x60)))->ProcessHeap;

g_BaseSrvTag = RtlCreateTagHeap(g_BaseSrvHeap, 0, L"BASESRV!", L"TMP");

g_BaseSrvSharedHeap = pInput->SharedStaticServerData;

g_BaseSrvSharedTag = RtlCreateTagHeap(pInput->SharedStaticServerData, 0, L"BASESRV!", L"INIT");

pInput->ApiNumberBase = 0;

pInput->ApiDispatchTable = g_BaseServerApiDispatchTable;

pInput->ApiServerValidTable = g_BaseServerApiServerValidTable;

pInput->ConnectRoutine = g_BaseClientConnectRoutine;

pInput->DisconnectRoutine = g_BaseClientDisconnectRoutine;

pInput->MaxApiNumber = 0x1D;

pInput->PerProcessDataLength = 8;

NTSTATUS ret = RtlInitializeCriticalSection(&g_BaseSrvDosDeviceCritSec);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(ret))

return ret;

WORD czWindowsDirectory[WINDOWS_DIR_MAX_LEN];

UNICODE_STRING uSysRoot = { 0, WINDOWS_DIR_MAX_LEN * sizeof(WORD), czWindowsDirectory }; //[rbp+20h]

RtlExpandEnvironmentStrings_U(NULL, g_UnexpandedSystemRootString, &uSysRoot, 0); //g_UnexpandedSystemRootString == L"%SystemRoot%"

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_FALSE(uSysRoot.Length != WINDOWS_DIR_MAX_LEN * sizeof(WORD))

if (uSysRoot.Length & 0xFFFE == WINDOWS_DIR_MAX_LEN * sizeof(WORD)) {

_report_rangecheckfailure (0x0000000180004618)

asm{ int 3}

}

czWindowsDirectory[uSysRoot.Length] = L'\x0'; //uSysRoot.Length does not count the terminating NULL (and it is not always present)

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_FALSE(RtlCreateUnicodeString(&g_BaseSrvWindowsDirectory, czWindowsDirectory))

wcscat_s(czWindowsDirectory, WINDOWS_DIR_MAX_LEN, L"\\system32");

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_FALSE(RtlCreateUnicodeString(&g_BaseSrvWindowsSystemDirectory, czWindowsDirectory))

WORD szBaseNamedObjects[NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN];

if (g_SessionId != g_ServiceSessionId)

swprintf_s(szBaseNamedObjects, NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN, L"%ws\\%ld\\BaseNamedObjects", L"Sessions", g_SessionId);

else

wcscpy_s(szBaseNamedObjects, NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN, L"\\BaseNamedObjects");

WORD szAppContainerNamedObjects[NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN]; //[rbp+7A0h]

swprintf_s(szAppContainerNamedObjects, NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN, L"%ws\\%ld\\AppContainerNamedObjects", L"Sessions", g_SessionId);

WORD szBaseUserObjects[NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN]; //[rbp+5A0h]

RtlStringCchPrintfW(szBaseUserObjects, NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN, L"%ws\\%ld\\BaseNamedObjects", L"Sessions", g_SessionId);

struct UNICODE_STRING uBaseUserObjects; //[rbp-30h]

RtlInitUnicodeString(&uBaseUserObjects, szBaseUserObjects);

struct UNICODE_STRING uTmpBuffer; //[rbp-68h]

RtlInitUnicodeString(&uTmpBuffer, szBaseNamedObjects);

struct UNICODE_STRING uAppContainerNamedObjects; //[rbp-20h]

RtlInitUnicodeString(&uAppContainerNamedObjects, szAppContainerNamedObjects);

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(g_BaseSrvpStaticServerData = RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvSharedHeap, g_BaseSrvSharedTag, 0x0B68))

pInput->SharedStaticServerData = g_BaseSrvpStaticServerData;

struct BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA* pS = (struct BASE_STATIC_SERVER_DATA*)(g_BaseSrvpStaticServerData);

pS->pSelf = g_BaseSrvpStaticServerData; //xb50

pS->TermsrvClientTimeZoneId = TIME_ZONE_ID_INVALID; //0xb30

pS->TermsrvClientTimeZoneChangeNum = 0; //0x38

HALT_IF_FAIL(NtQuerySystemInformation(SystemTimeOfDayInformation, &pS->TimeOfDay, sizeof(SYSTEM_TIMEOFDAY_INFORMATION), NULL))

COPY_UNICODE_STRING(pS->WindowsDirectory, g_BaseSrvWindowsDirectory)

COPY_UNICODE_STRING(pS->WindowsSystemDirectory, g_BaseSrvWindowsSystemDirectory)

*(DWORD*)(&pS->WindowsSys32x86Directory.Length) = 0;

pS->WindowsSys32x86Directory.Buffer = NULL;

COPY_UNICODE_STRING_EXACT(pS->NamedObjectDirectory, uTmpBuffer)

COPY_UNICODE_STRING_EXACT(pS->AppContainerNamedObjectsDirectory, uAppContainerNamedObjects)

COPY_UNICODE_STRING_EXACT(pS->UserObjectsDirectory, uBaseUserObjects)

pS->fTermsrvAppInstallMode = FALSE;

WCHAR szCSDVersion[200]; //[rbp+2d8h], 200 == 0xC8

g_BaseSrvCSDString.MaxLength = 200;

g_BaseSrvCSDString.Length = 0;

g_BaseSrvCSDString.Buffer = szCSDVersion;

ret = RtlQueryRegistryValuesEx(RTL_REGISTRY_WINDOWS_NT, L"\x0", &g_BaseServerRegistryConfigurationTable1, NULL, NULL);

if (NT_SUCCESS(ret)) {

pS->CSDNumber = g_BaseSrvCSDNumber[0];

pS->RCNumber = g_BaseSrvCSDNumber[1];

}

else

*(int32_t*)(pS->CSDNumber) = 0L;

ret = RtlQueryRegistryValuesEx(RTL_REGISTRY_WINDOWS_NT, L"\x0", &g_BaseServerRegistryConfigurationTable, NULL, NULL);

if (NT_SUCCESS(ret))

wcsncpy_s(pS->CSDVersion, 128, g_BaseSrvCSDString.Buffer, g_BaseSrvCSDString.Length / sizeof(WCHAR));

else

pS->CSDVersion[0] = L'\x0';

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlInitUnicodeStringEx(&g_BaseSrvCSDString, NULL))

HALT_IF_FAIL(NtQuerySystemInformation(SystemBasicInformation, &g_SysInfo, sizeof(SYSTEM_BASIC_INFORMATION), NULL))

HALT_IF_FAIL(BaseSrvInitializeIniFileMappings())

pS->DefaultSeparateVDM = FALSE;

HANDLE hKey; //[rbp-10h]

struct OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa; //[rsp+60h]

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &g_uWOWRegistryKeyName, OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE, NULL, NULL);

ret = NtOpenKey(&hKey, READ_CONTROL | KEY_QUERY_VALUE | KEY_ENUMERATE_SUB_KEYS | KEY_NOTIFY, &oa);

if (NT_SUCCESS(ret)) {

ULONG len; //[rbp+30h]

ret = NtQueryValueKey(hKey, &g_uWOWRegistryValueName, KeyValuePartialInformation, czWindowsDirectory, WINDOWS_DIR_MAX_LEN * sizeof(DWORD), &len);

if (NT_SUCCESS(ret)) {

struct _KEY_VALUE_PARTIAL_INFORMATION* pKi = (struct _KEY_VALUE_PARTIAL_INFORMATION*)(czWindowsDirectory);

switch (pKi->Type) {

case REG_DWORD:

if (*(DWORD*)(pKi->Data) != 0)

pS->DefaultSeparateVDM = TRUE;

break;

case REG_SZ:

if (wcsicmp((WCHAR*)(pKi->Data), L"yes") == 0 || wcsicmp((WCHAR*)(pKi->Data), L"1") == 0)

pS->DefaultSeparateVDM = TRUE;

break;

}

}

NtClose(hKey);

}

pS->IsWowTaskReady = FALSE;

RtlQueryRegistryValuesEx(RTL_REGISTRY_CONTROL, L"Session Manager\\NamespaceSeparation", &g_BnoRegistryConfigurationTable, NULL, NULL);

//did not check the return value

struct SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR* pBNOSd = (struct SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR*)(RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvHeap, g_BaseSrvTag, 0x400)); //x400 ???

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(pBNOSd)

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlCreateSecurityDescriptor(pBNOSd, SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR_REVISION))

struct SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR* pBLowBoxOSd = (struct SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR*)(RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvHeap, g_BaseSrvTag,

sizeof(SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR)));

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(pBLowBoxOSd)

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlCreateSecurityDescriptor(pBLowBoxOSd, SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR_REVISION))

struct SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR* pBUserOSd; //[rbp+8]

struct ACL* pBUserODAcl = NULL; //[rbp-38h]

if (g_InteractiveUserNameSpaceSeparation) {

pBUserOSd = (struct SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR*)(RtlAllocateHeap(g_BaseSrvSharedHeap, g_BaseSrvSharedTag, sizeof(SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR)));

HALT_NO_MEM_IF_NULL(pBUserOSd)

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlCreateSecurityDescriptor(pBUserOSd, SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR_REVISION))

}

struct ACL* pBNODAcl; //[rbp-40h]

struct ACL* pRestrictedDAcl; //[rbp]

struct ACL* pBLowBoxODAcl; //[rbp-8h]

struct ACL* pBNOSAcl; //[rbp-48h]

HALT_IF_FAIL(CreateBaseAcls(&pBNODAcl, &pRestrictedDAcl, &pBLowBoxODAcl, &pBNOSAcl, g_InteractiveUserNameSpaceSeparation ? &pBUserODAcl : NULL))

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlSetDaclSecurityDescriptor(pBNOSd, TRUE, pBNODAcl, FALSE))

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlSetSaclSecurityDescriptor(pBNOSd, TRUE, pBNOSAcl, FALSE))

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlSetDaclSecurityDescriptor(pBLowBoxOSd, TRUE, pBLowBoxODAcl, FALSE))

if (g_InteractiveUserNameSpaceSeparation)

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlSetDaclSecurityDescriptor(pBUserOSd, TRUE, pBUserODAcl, FALSE))

//Creating \BaseNamedObjects and \Sessions\sid\BaseNamedObjects directories

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &uTmpBuffer, dwAttributes, NULL, pBNOSd);

HALT_IF_FAIL(NtCreateDirectoryObject(&g_BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory, DIRECTORY_ALL_ACCESS | STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED, &oa))

//Creating Sessions\sid\AppContainerNamedObjects directories

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &uAppContainerNamedObjects, dwAttributes, NULL, pBLowBoxOSd);

HALT_IF_FAIL(NtCreateDirectoryObject(&g_BaseSrvLowBoxObjectDirectory, DIRECTORY_ALL_ACCESS | STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED, &oa))

if (g_SessionId == g_ServiceSessionId) {

//I got the value of ObjectSessionInformation from: https://processhacker.sourceforge.io/doc/ntobapi_8h.html#a95bdc934501aaea6ec12ae1b4cd31f8a

HALT_IF_FAIL(NtSetInformationObject(g_BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory, ObjectSessionInformation, NULL, 0))

if (g_SessionId != 0) {

WCHAR szBuffer[NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN]; //[rbp+9A0h]

swprintf_s(szBuffer, NAMED_OBJECTS_DIR_MAX_LEN, L"%ws\\%ld\\BaseNamedObjects", L"\\Sessions", g_SessionId);

struct UNICODE_STRING uBaseNamedObjectsNZS; //[rbp+48h]

RtlInitUnicodeString(&uBaseNamedObjectsNZS, szBuffer);

HANDLE hBNOLink; //[rbp-70]

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &uBaseNamedObjectsNZS, dwAttributes, NULL, pBNOSd);

ret = NtCreateSymbolicLinkObject(&hBNOLink, DIRECTORY_QUERY | STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED, &oa, &g_uBaseNamedObjectsNZSLink);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(ret))

return ret; //No, the critical section is not released here

NtClose(hBNOLink);

}

}

if (g_InteractiveUserNameSpaceSeparation && g_SessionId == 0) {

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &uBaseUserObjects, dwAttributes, NULL, pBUserOSd);

HALT_IF_FAIL(NtCreateDirectoryObject(&g_BaseSrvUserObjectDirectory, DIRECTORY_ALL_ACCESS | STANDARD_RIGHTS_REQUIRED, &oa))

}

//ProcessLUIDDeviceMapsEnabled is defined here: https://processhacker.sourceforge.io/doc/ntpsapi_8h_source.html

DWORD bLUIDDeviceMapsEna;

ret = NtQueryInformationProcess(INVALID_HANDLE, ProcessLUIDDeviceMapsEnabled, &bLUIDDeviceMapsEna, 4, NULL);

pS->LUIDDeviceMapsEnabled = NT_SUCCESS(ret) ? bLUIDDeviceMapsEna : 0;

if (pS->LUIDDeviceMapsEnabled)

HALT_IF_FAIL(RtlInitializeCriticalSectionAndSpinCount(&g_BaseSrvDDDBSMCritSec, 0x80000000))

//"Sessions\sid\BaseNamedObjects\Global" → "\BaseNamedObjects" (logon session)

//"\BaseNamedObjects\Global" → "\BaseNamedObjects" (for service)

HANDLE hBNOLink; //[rbp-70h]

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &g_uGlobal, dwAttributes, g_BaseSrvNamedObjectDirectory, pBNOSd);