A Tale of Omnipotence or How a Windows Update Broke Ubuntu Live CD

Introduction

If you are known as a “grandkid who can fix computers”, you, beyond a shadow of a doubt, carry an emergency bootable flash drive in your pocket. If you are actually deserving of the title, this flash drive, probably, contains a custom-build Linux image with all the tools necessary to save the world. Me? Lacking this degree of sophistication, I simply use Ubuntu Live CD for this purpose; it allows me to boot Ubuntu on the majority of computers without disabling Secure Boot or enrolling MOK first. For years, my tiny PC rescue operation was running smoothly until one day, a couple of weeks ago, it did not.

On the first attempt to boot, UEFI firmware informed me that “invalid signature” was detected and suggested I “check secure boot policy”, and on the second – the USB thumb drive simply disappeared from the boot options. A spare flash drive did not work either thereby making the hypothesis of data corruption leading to the bootloader’s signature becoming invalid highly unlikely. The UEFI message having given out a rather strong hint as to what might be happening, I disabled Secure Boot and proceeded with the task at hand.

It is all well and good, but the incident left me in a state of confusion, feeling like a character from Amélie someone played a cruel joke on. Surely, there was no need to disable Secure Boot in the past. After I was done with the pointless exercise in questioning my sanity, I took to a search engine, suspecting the joke must have been the doing of one Windows update or other. Lo and behold, the answer surfaced pretty quickly – a security update issued on the 9th of August and labeled KB5012170 was reported to change dbx, a variable pertaining to Secure Boot.

This post aims to explain why and how a Windows update (KB5012170, in particular) may affect bootability of another operating system stored separately, on a thumb drive. The explanation will rely heavily on the understanding of UEFI Secure Boot, so let us begin with describing what it is and how it works.

UEFI Secure Boot

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) is a publicly available specification of the interface provided by the platform firmware. The interface is intended to be used primarily by operating systems and consists in boot- and run-time service calls. For simplicity, think of it as a next generation of BIOS, surpassing and replacing legacy BIOS API.

Secure Boot is a protocol ensuring that only authenticated software runs along certain execution paths; normally, it constitutes a key step in achieving a global OS security objective. Fedora, for example, (admirably succinctly) identifies its objective as “preventing the execution of unsigned code in kernel mode”.

On its part, UEFI-compatible firmware guarantees that only cryptographically signed (exceptions apply) binaries are run in the pre-boot environment; these include UEFI applications (of which the famous BIOS-style setup is a special case), firmware drivers (such as option ROMs), and, most notably, operating system bootloaders, which are then delegated the responsibility of meeting the security objective. To this end, UEFI standard defines the format digital signatures and signing certificates must comply with as well as an interface to setup the root of trust. In addition, UEFI provides a means of white-listing unsigned modules and revoking past signatures and certificates (should the vulnerabilities in the signed modules be found).

In Windows realm, Secure Boot is an integral part of Microsoft’s Trusted Boot Architecture that operates in two stages: Secure Boot, it “checks all code that runs before the operating system and checks the OS bootloader’s digital signature”, and Trusted Boot, when “the Windows bootloader verifies the digital signature of the Windows kernel before loading it” and “the Windows kernel, in turn, verifies every other component of the Windows startup process, including boot drivers, startup files, and your antimalware product’s early-launch antimalware (ELAM) driver” (see the documentation). Ubuntu treats secure boot in a similar fashion; according to Mathieu Trudel-Lapierre:

The whole concept of Secure Boot requires that there exists a trust chain, from the very first thing loaded by the hardware (the firmware code), all the way through to the last things loaded by the operating system as part of the kernel: the modules. In other words, not just the firmware and bootloader require signatures, the kernel and modules too.

In a nutshell, the idea is rather simple and implemented similarly across all the operating systems employing the strategy. Every module on the OS boot path verifies the signatures of every executable it launches and every binary (and sometimes, even configuration file) it loads into its address space, elimination of bootkits being the chief purpose of this meticulous process. UEFI ensures that the first module on the path, the bootloader, is the right one.

How does UEFI firmware know if the binary is “right”? To facilitate the identification, there are two variables defined in the UEFI specification: db and dbx; their values, being stored in NVRAM, persist across reboots. Somewhat confusingly, both of these variables are referred to as “signature databases” even though they do not normally hold cryptographic signatures; here, the term “signature” is used in a more general sense and refers to a string of bytes in some way identifying the object. db, a white list, lists hashes of the binaries allowed to run (even if they are unsigned) and stores public keys (wrapped in certificates) that are to be used to verify the signatures. dbx, a black list, is meant as a revocation list for the entries in db. Each element in dbx is of one of four types (see this post):

- a hash of an executable image,

- a cryptographic certificate,

- a cryptographic signature of an executable image,

- a hash of a cryptographic certificate.

(Though, in practice, I have only encountered entries of the first two types.) dbx is consulted first: if a hash of the binary is in the database or the binary is signed with the certificate listed in dbx, it is discarded immediately; then the UEFI firmware is expected to make sure the binary is either signed with a certificate stored in db or its hash is listed there and only then the code in the binary in question is allowed to execute.

Key Management on Windows-certified Platforms

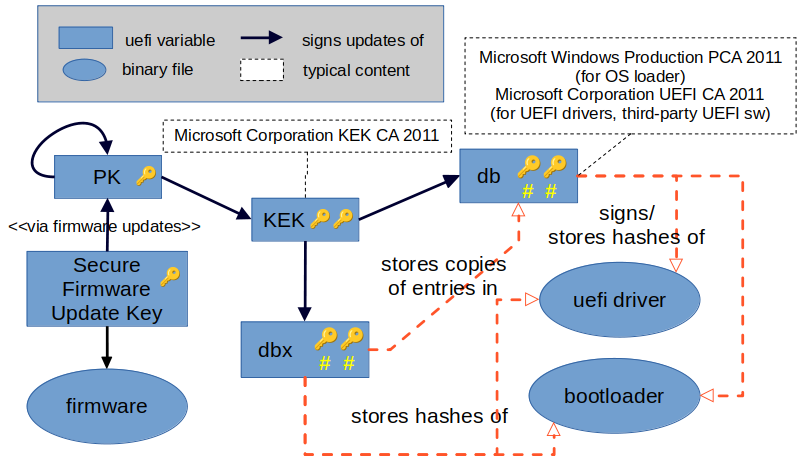

Naturally, there must be a way of updating the signature databases: operating systems are evolving all the time (not to mention the vulnerabilities, that are appearing in equal pacing) but it should be done in a secure manner. Here is when the update-related part of the Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) comes into play. The PKI description that follows is based on the Windows Secure Boot Key Creation and Management Guide for the systems meeting Windows Hardware Certification requirements since these are the systems one encounters (along with tea and home-made biscuits) in the places one visits with a bootable flash drive in one’s pocket. While… perusing the said guide, I put together a diagram illustrating various relationships between the cryptographic keys and UEFI variables mentioned there; it might be helpful to turn to it from time to time as I progress with the explanation of the update procedure. Here it is.

Windows-certified computers come with a pretty Windows logo sticker and two certificates preinstalled in db: Microsoft Windows Production PCA 2011 (58:0a:6f:4c:c4:e4:b6:69:b9:eb:dc:1b:2b:3e:08:7b:80:d0:67:8d) and Microsoft Corporation UEFI CA 2011 (46:de:f6:3b:5c:e6:1c:f8:ba:0d:e2:e6:63:9c:10:19:d0:ed:14:f3) – the former being used to sign Windows bootloader and the latter – essentially, for everything else (third-party UEFI drivers, bootloaders of “alternative” operating systems, etc). A software developer can request that his or her module be signed, provided it passes a review, by Microsoft’s signing service. OEMs often add certificates of their own so that they can ship custom UEFI applications and drivers with their platform. As for dbx, depending on the year of production, initially it may contain revoked entries, known at the time, or be empty (apart for, possibly, a dummy all-zeros value).

UEFI defines a runtime (i.e. available post-boot) service call allowing to change the value of a UEFI variable in NVRAM, including db and dbx:

1

2

3

4

5

EFI_STATUS SetVariable(IN CHAR16* VariableName,

IN EFI_GUID* VendorGuid,

IN UINT32 Attributes,

IN UINTN DataSize,

IN VOID* Data);

So what is the catch? Any rootkit could do away with “this secure boot of yours” in milliseconds. In order to prevent it from happening, at runtime, SetVariable() accepts signed values only, that is, a cryptographic signature of the new value must be prepended (along with some metatdata) to the value itself; the result is to be placed in a buffer, a pointer to which is then passed in the Data parameter. The public key that is to verify the signature is stored, wrapped in a certificate, in another UEFI variable called KEK (aka Key Exchange Keys). Windows computers are shipped with only one certificate in KEK: Microsoft Corporation KEK CA 2011 (31:59:0b:fd:89:c9:d7:4e:d0:87:df:ac:66:33:4b:39:31:25:4b:30), therefore updating db and dbx is the prerogative of Microsoft, who delivers the updates in the form of signature databases, pre-signed with the private counterpart of its KEK key.

Ideally, enrolled in KEK, there must be at least one certificate per vendor of every operating system on the computer, so that all of them could decide which bootloaders and drivers are allowed to run and contribute to keeping the revocation list up-to-date (naturally, care should be taken to avoid conflicts). In reality, Windows being the most commonly used operating system, Microsoft plays the role of an ultimate authority in the “enterprise”. I have already mentioned the possibility (and, indeed, the practice) of signing bootloaders for “alternative” OSs with Microsoft’s key via the company’s signing service. What is more, maintaining a unified UEFI revocation list (i.e. the dbx contents) is a coordinated effort of security researches and major OS vendors across the globe; the official version thereof, available for downloading to anyone wishing to take the matter of updating dbx into their own hands at uefi.org, comes presigned by Microsoft.

That said, UEFI specification still provides the option to rewrite KEK contents. Of course, there is a caveat: the new value must also be signed, this time with a private counterpart of the key stored in yet another UEFI variable – PK (stands for “Platform Key”). OEM (Asus, Dell, HP, Lenovo, etc.) is the entity who owns it and, therefore, decides who should be authorized to handle the white-list/black-list updates.

UEFI specification describes secure boot setup in the terms of device authentication and module authorization; the key notions here are those of platform owner and authorized user. Platform owner is the entity that has in its possession a private key matching the public key stored in PK, i.e. the manufacturer of your computer.

NOTE:

Of course, using UEFI setup (often called “BIOS setup” so as not to confuse the users), it is perfectly possible to take ownership of your computer by replacing the platform key with your own (with a subsequent update of KEK and, possibly, db in a cascade fashion), but, then, it is quite rare that grannies are caught engaged in this murky activity.

Authorized user is a holder of the private counterpart to a public key (there could be several of them) residing in KEK. That will be Microsoft. Now that we have established our place in this world, let us continue with PKI description.

Secure Firmware Update Key, the ultimate key to rule them all, is not actually a part of UEFI specification (as far as I could tell). However, according to the aforementioned guide, Windows Hardware Certification demands this key be “permanently burned into fuses on PC”; it is then used to verify the firmware updates. Firmware updates, in turn, can rewrite PK’s value and, more broadly, alter the entire authentication/authorization policy (say, to implement a new version of the standard). All these factors combined make the key an integral part of PKI, so it seemed worth mentioning.

Important Notes on Certificate Chaining

To complete the theoretical framework, I would like to bring to your attention a few points.

First of all, signing an update to the variable containing a certificate is not the same as signing the certificate itself: a KEK update, for example, may contain not just one, but an array of certificates, complete with an equal number of corresponding guids, each disclosing the entity responsible for enrolling the certificate, a guid identifying the certificate type, and a timestamp. When signing the update, digest of the entire structure is computed and then encrypted with the private key; as a result, returning to our example, certificates in PK and KEK do not form a chain. Besides that, the update signature is not stored along with the variable value, it is discarded as soon as verification is complete.

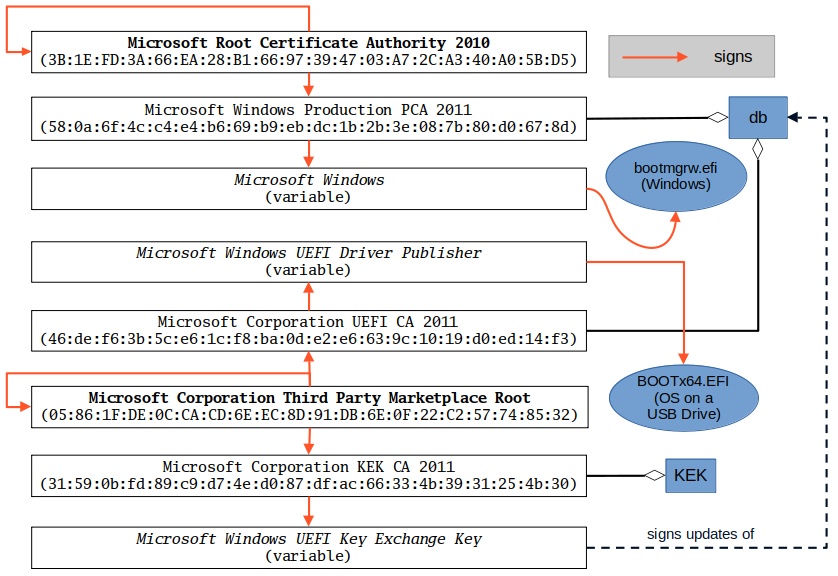

Second of all, by saying “signed with a certificate stored in variable V”, I actually mean “signed with a certificate that can be chained to the certificate stored in V”, but do not state so explicitly to avoid the word clutter. As a rule, executable images and updates are signed with end-entity certificates, generated (often) one per signature and chained to the certificates known to the UEFI firmware. These short-term certificates are stored as part of the signatures, in headers of their respective modules or update files.

Finally, Microsoft certificates residing in KEK and db are not actually root certificates (in the sense that they are not self-signed), but they still can be considered the “roots of trust” for the operations they are meant to authenticate since the UEFI firmware, upon discovering a match in KEK and db, will look no further.

In light of these remarks, the diagram below will present an updated, more precise, view of the relationship between certificates, binaries, and certain UEFI variables.

What Has Happened

A proper understanding of the UEFI secure boot secured, inferring what has happened from the update title alone becomes a matter of utmost triviality. Ubuntu bootloader must have somehow ended up in the updated dbx. Let us check if the guess is correct. I suggest using efi-readvar utility from efitools for the purpose.

1

2

$ efi-readvar -v dbx | grep "List"

dbx: List 0, type SHA256

In order to understand what we are looking at, one should examine the dbx format. A signature database (of which dbx is an instance) internally represented as a concatenation of an arbitrary number of “signature lists”, i.e. EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST structures. Despite its name, a signature list usually does not store signatures (in the cryptographic sense); what it does store is determined by the value of itsSignatureType field. (Strictly speaking, it is not a list either, but rather an array, i.e. a continuous region of memory containing multiple equisized items).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct _EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST {

EFI_GUID SignatureType;

UINT32 SignatureListSize;

UINT32 SignatureHeaderSize;

UINT32 SignatureSize;

// UINT8 SignatureHeader [SignatureHeaderSize];

// EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA Signatures [__][SignatureSize];

} EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST;

In our case, it is EFI_CERT_SHA256_GUID (which efi-readvar shows as SHA256) identifying sha256 hashes of binaries. For contrast, take a look at db contents.

1

2

3

4

$ efi-readvar -v db | grep "List"

db: List 0, type X509

db: List 1, type X509

db: List 2, type X509

db’s value is comprised of three lists storing a X.509 certificate each (because certificates vary in length).

Going back to the subject of this study, we expect to find a sha256 hash value of Ubuntu bootloader in dbx. How would one go about verifying it? The first order of business is to locate the bootloader itself. Were we to deal with an operating system installed on the hard drive, efibootmgr --verbose, would give us the path.

INFO:

efibootmgr, in turn, consults UEFI variables named Boot\%04x (a number in hex with leading zeros prefixed by “Boot”) representing boot options. Interestingly, UEFI variables stored in NVRAM are mapped to virtual files in a pseudo file system and, that being the case, one can easily read them without specialized utilities. Thus, a quick and dirty way of extracting the paths would be something along the lines of:

#!/bin/bash

for file in /sys/firmware/efi/efivars/Boot[0-9,a-h,A-F][0-9,a-h,A-F][0-9,a-h,A-F][0-9,a-h,A-F]-8be4df61-93ca-11d2-aa0d-00e098032b8c ; do

echo "~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~"

strings -e l $file

doneIn case of a bootable thumbdrive, however, we should look for the default path; the latter is architecture-dependent and can be deduced from the CPU architecture based on the information given in the Removable Media Boot Behavior section of UEFI specification. Given the current PC market, chances are it would be /EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI (or, say, /EfI/bOOt/BooTx64.eFi since the boot partition must be FAT-formatted, which makes file names case-insensitive).

Having located the bootloader, we may now find out if it is listed in dbx or not: it turns out, UEFI executable images comply with PE32+ specification and, as such, bear signatures in Authenticode format. In addition to the signature format, Authenticode also establishes a procedure for computing binary’s digest whereby a signing utility determines which parts of the PE file are to be included in and which – omitted from the computation. As for the hashing algorithm, the options changed over time: initially only MD5 and SHA-1 were available, then SHA-2 was introduced and – effective from January of 2016 – enforced, leading to proliferation

of doubly-signed (to ensure backward compatibility) binaries. SHA-2 defines a family of hash functions varying in the length of resulting value: sha224, sha256, sha384, etc. Conveniently enough, in the case of BOOTx64.EFI, sha256 has been utilized, thus the resulting digest is what goes into dbx.

The python script below outputs an Authenticode digest stored in a header of the PE binary, a path to which is supplied as a command line argument.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

#for signify==0.3.0

#from signify.signed_pe import SignedPEFile

from signify.authenticode import SignedPEFile

import sys

if __name__ == "__main__":

with open(sys.argv[1], "rb") as fl:

pe = SignedPEFile(fl)

signed_data = list(pe.signed_datas)[0]

print(signed_data.spc_info.digest.hex())

This little script makes finding the BOOTx64.EFI’s hash in dbx a piece of cake.

1

2

$ efi-readvar -v dbx | grep $(python3 pe_sig_hash.py ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI)

Hash:007f4c95125713b112093e21663e2d23e3c1ae9ce4b5de0d58a297332336a2d8

Indeed, there is an entry corresponding to LiveCD bootloader in the UEFI revocation list, but the question remains: why is it there? What makes BOOTx64.EFI problematic? To answer this question let us turn to the relevant security advisory issue from Microsoft. Originally it was published to address the vulnerability in GRUB2 (GRand Unified Bootloader II) discovered by Jesse Michael and Mickey Shkatov and publicly disclosed in early 2020 (search for CVE-2020-10713). This vulnerability commonly goes by the name of “a hole in the boot” and consists in the possibility of a buffer overflow when attempting to parse a spurious configuration file (as described in great detail in the There is a Hole in the Boot whitepaper); the restriction (on sizes of their internal buffers) is posed by the flex/bison lexer/parser pair, that dutifully report the fact that the input string has exceeded the threshold, but this error is ignored upstream. “Microsoft is working to complete validation and compatibility testing of a required Windows Update that addresses this vulnerability,” the security advisory claimed. In the meantime, Canonical security team apparently decided to fix GRUB2 once and for all, subjecting the source code to rigorous scrutiny. As a result, a fair number of new vulnerabilities had been discovered; many of them have to do with the lack of necessary checks when performing memory allocation and other instances of buffer overflow; some use-after-free errors and errors related to improper hardware handling are in there, too. Sixteen issues in total were reported.

The delay also gave Linuxes of various flavours an opportunity to upgrade their bootloaders while they were still allowed to boot. Finally, on the 9th of August, this year, ADV200011 was updated to say “Microsoft has released standalone security update 5012170 to provide protection against the vulnerabilities described in this advisory.”

With all that said, one would expect the “forbidding” hash we found in dbx to be that of GRUB2; in reality, however, the situation is a bit more complicated: BOOTx64.EFI is not GRUB2 at all, but a small module (also known as a “shim”), whose only responsibility is to verify and launch a second-stage bootloader, in our case, GRUB2. This division of booting-related functionality into first and second-stage bootloaders is by no means new for in the past tight restrictions, chiefly on the size of code (which in its entirety must have fitted into the boot sector), were imposed on the module that started the operating system and it had to be split in two as a result. Where Ubuntu Live CD is concerned, the reasons behind such an arrangement are different, one of them being that Microsoft’s policy forbids signing any software subject to GPLv3 and this is exactly the license GRUB2 is distributed under. On account of this fact, GRUB2 binary is signed with a certificate from Canonical and the said certificate is stored (as data) in BOOTx64.EFI thereby allowing the shim (that, itself, is signed by Microsoft so that Secure Boot does not prevent it from running) to verify GRUB2’s cryptographic signature before transferring control.

NOTE: I designed an experiment aiming to demonstrate that the signature verification indeed took place, which resulted in this post and the fact that you are reading the article now and not in August, when I first encountered and solved the issue with booting from Live CD.

Now that we have the full picture, a trivial solution springs to mind: simply update Live CD to the latest version. Creature of habit, I decided to stick with Focal Fossa (on account of it being an LTS version), but at the time acquiring the latest .iso did not solve the problem for BOOTx64.EFI contained there had its hash in dbx as well (Focal Fossa has been updated once more since late August, when I was grappling with secure boot; checking if the new shim has not yet been revoked is left as an exercise for the most punctilious of my readers).

1

2

$ efi-readvar -v dbx | grep $(python3 pe_sig_hash.py ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI)

Hash:2ea4cb6a1f1eb1d3dce82d54fde26ded243ba3e18de7c6d211902a594fe56788

It is only when I upgraded to Jammy Jellyfish that Ubuntu booted with Secure Boot enabled.

In Place of Conclusion

We learned about the role Secure Boot plays in achieving operating systems’ security objectives, why a vulnerability in GRUB upsets this arrangement, thereby necessitating Ubuntu’s upgrade, and how this upgrade is forced by Windows in an attempt to eliminate the security threat.

At this point, whether to proceed with this two-part series is entirely the matter of being satisfied with the answer as given. On the one hand, we saw with our own eyes (or ears in case some text-to-voice implement, animate or technological, was employed) shim’s hash in dbx. On the other hand, if one is inclined to be pedantic, it is yet impossible to tell if the hash was not there before the update and that its introduction constituted the actual reason behind the boot “malfunction”. What we will do next is recover the previous state of dbx for comparison, figuring out how windows updates are structured and what lies inside update files for UEFI signature lists along the way. Interested? Then proceed here.

– Ry Auscitte

References

- KB5012170: Security update for Secure Boot DBX: August 9, 2022

- Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) Specification, Release 2.10

- Mathieu Trudel-Lapierre, How to sign things for Secure Boot

- Josh Boyer, Kevin Fenzi, Peter Jones, Josh Bressers, Florian Weimer, UEFI Secure Boot Guide, Fedora Draft Documentation

- Secure Boot and Trusted Boot, Windows Security, Microsoft Docs

- Peter Jones, The UEFI Security Databases, The Uncoöperative Organization Blog

- Windows Secure Boot Key Creation and Management Guidance, Desktop Manufacturing, Microsoft Docs

- James Bottomley, efitools

- Windows Authenticode Portable Executable Signature Format

- Jody Cloutier, Windows Enforcement of Authenticode Code Signing and Timestamping

- ADV200011: Microsoft Guidance for Addressing Security Feature Bypass in GRUB

- There is a Hole in the Boot, Eclypsium

- Kevin Tremblay, UEFI Signing Requirements, Microsoft Tech Community

- Ry Auscitte, First-Stage Bootloader: Hey, You’ve Got Pointy Ears Sticking out of Your Window (2022), Notes of an Innocent Bystander (with a Chainsaw in Hand)

- Ry Auscitte, Inner Workings of UEFI Secure Boot Signature Revocation List (DBX) Updates (2023), Notes of an Innocent Bystander (with a Chainsaw in Hand)