Inner Workings of UEFI Secure Boot Signature Revocation List (DBX) Updates

Introduction

This is the second article in a two-part series. Previously, we have established that an NVRAM variable called dbx contained a hash of Ubuntu’s first-stage bootloader, which, dbx representing a revocation list of modules that had been identified as posing a threat to the operating system security objective, resulted in Ubuntu live CD being prohibited from booting. Studious by nature (and, no doubt, only the most studious of my readers chose to stay for the second part), we are aiming to prove that it was the KB5012170 Windows update that placed the hash value in question into dbx.

How are we to approach the task at hand? The first idea that springs to mind is uninstalling the update to recover the previous dbx contents with the object of asserting that, unlike the most recent revocation list, it does not contain the hash. This solution, though easily implementable, is of no educational value whatsoever and, as such, will be discarded. Instead, we are going to procure the KB5012170’s setup file (i.e. update package), take it apart extracting the data that is to go into dbx, and see if it includes the Ubuntu’s bootloader hash.

Provided the plan sounds sufficiently interesting, let us proceed with no delay.

On the Anatomy of Windows Updates

The Update Package Structure

To begin with, I downloaded KB5012170 update package for the version of Windows used in the experiment from Microsoft Update Catalog. Despite the disguise of .msu extension, inside, it turned out to be an ordinary cabinet file, as evident from the file signature.

1

2

3

$ hexdump -C -n 4 windows10.0-kb5012170-x64.msu

00000000 4d 53 43 46 |MSCF|

00000004

Cabinet files are nothing more than digitally singed (which is optional) archives supporting lossless data compression.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ binwalk windows10.0-kb5012170-x64.msu

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 Microsoft Cabinet archive data, 259339 bytes, 4 files

259339 0x3F50B Object signature in DER format (PKCS header length: 4, sequence length: 9758

259546 0x3F5DA Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1278

260828 0x3FADC Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1648

263221 0x40435 Object signature in DER format (PKCS header length: 4, sequence length: 5876

263613 0x405BD Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1808

265425 0x40CD1 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1905

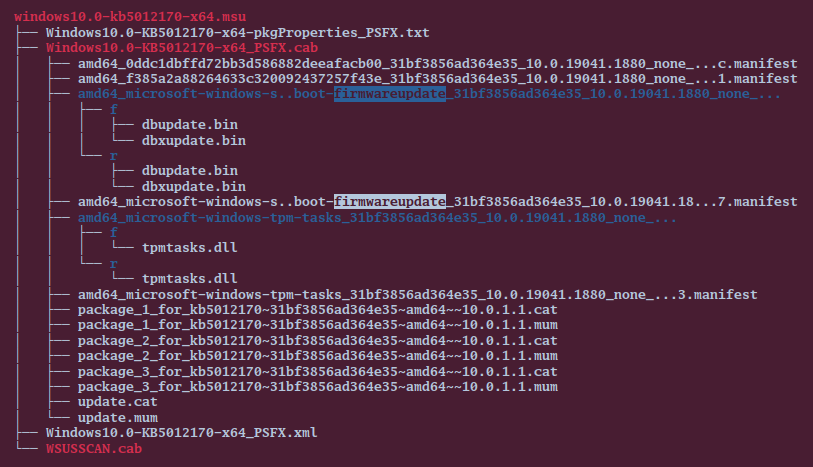

(by the way, notice that the archive is doubly-signed to ensue compatibility) The format being well-established, there is no shortage of tools for handling cabinet files; Ubuntu’s Archive Manager, for example, will do the trick. Hiding in the archive is another cabinet file – this time with the proper .cab extension – Windows10.0-KB5012170-x64_PSFX.cab. I went ahead and unpacked relevant files; the resulting tree structure is presented below.

Let us focus on the entries containing the string “firmwareupdate” in their names and ignore the rest. The first item that should capture our attention is a manifest file, presumably, providing the metadata describing how the update is to be carried out. In the manifest, one discovers a line or two that would merit investigation in their own right: for example, a mysterious tag <SecureBoot UpdateType="DbxOnly" /> – but what interests us is the following fragment:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

<file name="dbxupdate.bin"

destinationPath="$(runtime.system32)\SecureBootUpdates\"

sourceName="dbxupdate.bin" importPath="$(build.nttree)\"

sourcePath=".\">

<securityDescriptor name="WRP_FILE_DEFAULT_SDDL" />

<asmv2:hash xmlns:asmv2="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:asm.v2"

xmlns:dsig="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

<dsig:Transforms>

<dsig:Transform Algorithm="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:HashTransforms.Identity" />

</dsig:Transforms>

<dsig:DigestMethod Algorithm="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#sha256" />

<dsig:DigestValue>UlftZMySTmmlvwwOF9qD/RzOLIowjtvzkrluVmhhTqA=</dsig:DigestValue>

</asmv2:hash>

</file>

The reason why this particular fragment should spike our interest is the fact that Secure Boot Signature Revocation List (a.k.a. Forbidden Signature Database) maintained by UEFI forum comes in files named dbxupdate.bin (possibly, with a postfix signifying the target CPU architecture). (Thus, those of users tenacious enough to own their platforms – by enrolling PEK and KEK of their own – can download the revocation list and perform the update manually.) By good fortune, the XML tag above seems to describe a file with this very name, “dbxupdate.bin”; there is a fair chance that its format is the same, too.

So what does the said XML snippet tell us? Firstly, an update file for the dbx variable, dbxupdate.bin, is placed into the %windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates directory (presumably, before the variable’s value in NVRAM is modified) and, secondly, the resulting file should have a sha256 hash of UlftZMySTmmlvwwOF9qD/RzOLIowjtvzkrluVmhhTqA=. Somewhat unconventionally, instead of a hexadecimal representation, the string is a base64-encoded binary hash value.

NOTE: Reading from this directory on Linux is not without its problems.

For files that are not meant to be modified, Windows 10 introduced a data-compression mechanism, CompactOS, to save disk space, and dbxupdate.bin happens to be compressed in this manner. The way Windows implements CompactOS is by keeping the compressed data in an alternative stream (while the stream associated with the $Data attribute remains empty) and setting up a reparse point with a special tag, IO_REPARSE_TAG_WOF = 0x80000017 (which is reflected in the value of $REPARSE_POINT attribute). A file system filter driver is registered to process reparse data of this kind; it provides a decompressed file stream whenever a “read file” system call is invoked.

Depending on your Linux flavour and version, NTFS driver may not support some types of reparse points (IO_REPARSE_TAG_WOF in particular) by default.

$ ls -l ./Windows/System32/SecureBootUpdates

total 1

-rwxrwxrwx 3 * * 3 Dec 7 2019 dbupdate.bin

lrwxrwxrwx 3 * * 34 Aug 10 07:52 dbxupdate.bin -> 'unsupported reparse tag 0x80000017'The issue is easily circumvented by installing the

ntfs-3g-system-compression plugin. It comes with comprehensive compilation instructions listing all the packages to be installed (in addition to build-essentials), hence building it should present no problem, apart from the possibility of the plugin installation script not putting the binaries where NTFS driver expects to find them. The latter is fixable, however, following the steps suggested by Jean-Pierre André here.

$ ls /usr/local/lib/ntfs-3g

ntfs-plugin-80000017.la ntfs-plugin-80000017.so

$ strings `which ntfs-3g` | grep ntfs-plugin

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ntfs-3g/ntfs-plugin-%08lx.so

$ ls /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ntfs-3g

ls: cannot access '/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ntfs-3g': No such file or directory

$ sudo mkdir /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ntfs-3g

$ sudo cp /usr/local/lib/ntfs-3g/* /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ntfs-3gNow that we have found the data file Windows used to update dbx, parsing it in search of Ubuntu bootloader’s hash would appear to be the only remaining step. The file format specification publicly available, we will look though dbxupdate.bin, locate the hash, and we are home free, right? Well, no. We don’t call ourselves studious for nothing! :-D Take another look at the prototype of SetVariable(), a function defined in UEFI and intended to set values of NVRAM variables.

1

2

3

4

5

EFI_STATUS SetVariable(IN CHAR16* VariableName,

IN EFI_GUID* VendorGuid,

IN UINT32 Attributes,

IN UINTN DataSize,

IN VOID* Data);

The function parameter Attributes holds an OR-combination of various flags. Among them is EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE, an attribute determining whether the data passed to the function in the Data parameter rewrites the existing variable value or is appended to it. In case of the former, presence of a hash in the update file does not guarantee it is this hash that is being added.

Unfortunately, whether Microsoft chose to call SetVariable() with EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE set, thereby making the dbx updates incremental, or not is something we do not know yet.

This turn of events considered, the fact that a copy of dbxupdate.bin remains on disk is good news for getting hold of the previous version of dbxupdate.bin may help in our pursuit. If the previous version of dbx update file does not contain a hash value, while the latest one does, then we can safely assume that, irrespective of whether the EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE flag was set, the latest update intended to add the value in question. To this end, I checked Volume Shadow Snapshots for old files in %windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates.

NOTE: Based on my experience, I would recommend libvshadow for browsing Windows VSS on Linux on account of the library having proved functional and stable.

Differential Updates

An earlier “shadow” copy of SecureBootUpdates would have made my life a breeze. Alas! The computer I used did not have one. We will have to get back to it later; for now, let us switch gears and consider the second discovery. Why would the manifest need to specify dbxupdate.bin’s hash? It is files that are either generated or downloaded separately that need to be checked for errors. Does a fresh copy of dbxupdate.bin come along with the update .cab? It turns out, it does not (though, file hashes happens to be a standard feature of manifest files not connected to the update technology); rather, dbxupdate.bin is generated based on an old version of the same, already resident on user’s computer, and one or more small differentials (delta files), arriving as part of the update; a so-called differential compression technique is applied to pre-compute the deltas and then decompress the target file on site. For details, I refer the reader to Microsoft’s white paper, which is concise enough so as to constitute little to no distraction from the main narrative. Please, go ahead and at least skim though the material.

To recap the white paper, in case an old version of the file being updated is on the computer, residing alongside it, one will find a reverse differential (stored in the folder named ./r), a delta file that, when applied to the file already on the PC, produces a base version thereof, while the update package will contain a forward differential (arriving in the folder named ./f), which is then applied to the reconstructed base version in order to obtain the end result. By a base version, Microsoft means either the file contained in the latest major OS release or an RTM version. The resulting, updated, file along with the reverse and forward differentials are saved in %windir%\WinSxS.

The latter sounds promising since it suggests the possibility that the dbxupdate.bin file involved in the previous update of dbx might have been stored in WinSxS. Sure enough, I found two folders pertaining to the updates of this kind: one with dbxupdate.bin for KB5012170, compete with the differentials identical to those contained in the package downloaded from Microsoft Update Catalog, and another – for some earlier update. It only had dbxupdate.bin inside (no ./r, ./f or ./n for that matter), thus, I assume, to deploy it, a method other than differential compression was utilized.

Now that we, ostensibly, have a previous version of dbxupdate.bin at our disposal, we would do well to verify that applying the differentials to it in the order prescribed by the white paper results in dbxupdate.bin identical to that in SecureBootUpdates. In order to find a tool that would perform “differential decompression” for us, we must first identify the file format.

1

2

3

$ hexdump -n 16 -C ./KB5012170/u/f/dbxupdate.bin

00000000 b4 4b 01 63 50 41 33 30 a6 30 83 3b 8d 95 d8 01 |.K.cPA30.0.;....|

00000010

The PA30 signature leads us to another excellent resource on recent developments in Windows update technology – this post by Jaime Geiger. It offers helpful insights into specifics of Windows update operation and format of update patches, but, more importantly, provides a python script to apply the differentials. However, the script uses Microsoft Delta Compression API and, for this reason, it is only usable under Windows. So into the land of Windows we go. Get your canes (or broomsticks, to each her own) ready.

You will find dealing with cabinet files in Windows equally painless: simply use the expand -f:* <path to .cab> <output directory> command. Since there is no accompanying reverse differential, we will treat the oldest of the two dbxupdate.bin files residing in WinSxS as base.

1

2

3

> python delta_patch.py -i %windir%\WinSxS\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1_none_6ab72e7ea4dfef1b\dbxupdate.bin -d .\KB5012170\u\f\dbxupdate.bin

Applied 1 patch successfully

Final hash: UlftZMySTmmlvwwOF9qD/RzOLIowjtvzkrluVmhhTqA=

Notice that the resulting sha256 hash matches the one specified in the manifest.

NOTE:

What is more, the fact that the script completed successfully, in itself, speaks in favor of our guess being correct since the Delta Compression API seems to be equipped with a safeguard against improper application of differentials. Pass a wrong (i.e. computed for a file other than the one in the input buffer) differential to ApplyDeltaB() and, in all probability, the function will fail, with GetLastError() returning 13 (which translates into the “The data is invalid” message).

The remaining two sections could be skipped upon the first reading. Those of my readers who believe their lives are too short for dull long-winded explanations are welcome to continue with the study at this section.

An Assembly for The Secure Boot Variables Update

It all worked out rather well, will you not agree? A quick two-minute search over the WinSxS directory results in almost (differential updates have been adopted relatively recently) entire update history for a file. But why spend two minutes running a search, when one can automate the task in under 24 hours? Right? Thus, I wrote a python script that, given a file name, would traverse the WinSxS directory collecting all the relevant paths and establishing relations between multiple versions of the given file (implementation notes can be found here). Here is the output my script produces for dbxupdate.bin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

>python win_read_winsxs.py -f dbxupdate.bin

microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate (arch = amd64, locale = none)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate

files: {'dbupdate.bin', 'dbxupdate.bin'}

fwd: set()

rev: set()

null: set()

arch: amd64

ver: 10.0.19041.1

ts: Sat Dec 7 01:31:06 2019

loc: none

token: 31bf3856ad364e35

hash: 6ab72e7ea4dfef1b

microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate

files: {'dbupdate.bin', 'dbxupdate.bin'}

fwd: {'dbxupdate.bin'}

rev: {'dbxupdate.bin'}

null: set()

arch: amd64

ver: 10.0.19041.1880

ts: Wed Aug 10 00:52:54 2022

loc: none

token: 31bf3856ad364e35

hash: 294d9e3cbae1ff57

dbxupdate.bin: 10.0.19041.1○ ==> 10.0.19041.1880

dbxupdate.bin has been discovered to belong to the amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_none assembly (assembly in the broadest sense of the word for it does not contain executable images); of this assembly, there are two versions currently available in WinSxS: 10.0.19041.1, identified as a base version (of which we are informed by the ο symbol), and 10.0.19041.1880, that can be derived from the base version by the way of applying a forward differential (as indicated by the “==>” sign).

As mentioned before, the dbxupdate.bin file stored as part of the most recent revision (1880) of the assembly is identical to that found in %windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>certutil -hashfile %windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates\dbxupdate.bin MD5

MD5 hash of C:\WINDOWS\System32\SecureBootUpdates\dbxupdate.bin:

·8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2·

CertUtil: -hashfile command completed successfully.

>certutil -hashfile %windir%\WinSxS\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1880_none_294d9e3cbae1ff57\dbxupdate.bin MD5

MD5 hash of C:\WINDOWS\WinSxS\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1880_none_294d9e3cbae1ff57\dbxupdate.bin:

·8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2·

CertUtil: -hashfile command completed successfully.

Furthermore, the differential files residing in the assembly’s .\r and .\f subdirectories are exactly the same as those that arrived in the update .cab (you will have to take my word for it since I have chosen to spare you a rather long-winded certutil output). Also, notice that the directory (inside the update package; see the update tree structure at the very beginning of the section) containing the differentials bears the same name as the assembly, amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1880_none_294d9e3cbae1ff57.

Taking everything into account, one can come up with an approximate sequence of steps involved in installing the KB5012170 update:

- The installer unpacks the update archive and identifies the assembly name by examining the manifest.

- The installer locates the most recent version of

amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_nonecurrently on the computer, 10.0.19041.1. - Seeing that it is a base version, no reverse differential is necessary (neither is it present, for that matter).

- Applying a forward differential from the update .cab, the installer reconstructs a new version of

dbxupdate.bin. - The newly generated

dbxupdate.bin, along with the forward differential used to obtain it and a reverse differential necessary for future updates are copied to WinSxS under a directory namedamd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1880_none_294d9e3cbae1ff57. - The installer copies

dbxupdate.binto%windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates, modifies the registry as instructed by the manifest, and initiates an update of the NVRAM variable.

This is the working hypothesis. What took place in reality, only the kernel almighty knows, but the net result is that we have at our disposal the latest and the previous versions of dbxupdate.bin… Or do we? The forward differential being applied to the base rather than the latest available version, theoretically, nothing prevents the possibility of another update (of which our “testing grounds” system for some reason bears no record) “squeezing in” between the deployment of the 10.0.19041.1 and 10.0.19041.1880 assemblies.

An Extra Check for Better Sleep

The possibility is far fetched, I will be the first one to admit, but, to be on the safe side, I searched for other dbx-related Window updates released between 2019-12-07 and 2022-08-10 (see the timestamps in the output of python win_read_winsxs.py). Two updates only met the criteria: KB4575994 and KB4535680. The former one was discarded right away due to the lack of automation: Microsoft offers no .msu file for this update; instead, users are suggested to download the latest dbxupdate.bin from the uefi.org and invoke a Power Shell script in order to install it. It would be extremely out of character for a person who owns this computer to partake in so precarious an enterprise ;-) I vouch for her. Thus, we are left with the update labeled KB4535680 as the only contender.

Even with this, rather welcome, reduction in the number of updates to check, the challenges were not over. The update log did not go far back enough for me to determine if and when the update in question was installed and what the Windows version was at that time, so I downloaded all available .msu files for the Windows edition I was working with. Of these, two had declared in their manifests the same target hashes as that of dbxupdate.bin version 10.0.19041.1 (the remaining three specified a different value). Moreover, in spite of the fact that the update was dated January 12, 2021, the files inside were much older, older, in fact, than dbxupdate.bin, ver. 10.0.19041.1, according to its “last modified” timestamp (2019-12-07). For example,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

$ ls ./KB4535680/u -R -l

./KB4535680/u:

total 8

drwxrwxr-x 2 * * 4096 Sep 8 15:55 f

drwxrwxr-x 2 * * 4096 Sep 8 15:55 r

./KB4535680/u/f:

total 8

-rw-rw-r-- 1 * * 46 ·Sep 23 2019· dbupdate.bin

-rw-rw-r-- 1 * * 1368 ·Sep 23 2019· dbxupdate.bin

./KB4535680/u/r:

total 8

-rw-rw-r-- 1 * * 46 ·Sep 23 2019· dbupdate.bin

-rw-rw-r-- 1 * * 2840 ·Sep 23 2019· dbxupdate.bin

Its respectable age had also been betrayed by the assembly versions the update was to install: 10.0.17763.793, 10.0.18362.411, 10.0.14393.3001, 10.0.10240.18575, and 10.0.17134.1060 – all of it leading me to the conclusion that KB4535680 could not have been deployed after the amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1_none_6ab72e7ea4dfef1b assembly was.

NOTE: Of course, this rather tedious way of establishing the exact update sequence is something this study could easily do without; the real reason for going into such depths was to bring to the reader’s attention some idiosyncrasies of Windows updates they may encounter.

Only now do I claim with a fair degree of confidence that I have in my possession two consecutive versions of dbxupdate.bin.

A Peek Inside the DBX Update

All the necessary versions of dbxupdate.bin secured, how are we to go about comparing them? A cursory glance at the hexdump output reveals that both files are binary, and so the hope is that they comply with the same format as their namesakes found on UEFI forum’s website. It is quite rare that reality lives up to our expectations; in this case, however, we discover that, for once, not only does it meet the expectations, but exceeds them :-) for the dbxupdate.bin installed by KB5012170 is identical to that most recently published by the Forum.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>certutil -hashfile .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2022-08-12.bin MD5

MD5 hash of .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2022-08-12.bin:

·8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2·

CertUtil: -hashfile command completed successfully.

>certutil -hashfile %windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates\dbxupdate.bin MD5

MD5 hash of C:\WINDOWS\System32\SecureBootUpdates\dbxupdate.bin:

·8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2·

CertUtil: -hashfile command completed successfully.

As a result, we can safely rely on the ready-made utilities to handle the files and, if none suits us, consult the publicly available specification while implementing our own.

NOTE:

For those who are keeping score, the same dbxupdate.bin file has turned up at four different locations:

- Among the files generated by applying the KB5012170 update.

%windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates.- In

%windir%\WinSxS\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1880_none_294d9e3cbae1ff57. - On UEFI Forum site (as of August of 2022, it is the latest revocation list there).

A Quick Tour of the Data Structures

What we need is a parser that would dump the structures stored inside the dbxupdate.binfile in a human-readable text format, but before we set out on the quest of procuring one, let us familiarize ourselves with the said data structures. Apart from the specification, I would recommend this blog post by Peter Jones as an easy-to-follow guide to the revocation list updates file format.

Secure Boot dictates that dbx be a so-called authenticated variable meaning that whenever its new value is passed to the SetVariable function, it is always prefixed by an authentication structure; which one is determined by the attributes of the variable. On Linux, dbx’s attribute bitmask is stored in the first four bytes of the /sys/firmware/efi/efivars/dbx-d719b2cb-3d3a-4596-a3bc-dad00e67656f file. I went ahead and extracted the flags:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

>>> with open("/sys/firmware/efi/efivars/dbx-d719b2cb-3d3a-4596-a3bc-dad00e67656f", "rb") as f:

... attrs = int.from_bytes(f.read(4), byteorder = "little")

...

>>> ad = { 0x1 : "EFI_VARIABLE_NON_VOLATILE", 0x2 : "EFI_VARIABLE_BOOTSERVICE_ACCESS",

... 0x4 : "EFI_VARIABLE_RUNTIME_ACCESS", 0x8 : "EFI_VARIABLE_HARDWARE_ERROR_RECORD",

... 0x10 : "EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATED_WRITE_ACCESS", 0x20 : "EFI_VARIABLE_TIME_BASED_AUTHENTICATED_WRITE_ACCESS",

... 0x40 : "EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE", 0x80 : "EFI_VARIABLE_ENHANCED_AUTHENTICATED_ACCESS" }

>>> print(*[ ad[ ((1 << s) & attrs) ] for s in range(0, 32) if (attrs & (1 << s) ) != 0 ], sep = "\n")

EFI_VARIABLE_NON_VOLATILE

EFI_VARIABLE_BOOTSERVICE_ACCESS

EFI_VARIABLE_RUNTIME_ACCESS

EFI_VARIABLE_TIME_BASED_AUTHENTICATED_WRITE_ACCESS

There you have it: dbx persists across reboots, is accessible in both, preboot and runtime (i.e. after the OS boots), environments, and, most importantly, is authenticated with the contents of an EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2 structure. The update file is, therefore, organized as follows:

1

EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2 (EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST*)

i.e. an instance of EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2 followed by zero (deletes the variable) or more EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST instances.

Let us examine the structures one by one. EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2 contains a time stamp (which will be omitted from the discussion) and authentication information.

1

2

3

4

typedef struct {

EFI_TIME TimeStamp;

WIN_CERTIFICATE_UEFI_GUID AuthInfo;

} EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2;

Having found the definition of WIN_CERTIFICATE_UEFI_GUID given in the specification slightly confusing, I came up with another, fields-wise equivalent, layout of the structure, based on Peter Jones’ helpful explanation. Here it is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

typedef struct _WIN_CERTIFICATE_UEFI_GUID {

UINT32 dwLength;

UINT16 wRevision;

UINT16 wCertificateType;

EFI_GUID CertType;

//UINT8 CertData[dwLength - sizeof(UINT32) - 2 * sizeof(UINT16) - sizeof(EFI_GUID)];

} WIN_CERTIFICATE_UEFI_GUID;

When WIN_CERTIFICATE_UEFI_GUID is embedded into EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2, wCertificateType is set to WIN_CERT_TYPE_EFI_GUID, CertType – initialized to EFI_CERT_TYPE_PKCS7_GUID, and CertData contains DER-encoded SignedData structure from PKCS#7 version 1.5 (RFC 2315). The latter defined in a standard, there are plenty of libraries to parse it. The data being signed consists of VariableName, VendorGuid, and Attributes parameter values (as passed to SetVariable()), augmented by the contents of EFI_VARIABLE_AUTHENTICATION_2::TimeStamp and all the EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST instances concatenated.

Speaking of EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST, its definition is presented below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

typedef struct _EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA {

EFI_GUID SignatureOwner;

//UINT8 SignatureData[ (EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST*)parent->SignatureSize -

// sizeof(GUID) ];

} EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA;

typedef struct _EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST {

EFI_GUID SignatureType;

UINT32 SignatureListSize;

UINT32 SignatureHeaderSize;

UINT32 SignatureSize;

//UINT8 SignatureHeader[SignatureHeaderSize];

//EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA Signatures[ (SignatureListSize - sizeof(EFI_GUID) -

// 3 * sizeof(UINT32) - SignatureHeaderSize) /

// SignatureSize ];

} EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST;

Despite the name, an instance of EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST is, technically, not a list, by an array of equisized EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA structures prefixed by a (28 + SignatureHeaderSize)-byte header. For this reason, there need be multiple instances of EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST, one per value of the (SignatureType, SignatureSize) tuple, in the update file and whenever an update file includes X.509 certificates, as a rule, each is placed in a separate signature list (since X.509 certificates differ in length). SignatureType determines how signature header is interpreted and its size as well as format of EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA::SignatureData.

EFI_SIGNATURE_DATA::SignatureOwner identifies the agent who added the signature.

UEFI defines an impressive variety of ways to identify the entity being revoked. Listed below are all possible values of SignatureType (so that the reader may share in the fascination).

EFI_CERT_SHA256_GUID: a sha256 hashEFI_CERT_RSA2048_GUID: an rsa2048 keyEFI_CERT_RSA2048_SHA256_GUID: an rsa2048 signature of a sha256 hashEFI_CERT_SHA1_GUID: a sha1 hashEFI_CERT_RSA2048_SHA1_GUID: an rsa2048 signature of a sha1 hashEFI_CERT_X509_GUID: a DER-encoded X.509 certificateEFI_CERT_SHA224_GUID: a sha224 hashEFI_CERT_SHA384_GUID: a sha384 hashEFI_CERT_SHA512_GUID: a sha512 hashEFI_CERT_X509_SHA256_GUID: a sha256 hash of an X.509 certificate

In practice, I came across two types of revocation list entries only: EFI_CERT_SHA256_GUID, a sha256 hash of a UEFI executable where a vulnerability had been found, and EFI_CERT_X509_GUID, a DER-encoded X.509 certificate that had been either used to sign (a family of) faulty UEFI modules or compromised in some other way.

On this note, I am concluding this hasty overview of dbx update files organization; whatever structure definitions I might have missed, can easily be found in the UEFI specification.

Inside dbxupdate.bin

Naturally, readers should feel free to use a dbx update parser of their choosing; I, however, decided to implement my own for the occasion since, where reverse-engineering matters are concerned, hands-on experience is by far the best way of learning. Besides, my parser is written in python, a universal language everyone speaks.

My script accepts paths to dbxupdate.bin and a (optional) DER-encoded certificate to be used as a root when the chain of trust involved in authenticating the update is constructed. For the script to work correctly, it must be a certificate stored in KEK. Here is the output this script produces for KB5012170.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

>python dbxupdate_parser.py %windir%\System32\SecureBootUpdates\dbxupdate.bin MicCorKEKCA2011_2011-06-24.crt

Container:

Auth2 = Container:

TimeStamp = ·2010-03-06 19:17:21+00:00·

AuthInfo = Container:

dwLength = 3318

wRevision = 512

wCertificateType = (enum) WIN_CERT_TYPE_EFI_GUID 3825

CertType = u'{4aafd29d-68df-49ee-a98a-347d375665a7}' (total 38)

CertData = ListContainer:

Container:

C/N = u'·Microsoft Corporation KEK CA 2011·' (total 33)

S/N = 1137338005320235767164219581974198572443238437

Fingerprint = u'·c6c68c9bd883e14469c725251201043fb7d4c3cd·' (total 40)

·Chain· = ListContainer:

Container:

C/N = u'Microsoft Corporation KEK CA 2011' (total 33)

S/N = 458269114596843440832515

Fingerprint = u'·31590bfd89c9d74ed087dfac66334b3931254b30·' (total 40)

Valid = u'2011-06-24 20:41:29+00:00 - 2026-06-24 20:51:29+00:00' (total 53)

Container:

C/N = u'Microsoft Windows UEFI Key Exchange Key' (total 39)

S/N = 1137338005320235767164219581974198572443238437

Fingerprint = u'c6c68c9bd883e14469c725251201043fb7d4c3cd' (total 40)

Valid = u'2021-09-02 18:24:31+00:00 - 2022-09-01 18:24:31+00:00' (total 53)

SignatureLists = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureType = u'{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}' (total 38)

SignatureListSize = 10444

SignatureHeaderSize = 0

SignatureSize = 48

SignatureHeader = b'' (total 0)

Signatures = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'80b4d96931bf0d02fd91a61e19d14f1da452e66db2408ca8604d411f92659f0a' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'f52f83a3fa9cfbd6920f722824dbe4034534d25b8507246b3b957dac6e1bce7a' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'c5d9d8a186e2c82d09afaa2a6f7f2e73870d3e64f72c4e08ef67796a840f0fbd' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'1aec84b84b6c65a51220a9be7181965230210d62d6d33c48999c6b295a2b0a06' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'c3a99a460da464a057c3586d83cef5f4ae08b7103979ed8932742df0ed530c66' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'58fb941aef95a25943b3fb5f2510a0df3fe44c58c95e0ab80487297568ab9771' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'5391c3a2fb112102a6aa1edc25ae77e19f5d6f09cd09eeb2509922bfcd5992ea' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'd626157e1d6a718bc124ab8da27cbb65072ca03a7b6b257dbdcbbd60f65ef3d1' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'd063ec28f67eba53f1642dbf7dff33c6a32add869f6013fe162e2c32f1cbe56d' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'29c6eb52b43c3aa18b2cd8ed6ea8607cef3cfae1bafe1165755cf2e614844a44' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'90fbe70e69d633408d3e170c6832dbb2d209e0272527dfb63d49d29572a6f44c' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'106faceacfecfd4e303b74f480a08098e2d0802b936f8ec774ce21f31686689c' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'174e3a0b5b43c6a607bbd3404f05341e3dcf396267ce94f8b50e2e23a9da920c' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'2b99cf26422e92fe365fbf4bc30d27086c9ee14b7a6fff44fb2f6b9001699939' (total 64)

[...]

Commenting the dump line by line would be an undertaking ludicrous beyond imagination, so, instead, I will only list a few points of interest. First of all, the update, judging by the timestamp, appears to be rather… dated. In fact, the timestamp is initialized to a particular value, the same in all the dbx update files (from Microsoft and UEFI Forum alike) I could get my hands on. Here is what the UEFI specification has to say on the subject: “In certain environments a reliable time source may not be available. In this case, an implementation may still add values to an authenticated variable since the EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE attribute, when set, disables timestamp verification.”

Second of all, one must pay attention when interpreting PKCS#7 SignedData stored in Auth2.AuthInfo.CertData. Notice that the common name of the signing entity is indicated as Microsoft Corporation KEK CA 2011, but the fingerprint that follows does not match that of the actual certificate.

1

2

$ openssl x509 -in MicCorKEKCA2011_2011-06-24.crt --fingerprint -noout

SHA1 Fingerprint=31:59:0B:FD:89:C9:D7:4E:D0:87:DF:AC:66:33:4B:39:31:25:4B:30

The discrepancy is explained by the fact that this data is obtained by parsing the signerInfos field of SignedData, where the signer’s certificate is specified by the “issuer distinguished name” (see RFC2315). To understand what is happening here, one must turn to the X.509 certificates that also come embedded in SignedData; the certificates field is what the script relies on when building a chain of trust. Upon examining CertData.Chain, it becomes clear that the new dbx value is signed with a certificate bearing a common name of Microsoft Windows UEFI Key Exchange Key (its fingerprint computing to c6:c6:8c:9b:d8:83:e1:44:69:c7:25:25:12:01:04:3f:b7:d4:c3:cd) and this certificate chains to Microsoft Corporation KEK CA 2011.

Finally, this update file contains one signature list only; its entries are all sha256 hashes as indicated by the value of SignatureType, which is equal to {c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328} (EFI_CERT_SHA256_GUID). The only other type of signatures I encountered “in the wild” is {a5c059a1-94e4-4aa7-b587-ab155c2bf072} (EFI_CERT_X509_GUID). Below is a dump of such a dbx update file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

>python dbxupdate_parser.py .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-10-12.bin

Container:

Auth2 = Container:

TimeStamp = 2010-03-06 19:17:21+00:00

AuthInfo = Container:

dwLength = 3329

wRevision = 512

wCertificateType = (enum) WIN_CERT_TYPE_EFI_GUID 3825

CertType = u'{4aafd29d-68df-49ee-a98a-347d375665a7}' (total 38)

CertData = ListContainer:

Container:

C/N = u'Microsoft Corporation KEK CA 2011' (total 33)

S/N = 1137338005291744326421988539423191331766272032

Fingerprint = u'3caa302c313cf27aa40e13414b0f15c60aa515ab' (total 40)

Chain = None

SignatureLists = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureType = u'{a5c059a1-94e4-4aa7-b587-ab155c2bf072}' (total 38)

SignatureListSize = 1104

SignatureHeaderSize = 0

SignatureSize = 1076

SignatureHeader = b'' (total 0)

Signatures = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = Container:

C/N = u'Canonical Ltd. Secure Boot Signing' (total 34)

S/N = 1

Fingerprint = u'594ece20591648f5a00de30cf61d118dbece8072' (total 40)

Valid = u'2012-04-12 11:39:08+00:00 - 2042-04-11 11:39:08+00:00' (total 53)

Container:

SignatureType = u'{a5c059a1-94e4-4aa7-b587-ab155c2bf072}' (total 38)

SignatureListSize = 1208

SignatureHeaderSize = 0

SignatureSize = 1180

SignatureHeader = b'' (total 0)

Signatures = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = Container:

C/N = u'Virtual UEFI SubCA' (total 18)

S/N = 241841431539745444034

Fingerprint = u'5e4e7344360047eb18cb0fbeaef93e78a51d5cfc' (total 40)

Valid = u'2018-04-03 17:47:34+00:00 - 2099-04-03 16:19:30+00:00' (total 53)

Container:

SignatureType = u'{a5c059a1-94e4-4aa7-b587-ab155c2bf072}' (total 38)

SignatureListSize = 812

SignatureHeaderSize = 0

SignatureSize = 784

SignatureHeader = b'' (total 0)

Signatures = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = Container:

C/N = u'Debian Secure Boot Signer' (total 25)

S/N = 2806418927

Fingerprint = u'8da5a198f2e8b27d0d51d0b4d73421525ba8df5d' (total 40)

Valid = u'2016-08-16 18:22:50+00:00 - 2026-08-16 18:22:50+00:00' (total 53)

Container:

SignatureType = u'{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}' (total 38)

SignatureListSize = 8812

SignatureHeaderSize = 0

SignatureSize = 48

SignatureHeader = b'' (total 0)

Signatures = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'80b4d96931bf0d02fd91a61e19d14f1da452e66db2408ca8604d411f92659f0a' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'f52f83a3fa9cfbd6920f722824dbe4034534d25b8507246b3b957dac6e1bce7a' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'c5d9d8a186e2c82d09afaa2a6f7f2e73870d3e64f72c4e08ef67796a840f0fbd' (total 64)

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{77fa9abd-0359-4d32-60bd-28f4e78f784b}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'1aec84b84b6c65a51220a9be7181965230210d62d6d33c48999c6b295a2b0a06' (total 64)

[...]

Take a note of the way certificates are stored, each in is own signature list with the value of SignatureSize set to the certificate length (plus sizeof(GUID)).

The Proof

All the forewords, introductions, and groundwork out of the way, we can finally get to what we have set out to do in the first place, which is to prove that it was the KB5012170 Windows update that placed a hash of BOOTx64.EFI, Ubuntu’s first stage bootloder, into dbx. As a reminder, I am restating the assumption we are working under: “If the previous version of dbx update file does not contain a hash value, while the latest one does, then we can safely assume that, irrespective of whether the EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE flag was set, the latest update intended to add the value in question.” Of course, this assumption would break if the attributes passed to SetVariable() changed from one update to another, but it is unlikely to be the case.

Let us first find out what hash value to look for.

1

2

$ python3 pe_sig_hash.py ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI

007f4c95125713b112093e21663e2d23e3c1ae9ce4b5de0d58a297332336a2d8

Why not try our hand at checking an update file for hashes using the newly implemented parser? I deemed it more convenient to run it within a python interpreter rather than as a script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>> from dbxupdate_parser import DbxUpdate

>>> import os

>>> upd = DbxUpdate(os.path.expandvars("%windir%\\System32\\SecureBootUpdates\\dbxupdate.bin"), None)

>>> len(upd.upd.SignatureLists)

1

>>> #There is one signature list only in the update file; it holds hashes

>>> upd_hashes = { s.SignatureData for s in upd.upd.SignatureLists[0].Signatures }

>>> "007f4c95125713b112093e21663e2d23e3c1ae9ce4b5de0d58a297332336a2d8" in upd_hashes

True

As expected, the latest dbxupdate.bin contains BOOTx64.EFI’s hash. What about dbxupdate.bin from the previous Windows update?

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> upd_prev = DbxUpdate(os.path.expandvars("%windir%\\WinSxS\\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1_none_6ab72e7ea4dfef1b\\dbxupdate.bin"), None)

>>> len(upd_prev.upd.SignatureLists)

1

>>> upd_prev_hashes = { s.SignatureData for s in upd_prev.upd.SignatureLists[0].Signatures }

>>> "007f4c95125713b112093e21663e2d23e3c1ae9ce4b5de0d58a297332336a2d8" in upd_prev_hashes

False

This time we do not find BOOTx64.EFI’s hash value in the signature list. Q.E.D.

Unplanned Experiments and Serendipitous Discoveries

Well, the previous section went by fast. Do not know about you, but to me, the culmination, the proof we had been working towards all this time, seemed a bit anticlimactic. So much effort was put in: studying Secure Boot PKI, dissecting Windows updates, figuring out the update file format, and even implementing a parser, and for what? For something so trivial as determining if both files contain a single miserable string of bytes?

I tell you what, why do we not conduct a few more simple experiments using the parser just developed, solve a mystery or two whilst gaining valuable insights into dbx updates? Are you in?

The first question in our agenda arises owing to one of our earlier observations. We have discovered that dbxupdate.bin arriving with the latest Windows update is identical to the same most recently released by UEFI forum. Are all updates to dbx issued by Microsoft mere copies of fruits of UEFI forum’s labor? To answer this question, we must get our hands on dbxupdate.bins extracted from other Windows updates and these files are not easy to come by. This is when Winbindex developed by Michael Maltsev comes to the rescue. Winbindex provides various versions of executable files (.exe, .dll, and .sys) that constitute Windows operating system; thus, one can download the entire update history of say, kernel32.dll beginning from the one found in Windows 10, release 1507, through all Windows updates and releases, up to the latest version (a functionality indispensable for systems and security researches). Where non-executable files are concerned, the capabilities are limited, however; at the time of writing, available for dbxupdate.bin is only meta-data, describing the files (hashes, sizes, and Windows versions), not the files themselves, and only base versions of dbxupdate.bin are included. Here is the data, albeit greatly edited down to save space.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

{

"fileInfo": {

"md5": "·45ac4530ada617e443e343c730a14dfe·",

"sha1": "3a2d8ecf4649b7d766b6579fc7044b3ba9bdf3a8",

"sha256": "528728c4a643d366445d953c6357a45656795396c09ac93b8a984b74c4bda9c3",

"size": 4961

},

"windowsVersions": {

"11-21H2": {

"BASE": {

"sourcePaths": [

"Windows\\System32\\SecureBootUpdates\\dbxupdate.bin"

],

"windowsVersionInfo": {

"isoSha256": "667bd113a4deb717bc49251e7bdc9f09c2db4577481ddfbce376436beb9d1d2f",

"releaseDate": "2021-10-04"

}

}

},

[...]

}

}

{

"fileInfo": {

"md5": "·0d157dba3d91f8f5a12b39d68d9b4358·",

"sha1": "8d46cc1cd3c3f1729bab6c97b856a9e94da0acb6",

"sha256": "0a15d385e02757ac103e51f52db5e2bdd3c83b60d8337a9c2ae74fbdb303dd9b",

"size": 7085

},

"windowsVersions": {

"1607": {

"BASE": {

"sourcePaths": [

"Windows\\System32\\SecureBootUpdates\\dbxupdate.bin"

],

"windowsVersionInfo": {

"isoSha256": "a01d0ce50c4c91964dfae08a5590a1d8e2a445cd80bb26eea4fee0f90198231a",

"releaseDate": "2016-08-02"

}

}

},

[...]

}

}

{

"fileInfo": {

"md5": "·9275304214f847b261c64e599092c265·",

"sha1": "dfa0e7d8d342f460042986a130c360eab2b47009",

"sha256": "a1fcafe3ce43172688ab6410140f704c0dfdbed3bf17c1b6ca59021fd979fa97",

"size": 4011

},

"windowsVersions": {

"1507": {

"BASE": {

"sourcePaths": [

"Windows\\System32\\SecureBootUpdates\\dbxupdate.bin"

],

"windowsVersionInfo": {

"isoSha256": "dee793b38ce4cd37f32847605776b0f91d8a30703dfc5844731b00f1171a36ff",

"releaseDate": "2015-07-29"

}

}

},

"1511": {

"BASE": {

"sourcePaths": [

"Windows\\System32\\SecureBootUpdates\\dbxupdate.bin"

],

"windowsVersionInfo": {

"isoSha256": "7536d3807a3ea388b90e4f26e14595ec80b77c07802dc7e979422ed4fcee9c7f",

"releaseDate": "2015-11-10"

}

}

}

}

}

We have hashes of all the base versions of dbxupdate.bin (there are three of them) in addition to that of the file contained in latest update to dbx, four in total. I downloaded all dbxupdate.bins releases from UEFI forum’s site and placed them in the UEFI folder. Let us compare the two sets.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

>>> import glob, os, hashlib

>>> files = [ itm for itm in glob.glob(os.path.join(".\\UEFI", "*")) if os.path.isfile(itm) ]

>>> #files names are identical except for a release date (in yyy-mm-dd format) postfix,

>>> #hence sorting by file name means sorting by release date

>>> files.sort()

>>> def get_md5_hash(path):

... with open(path, "br") as f:

... data = f.read()

... return hashlib.md5(data).hexdigest()

...

>>> print(*[ repr(get_md5_hash(f)) for f in files ], sep="\n")

'9275304214f847b261c64e599092c265'

'321878c31426dcf1988a2834c88a291e'

'deb4e1d67664c06925b9c59f2f16934f'

'03ef015d895277b0fd6234f197d28371'

'8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2'

>>> win_hashes = { "9275304214f847b261c64e599092c265",

... "0d157dba3d91f8f5a12b39d68d9b4358",

... "45ac4530ada617e443e343c730a14dfe",

... "8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2" }

>>> win_hashes.intersection({ get_md5_hash(f) for f in files })

{'8d9919cb58914a1f234c682d247a6ee2', '9275304214f847b261c64e599092c265'}

>>> get_md5_hash(".\\UEFI\\dbxupdate_x64_2014-08-11.bin")

'9275304214f847b261c64e599092c265'

The very first Microsoft’s dbxupdate.bin (included in release 1507 of Windows 10) is the same as the first dbxupdate.bin ever published by UEFI forum (in 2014); the latest versions of the file from these two parties are identical as well. On the midmost entries, the (ordered) file sets disagree.

They embarked on the journey together sharing the perfect vision of future to come, cherishing the same heart’s desire to set the world right, then went their separate ways only to meet again on that fateful day, Tuesday, the 9th of August, 2022. While you are looking for a tissue, I will concoct the morale of this touching story: even if things look indistinguishable on the outside, it does not mean they deeply (or even at all) agree on the inside or, in other words, dbxupdate.bin files released by Microsoft and UEFI forum have the same format, but not necessarily the same content.

The next question we will undertake the task of answering is whether Windows dbx updates are “incremental” (in the sense that the content of the update file is appended to what is already in dbx) or not (i.e. the update installer overwrites the dbx value). To this end, we will check if the set of module hashes found dbxupdate.bin is a superset of that stored in dbx.

Obtaining dbx’s value on Linux is as easy as reading from the file /sys/firmware/efi/efivars/dbx-d719b2cb-3d3a-4596-a3bc-dad00e67656f. On Windows, we have a special API call and access rights to grapple with. To save you research effort and implementation time, I wrote a script that would dump to a binary file a value of the NVRAM variable whose name is passed as a parameter.

1

>python win_get_uefi_var.py dbx dbx.esl

dbx.esl being binary, the question arises: how are we to read it? Well, my parser is marked by a certain degree of versatility. Conveniently enough, it can be utilized to parse values of dbx and db variables (in addition to update files).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

>>> from dbxupdate_parser import DbxUpdate, EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST

>>> import construct as cs

>>> upd = DbxUpdate(os.path.expandvars("%windir%\\System32\\SecureBootUpdates\\dbxupdate.bin"), None)

>>> upd_hashes = { s.SignatureData for s in upd.upd.SignatureLists[0].Signatures }

>>> with open("dbx.esl", "rb") as f:

... dbx = f.read()

...

>>> dbx_liststs = cs.GreedyRange(EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST).parse(dbx)

>>> len(dbx_liststs)

1

>>> dbx_hashes = { s.SignatureData for s in dbx_liststs[0].Signatures }

>>> dbx_hashes.issuperset(upd_hashes)

True

>>> dbx_hashes.issubset(upd_hashes)

False

>>> len(dbx_hashes.difference(upd_hashes))

51

On top of all the hashes that arrived packed in the latest update file, dbx includes 51 that did not. Where do they come from? One possibility is that these hashes were preloaded by the manufacturer, in which case they are likely to reside in dbxDefault, a variable that holds a default value of dbx.

1

>python win_get_uefi_var.py dbxDefault dbxDefault.esl

dbxDefault complies with the same format as does dbx, hence the parsing method is the same as well.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

>>> with open("dbxDefault.esl", "rb") as f:

... dbx_def = f.read()

...

>>> print(cs.GreedyRange(EFI_SIGNATURE_LIST).parse(dbx_def))

ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureType = u'{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}' (total 38)

SignatureListSize = 76

SignatureHeaderSize = 0

SignatureSize = 48

SignatureHeader = b'' (total 0)

Signatures = ListContainer:

Container:

SignatureOwner = u'{00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000}' (total 38)

SignatureData = u'0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000' (total 64)

As we see, dbxDefault only holds a dummy all-zeros entry, therefore the 51 extra hashes must have been installed by earlier dbx updates, which clearly indicates incremental nature of the said updates, right? Then how would you explain this?

1

2

3

>>> upd_prev = DbxUpdate(os.path.expandvars("%windir%\\WinSxS\\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1_none_6ab72e7ea4dfef1b\\dbxupdate.bin"), None)

>>> upd_hashes.issuperset(upd_prev_hashes)

True

The previous dbxupdate.bin is entirely contained in the latest one. Perhaps, the nature of updates changed over time.

My suggestion is to go over the entire update history of dbxupdate.bin, examining the consecutive items of the file sequence in a pairwise fashion. Recall that we have learned hashes of four different dbxupdate.bins, each used at some point to set the value of dbx. Of them, two belong to files residing in WinSxS and one – to dbxupdate.bin that, although not present in the system, can be easily downloaded from UEFI forum’s site. There is only one file we do not have a copy of on our list. Here is what its sha256 hash looks like, base64-encoded.

1

2

>>> base64.b64encode(bytes.fromhex("0a15d385e02757ac103e51f52db5e2bdd3c83b60d8337a9c2ae74fbdb303dd9b")).decode()

'ChXTheAnV6wQPlH1LbXivdPIO2DYM3qcKudPvbMD3Zs='

Lovely though the sting is in its own right, I am actually going somewhere with this. I appeal to your memory yet again; do you remember the KB4535680 update, that I found and downloaded only to discover that it generated the version of dbxupdate.bin I already had (if not, skim though the this section)? It transpired, the target file already resided in WinSxS, under the assembly version 10.0.19041.1. What WinSxS did not contain is differentials of any kind, but the update package did: in particular, a reverse differential allowing to reconstruct the preceding version of dbxupdate.bin, which, as its hash will tell you, is exactly the missing file we need.

1

2

3

> python delta_patch.py -i %windir%\WinSxS\amd64_microsoft-windows-s..boot-firmwareupdate_31bf3856ad364e35_10.0.19041.1_none_6ab72e7ea4dfef1b\dbxupdate.bin -d .\KB4535680\u\r\dbxupdate.bin

Applied 1 patch successfully

Final hash: ChXTheAnV6wQPlH1LbXivdPIO2DYM3qcKudPvbMD3Zs=

Now that we have the set of four dbxupdate.bin files in its entirety at our disposal, let us make a rather bold assumption that this is a complete list of dbx update files ever released by Microsoft. With this assumption in mind, we can try and establish set-theoretic (loosely speaking) relations between sets of hashes in consecutive files; to this end, we define a few aux functions (available in the form of a single script for the convenience of those wishing to replicate the experiment).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

def extract_field(sig, field):

"""Recursively extracts either attributes or instance variables (whichever is available) with names from the ``field`` list"""

val = sig

for p in field:

try:

val = getattr(val, p)

except Exception as e:

val = val.__dict__[p]

return val

def get_dbxupdate_entries(files, guid, field):

"""Creates a set of signatures for each file in ``files``

Signature lists with SignatureType != ``guid`` are skipped.

``field`` is a list of instance attributes leading to a value uniquely identifying the signature;

for a X.509 certificate, for example, it might be a serial number:

[EFI_SIGNATURE::SignatureData, X509Cert::_crt, asn1crypto.X509.Certificate::serial_number]

"""

sets = []

for f in files:

upd = DbxUpdate(f , None)

st = set()

for sl in upd.upd.SignatureLists:

if sl.SignatureType != guid:

continue

st = st.union({ extract_field(s, field) for s in sl.Signatures })

sets.append(st)

return sets

def print_set_relations(files, sets):

for i in range(len(sets) - 1):

print(f"intersection: {len(sets[i].intersection(sets[i+1]))}; "\

f"{files[i]}: {len(sets[i])}; "\

f"{files[i + 1]}: {len(sets[i+1])}")

def dbxupdate_matroska(files, guid, field):

"""Prints cardinalities of intersection of signatures found in consecutive files

Accepts sorted list of paths as the parameter ``files``.

If the update files were intended to rewrite existing dbx, each subsequent

set of signatures would be a superset of the previous one, thus forming a

Russian doll of signatures (when no signatures were removed).

"""

sets = get_dbxupdate_entries(files, guid, field)

print_set_relations(files, sets)

For each pair of consecutive update files, we will compute how many hashes they have in common relative to the number of hashes in each file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

>>> import glob, os

>>> files = [ itm for itm in glob.glob(os.path.join(".\\MS", "*")) if os.path.isfile(itm) ]

>>> files.sort()

>>> dbxupdate_matroska(files, "{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}", ["SignatureData"])

intersection: 13; .\MS\dbxupdate_2014.bin: 13; .\MS\dbxupdate_2016.bin: 77

intersection: 27; .\MS\dbxupdate_2016.bin: 77; .\MS\dbxupdate_2019.bin: 33

intersection: 33; .\MS\dbxupdate_2019.bin: 33; .\MS\dbxupdate_2022.bin: 217

>>> dbxupdate_matroska(files, "{a5c059a1-94e4-4aa7-b587-ab155c2bf072}",

... ["SignatureData", "_crt", "serial_number"])

intersection: 0; .\MS\dbxupdate_2014.bin: 0; .\MS\dbxupdate_2016.bin: 0

intersection: 0; .\MS\dbxupdate_2016.bin: 0; .\MS\dbxupdate_2019.bin: 0

intersection: 0; .\MS\dbxupdate_2019.bin: 0; .\MS\dbxupdate_2022.bin: 0

>>> #The (77-27 = 50) hashes that got lost when switching from 2016 to 2019, were never put back into dbxupdate.bin

>>> files = [ ".\\MS\\dbxupdate_2016.bin", ".\\MS\\dbxupdate_2022.bin" ]

>>> dbxupdate_matroska(files, "{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}", ["SignatureData"])

intersection: 27; .\MS\dbxupdate_2016.bin: 77; .\MS\dbxupdate_2022.bin: 217

Updates from Microsoft do not include X.509 certificates at all: module hashes is the only type of signatures one can find there. As for the set inclusion, the test is inconclusive: sometimes the entire set of hashes is carried to the next update, other times only some hashes make it there, while others get removed.

As a last resort, let us merge all the updates together and compare the resulting set of hashes to that held in dbx.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

>>> sets = get_dbxupdate_entries(files, "{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}",

... ["SignatureData"])

>>> from functools import reduce

>>> tot = reduce(lambda a, b: a.union(b), sets, set())

>>> dbx_hashes.issuperset(tot)

True

>>> dbx_hashes.difference(tot)

{'0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000'}

Firstly, I am happy to inform you that we were right in our assumption that we had at our disposal a complete set of the update files.

Despite all the perturbations in the content of update files, in dbx itself, hashes were only added, never deleted or, to put it another way, none of the signatures loaded by an update was removed by the surpassing updates. Evidently, SetVariable() was always called with the EFI VARIABLE APPEND WRITEflag set. Given non-empty intersections, such a procedure is sure to create duplicates thereby resulting in the waste of precious NVRAM space. It turns out not to be the case; here is a quote from UEFI specification:

For variables with the GUID

EFI_IMAGE_SECURITY_DATABASE_GUID(i.e. where the data buffer is formatted asEFI_SIGNATURE_LIST), the driver shall not perform an append ofEFI_SIGNATURE_DATAvalues that are already part of the existing variable value. […] This situation is not considered an error, and shall in itself not cause a status code other thanEFI_SUCCESSto be returned or the timestamp associated with the variable not to be updated.

(That is, UEFI firmware is required to perform a proper union of the signatures being added and those already in dbx.)

NOTE: This small, yet important, note is easy to miss in the vast spaces of UEFI specification; it is Peter Jones’s blog post that brought it to my attention.

On this note, I consider the question of whether the Windows dbx updates are incremental answered. Since we created a “framework” (if this meager set of python functions could be viewed as such) for this type of experiments, why not used it to figure out if the UEFI forum’s updates have the same property?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

>>> files = [ itm for itm in glob.glob(os.path.join(".\\UEFI", "*")) if os.path.isfile(itm) ]

>>> files.sort()

>>> dbxupdate_matroska(files, "{a5c059a1-94e4-4aa7-b587-ab155c2bf072}",

... ["SignatureData", "_crt", "serial_number"])

intersection: 0; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2014-08-11.bin: 0; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-07-29.bin: 2

intersection: 2; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-07-29.bin: 2; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-10-12.bin: 3

intersection: 0; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-10-12.bin: 3; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2021-04-29.bin: 0

intersection: 0; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2021-04-29.bin: 0; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2022-08-12.bin: 0

>>> dbxupdate_matroska(files, "{c1c41626-504c-4092-a9ac-41f936934328}", ["SignatureData"])

intersection: 11; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2014-08-11.bin: 13; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-07-29.bin: 184

intersection: 183; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-07-29.bin: 184; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-10-12.bin: 183

intersection: 180; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2020-10-12.bin: 183; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2021-04-29.bin: 211

intersection: 211; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2021-04-29.bin: 211; .\UEFI\dbxupdate_x64_2022-08-12.bin: 217

Right off the bat, we notice the similarity: a newly released update file often contains a proper subset of the hashes found in the previous one, i.e. some hashes are added, other – removed. A similar pattern is observed in the way X.509 certificates (unlike in Windows, UEFI forum’s updates unitize signatures of type EFI_CERT_X509_GUID) are handled: two certificates appear in the dbxupdate.bin (dated 2020-07-29), the update released on October, 12th adds one more certificate to the set, and finally, on the 29th of April, 2021 all three mysteriously disappear. For the latter, at least, we have an explanation for this update comes with release notes. Here is an extract taken therefrom.

– Added 31 vulnerable shim versions signed by Microsoft UEFI CA 2011.

– Replaced Cisco, Debian and Canonical subordinate CAs with shim hashes to save memory.

– Removed shim not leveraging GRUB and therefore not vulnerable.

Apparently, the certificates in question had been used to sign vulnerable modules (shims, in particular) and in the new update file, they were replaced by the hashes of said modules. Furthermore, 211-180 = 31 new hashes were added and 183-180 = 3 hashed were removed as belonging to the modules not longer deemed vulnerable. This update, it seems, is meant to undo some of the changes made by the one preceding it and, therefore, calling SetVariable() with EFI_VARIABLE_APPEND_WRITE set will not achieve the desired effect. How the update was actually performed by the operating systems that chose to apply dbxupdate.bin from the Forum, I leave to the reader to figure out for, you see, a truly valuable work leaves some problems open, thereby providing the research community with something to pursue :-).

Conclusion

Of course, setting out on a mission to prove that it was a particular update that loaded some hash value into an NVRAM variable is rather silly and the result, in itself, is not worth the time and effort we put in. The real purpose behind the undertaking was to broaden our knowledge. One tiny problem, solved trivially by upgrading Ubuntu LiveCD, comes our way and look how much we have learned! We have learned about OS security objectives and the role Secure Boot plays in achieving them, gotten familiar with specifics of Secure Boot operation and the associated PKI. Now we know about the new type of Windows updates involving differential compression and have an idea (albeit a bit vague) of what is inside the update packages. We dissected the binary format Secure Boot-related variables (and the files that hold patches for them) comply with and have learned how to parse it uncovering a few quaint design decisions along the way.

It was a study beneficial in every way (the effect it had on my meeting deadlines notwithstanding, but hey, if you are procrastinating, at least do it the right way). Thank you for staying till the end.

– Ry Auscitte

References

- Ry Auscitte, A Tale of Omnipotence or How a Windows Update Broke Ubuntu Live CD (2022), Notes of an Innocent Bystander (with a Chainsaw in Hand)

- Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) Specification, Release 2.10 (Aug 29, 2022), UEFI Forum

- Cabinet (file format), Wikipedia

- Jaime Geiger, Extracting and Diffing Windows Patches in 2020

- NTFS reparse point, Wikipedia

- Eric Biggers, ntfs-3g-system-compression: NTFS-3G plugin for reading “system compressed” files

- Joachim Metz, libvshadow: Library and tools to access the Volume Shadow Snapshot (VSS) format

- Windows Updates using forward and reverse differentials, Microsoft Docs

- Peter Jones, The UEFI Security Databases, The Uncoöperative Organization Blog

- B. Kaliski, PKCS #7: Cryptographic Message Syntax Version 1.5, Request for Comments 2315

- Peter Jones, dbxtool: Tool for UEFI Secure Boot DBX updates

- Michael Maltsev, Winbindex: The Windows Binaries Index

- Ry Auscitte, Using WinSxS to Retrace Windows Update History (2023), Notes of an Innocent Bystander (with a Chainsaw in Hand)