First-Stage Bootloader: Hey, You've Got Pointy Ears Sticking out of Your Window

Introduction

The subject of this study came up while I was working on another, more arduous, project. This one seemed a piece of cake by comparison. “I will take a couple-hours break to indulge my curiosity and be back at it in no time,” I thought. Well, my expectations could not have been farther from reality. Hereby the reader is invited to join me in retracing the steps taken as part of this “impromptu” undertaking.

NOTE: If you found your way here by reading this post, you are already familiar with Secure Boot internals. If not, there are plenty of online articles to choose from; so many, in fact, that I found it impossible to sort out my recommendations (the reader is, thus, left with the tough option of deciding for themselves). At the very least, superficial familiarity with the subject is assumed.

According to the UEFI specification, the OS bootloader must be signed with a certificate that either itself is kept in the UEFI variable called db or resides on a chain of trust rooted in some certificate stored there. Nowadays, Windows-certified hardware dominates the market, therefore it is with Microsoft Corporation UEFI CA 2011 (46:de:f6:3b:5c:e6:1c:f8:ba:0d:e2:e6:63:9c:10:19:d0:ed:14:f3) that OS manufacturers sign their bootloaders (typically).

GNU GRUB2 (GRand Unified Bootloader) is the bootloader most commonly used in Linux distributions and one would expect it to come with a neat Microsoft’s signature attached. Surprisingly, it is not the case. Take a look at the signature on grub from Ubuntu Live CD 20.04.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ sbverify --list ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/grubx64.efi

signature 1

image signature issuers:

- /C=GB/ST=Isle of Man/L=Douglas/O=Canonical Ltd./CN=Canonical Ltd. Master Certificate Authority

image signature certificates:

- subject: /C=GB/ST=Isle of Man/O=Canonical Ltd./OU=Secure Boot/CN=Canonical Ltd. Secure Boot Signing

issuer: /C=GB/ST=Isle of Man/L=Douglas/O=Canonical Ltd./CN=Canonical Ltd. Master Certificate Authority

It turns out, signing GRUB2 is against Microsoft’s policy: “Code submitted for UEFI signing must not be subject to GPLv3” (which GRUB2 is). A workaround comes in the form of a shim, a small program that, while itself is signed by Microsoft, holds a copy of whatever certificate GRUB2 is signed with (in the case of Ubuntu, the one from Canonical) and takes on the responsibility of verifying the bootloader before transferring control to it.

This post aims to assert that this verification process is done the way described above. Provided the reader deems it worth following along, we will use instances of shim (BOOTx64.EFI) and grub (grubx64.efi) from Ubuntu’s Ubuntu Live CD v. 20.04 compiled for x64 architecture for the purpose. Methodologically, a hybrid form of static analysis will be employed: binary analysis (for the added benefit of honing our reversing skills) augmented by the same of the source code (Ubuntu being an open source OS, it would be nonsensical not to reap the benefits).

On a final note, crucial to understanding (and, hopefully, appreciating) the narrative is the fact that it comes from the perspective of a person who has no experience in developing UEFI applications.

Without further ado, let us begin.

The First Look and a Quick Fix

The first order of business is to somehow identify the source code the shim image in question was build from. How are we to accomplish the task? Well, it is always a good idea to begin static analysis of a binary with examination of the strings stored inside. Doing so may give us a hint, and, in this case, it, indeed, does:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

$ hexdump -s 0xbfa00 -C -n 0x100 ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI

000bfa00 55 45 46 49 20 53 48 49 4d 0a 24 56 65 72 73 69 |UEFI SHIM.$Versi|

000bfa10 6f 6e 3a 20 31 35 20 24 0a 24 42 75 69 6c 64 4d |on: 15 $.$BuildM|

000bfa20 61 63 68 69 6e 65 3a 20 4c 69 6e 75 78 20 78 38 |achine: Linux x8|

000bfa30 36 5f 36 34 20 78 38 36 5f 36 34 20 78 38 36 5f |6_64 x86_64 x86_|

000bfa40 36 34 20 47 4e 55 2f 4c 69 6e 75 78 20 24 0a 24 |64 GNU/Linux $.$|

000bfa50 43 6f 6d 6d 69 74 3a 20 33 62 65 62 39 37 31 62 |·Commit: 3beb971b·|

000bfa60 31 30 36 35 39 63 66 37 38 31 34 34 64 64 63 35 |·10659cf78144ddc5·|

000bfa70 65 65 65 61 38 33 35 30 31 33 38 34 34 34 30 63 |·eeea83501384440c·|

000bfa80 20 24 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | $..............|

000bfa90 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

000bfb00

The commit number specified by a string stored in the binary, not at all coincidentally, can be found among commits of UEFI Shim Loader on github and this is the source code we are going to use. Locating a version of shim labeled by the exact Ubuntu build on Launchpad is a viable alternative to this approach; what we already have, however, is good enough.

A cursory examination of the source code will produce the following execution path:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

efi_main()

⤷ shim_init()

⤷ set_second_stage()

⤷ init_grub()

⤷ start_image(second_stage)

⤷ load_image()

⤷ handle_image()

⤷ verify_buffer()

⤷ entry_point = ImageAddress(EntryPoint)

⤷ (*entry_point)()

Let us peek inside some of these functions to get a more detailed picture. The code excerpt below, on account of its triviality, should require no explanation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

EFI_STATUS set_second_stage (EFI_HANDLE image_handle)

{

/* [...] */

/* https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L2148 */

second_stage = DEFAULT_LOADER;

/* the path to a second-stage bootloader can sometimes be found in the shim's load options, */

/* but, in case of LiveCD, the default value is used */

/* [...] */

}

//https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.h#L35

#ifdef __x86_64__

#ifndef DEFAULT_LOADER

#define DEFAULT_LOADER L"\\grubx64.efi"

#endif

As this listing demonstrates, it is actually grubx64.efi that the shim loads; next we will see if and how it verifies the module. The relevant snippets of code are collected in the block below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

static EFI_STATUS handle_image (void *data, unsigned int datasize,

EFI_LOADED_IMAGE *li,

EFI_IMAGE_ENTRY_POINT *entry_point,

EFI_PHYSICAL_ADDRESS *alloc_address,

UINTN *alloc_pages)

{

/* [...] */

/* https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L1289 */

efi_status = generate_hash(data, datasize, &context, sha256hash, sha1hash);

/* [...] */

}

static EFI_STATUS verify_buffer (char *data, int datasize,

PE_COFF_LOADER_IMAGE_CONTEXT *context,

UINT8 *sha256hash, UINT8 *sha1hash)

{

/* [...] */

/* https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L1013 */

cert = ImageAddress (data, size, context->SecDir->VirtualAddress);

/* [...] */

/* https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L1099 */

AuthenticodeVerify(cert->CertData,

cert->Hdr.dwLength - sizeof(cert->Hdr),

vendor_cert, vendor_cert_size,

sha256hash, SHA256_DIGEST_SIZE)

/* [...] */

}

Before trying to understand what is going on here, one might benefit from a bit of research. What format would you expect a UEFI application (of which Ubuntu OS bootloader is a special case) to have? Surprisingly enough, it complies with the PE32+ (Portable Executable) format commonly found in the Windows realm. As such, UEFI binaries are cryptographically signed in accordance with the Authenticode standard. Autheticode prescribes that the file signature be stored in the Security Directory (which also goes by the name of Certificate Table) of the PE image and adhere to the DER-encoded PKCS#7 Signed Data (RFC 2315); certificates are, therefore, of X.509 variety. In addition to the signature format, Authenticode determines how a digest of the binary is computed: which parts are included and which are omitted from the digest (a side-by-side comparison shows that generate_hash() function follows the specification to a T).

Empowered by the newly acquired knowledge, we now have no difficulty in inferring what the code does: PE image digest is computed first; then the variable cert is set to point to an instance of Signed Data residing in Security Directory; finally, AuthenticodeVerify() verifies the signature using a X.509 certificate stored in vendor_cert, that is, it makes sure that the signature, when decrypted, matches the PE32+ file digest computed by generate_hash() and subsequently stored in sha256hash. Only then is control passed to GRUB.

NOTE:

Reading through the UEFI specification, an interesting statement captured my attention: “UEFI uses a subset of the PE32+ image format with a modified header signature. The modification to the signature value in the PE32+ image is done to distinguish UEFI images from normal PE32 executables.” A quick way of identifying PE format by the file’s contents, in my understanding, could be something along the lines of this script. However, I see no difference in file signature between UEFI applications and other Windows executables; what I know for sure the difference to consist in is the value of Subsystem.

>>> hex(pe.DOS_HEADER.e_magic)

'0x5a4d'

>>> pe.NT_HEADERS.Signature.to_bytes(2, "little")

b'PE'

>>> pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.Subsystem

10/*from winnt.h*/

#define IMAGE_SUBSYSTEM_EFI_APPLICATION 10A any rate, a mysterious distinguishing signature may turn up when you least expect it. Be warned ;-)

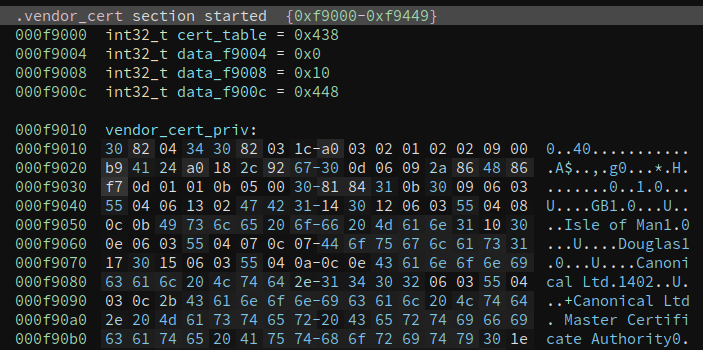

So far so good, but where does vendor_cert come from? The code fragment below reveals the answer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

EFI_STATUS efi_main (EFI_HANDLE passed_image_handle, EFI_SYSTEM_TABLE *passed_systab)

{

/* https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L2573 */

vendor_cert_size = cert_table.vendor_cert_size;

/* [...] */

vendor_cert = (UINT8 *)&cert_table + cert_table.vendor_cert_offset;

/* [...] */

}

// https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L69

extern struct {

UINT32 vendor_cert_size;

UINT32 vendor_dbx_size;

UINT32 vendor_cert_offset;

UINT32 vendor_dbx_offset;

} cert_table;

UINT32 vendor_cert_size;

/* [...] */

UINT8 *vendor_cert;

The structure cert_table is declared as external, so I went ahead and found its definition for you. There you go.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

.globl cert_table

.type cert_table, %object

.size cert_table, 4

.section .vendor_cert, "a", %progbits

cert_table:

#if defined(VENDOR_CERT_FILE) ; defining vendor_cert_size

.long vendor_cert_priv_end - vendor_cert_priv

#else

.long 0

#endif

; [...] omitting vendor_dbx_size definition as irrelevant

.long vendor_cert_priv - cert_table ; defining vendor_cert_offset

; [...] omitting vendor_dbx_offset definition as irrelevant

#if defined(VENDOR_CERT_FILE)

.data

.align 1

.type vendor_cert_priv, %object

.size vendor_cert_priv, vendor_cert_priv_end-vendor_cert_priv

.section .vendor_cert, "a", %progbits

vendor_cert_priv: ; vendor_cert_priv marks the beginning of the certificate

; (it is also used in the computation of vendor_cert_offset)

.incbin VENDOR_CERT_FILE ; including the contents of the binary file VENDOR_CERT_FILE

vendor_cert_priv_end:

; [...]

It takes a bit of focused reading to figure out the assembly definitions, but making the effort will convince the reader that defined here are an instance of the cert_table structure followed by the contents of file VENDOR_CERT_FILE, both placed in a section named .vendor_cert. cert_table::vendor_cert_offset is set so that it holds an offset of the certificate within the section relative to the beginning of cert_table.

By contrast, no effort at all is required to figure out that the environment variable VENDOR_CERT_FILE is initialized with a path to the DER-encoded certificate used to sign GRUB. However, the shim source code we are using is meant to compile all flavours of Linux and, for this reason, comes without a certificate file, the file that would be vendor-specific, i.e. different, for example, for Ubuntu and Fedora. One is supposed to supply the path as an argument to make like shown in the snippet below (if no VENDOR_CERT_FILE is defined, cert_table::vendor_cert_size will be set to zero and signature verification will not take place).

1

make VENDOR_CERT_FILE=our_certificate.cer

In theory, Ubuntu shim should have been linked with the certificate from Canonical, an assumption that is best attested by analyzing the binary. Before going into detail, I thought it a capital idea to establish versions of the python libraries used, so we would be on the same page should someone decide to replicate the experiment. We will utilize the functionality provided by pefile to parse PE files, signify – to verify signatures, and elftools – to work with binaries compiled with GNU toolchain.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Python 3.10.6 (main, Aug 10 2022, 11:40:04) [GCC 11.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import pefile

>>> pefile.__version__

'2022.5.30'

>>> import elftools

>>> elftools.__version__

'0.29'

>>> import signify

>>> signify.__version__

'0.4.0'

With the preliminaries out of the way, it is time to get down to work. The plan is to find the .vendor_cert section, within it – cert_table, and extract the certificate stored at the offset cert_table::vendor_cert_offset. We begin by listing the sections.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

>>> def read_c_string(bt):

... s = ""

... i = 0

... while i < len(bt) and bt[i] != 0:

... s += chr(bt[i])

... i += 1

... return s

...

>>> pe = pefile.PE("./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI")

>>> layout = [ (s.VirtualAddress, s.VirtualAddress + s.SizeOfRawData,

... read_c_string(s.Name)) for s in pe.sections ]

>>> print(*layout, sep="\n")

(20480, 147968, '/4')

(151552, 807424, '.text')

(811008, 811520, '.reloc')

(819200, 819712, '/14')

(823296, 1017856, '.data')

(1019904, 1021440, '/26')

(1024000, 1024512, '.dynamic')

(1028096, 1144832, '.rela')

(1146880, 1209344, '.dynsym')

.vendor_cert is not on the list, which is not a reason to get discouraged for it must be hiding behind one of those cryptic /❮number❭ names. How are we to find it? I suggest taking an easy road. It would not be unreasonable to assume that cert_table is located at the very top of the section, hence the certificate must reside at an offset of sizeof(cert_table) = 4 * sizeof(UINT32). According to Wikipedia, a DER-encoded X.509 certificate should start with the signature 0x3082, so we will look for the .vendor_cert section using this magic number as a marker.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

>>> [ i for i in range(len(pe.sections))\

... if pe.sections[i].get_data()[4 * 4 : 4 * 4 + 2 ] == b'\x30\x82' ]

[5]

>>> print(pe.sections[5])

[IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER]

0x250 0x0 Name: /26

0x258 0x8 Misc: 0x449

0x258 0x8 Misc_PhysicalAddress: 0x449

0x258 0x8 Misc_VirtualSize: 0x449

0x25C 0xC VirtualAddress: 0xF9000

0x260 0x10 SizeOfRawData: 0x600

0x264 0x14 PointerToRawData: 0xEF400

0x268 0x18 PointerToRelocations: 0x0

0x26C 0x1C PointerToLinenumbers: 0x0

0x270 0x20 NumberOfRelocations: 0x0

0x272 0x22 NumberOfLinenumbers: 0x0

0x274 0x24 Characteristics: 0x40100040

Found it! We are almost home free. All that remains to be done is verifying that the certificate GRUB2 is signed with matches the one stored in the .vendor_cert section.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

>>> from signify.authenticode import SignedPEFile

>>> with open("./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/grubx64.efi", "rb") as fl:

... spe = SignedPEFile(fl)

... signed_data = list(spe.signed_datas)[0]

...

>>> from signify.x509 import Certificate

>>> shim_crt = Certificate.from_der(pe.sections[5].get_data()[4 * 4 : ])

>>> grub_crt = signed_data.certificates[0]

>>> grub_crt.sha1_fingerprint

'594ece20591648f5a00de30cf61d118dbece8072'

>>> shim_crt.sha1_fingerprint

'76a092065800bf376901c372cd55a90e1fded2e0'

Alas! The fingerprints are not identical. Perhaps, these certificates chain together, which would suit us just as well.

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> from signify.x509 import CertificateStore, VerificationContext

>>> store = CertificateStore([shim_crt], trusted = True)

>>> ctx = VerificationContext(store)

>>> chain = ctx.verify(grub_crt)

>>> ctx.verify_trust(chain)

True

At this point, I am obliged to inform you that there exists an immediate male descendant of one or both of your grandparents on either paternal or maternal line and his name is Bob. As expected, the certificate stored inside the compiled shim signs the certificate that comes with the GRUB PE file (embedded in PCKS#7 Signed Data), which, in turn, signs the PE file itself. These certificates are assigned the common names “Canonical Ltd. Master Certificate Authority” and “Canonical Ltd. Secure Boot Signing” respectively reflecting the established practice of issuing end-entity certificates for specific purposes while keeping the master key offline as much as possible. It makes revoking certificates easier, too.

I would call it a success. After all, we have successfully demonstrated that Ubuntu shim verifies GRUB2’s cryptographic signature before calling its entry point. Stopping right here might be a prudent thing to do for what follows is a haphazard exercise in reverse engineering that tosses those reckless enough to join in random directions for no good reason. I have the audacity to call it a deep dive into internals of UEFI executables.

The One Where The Trusting Reader Is Led Astray

Do not know about you, my adventurous reader, but the quick-fix-style solution left me with many questions and a nagging feeling of dissatisfaction. Why is it that some sections’ names are slashes followed by numbers (obviously, indices into some table) and others – quite ordinary? What is more, some names suggest that the corresponding sections should not belong in a PE file. Let us try and locate the certificate the right way by adopting a more rigorous approach and, hopefully, unraveling all these mysteries in the process.

It Is All in The Name

Restating the goal, we are looking for an RVA of cert_table structure residing within the .vendor_cert section. As I have already mentioned, examining strings found in the binary is a solid way to begin, especially when one feels clueless as to the best (or any) way of approaching a reverse-engineering problem.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ strings -t x ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI | grep ".vendor_cert"

12fea2 .vendor_cert

1370e6 vendor_cert_priv_end

1370fb vendor_cert_priv

142c27 vendor_cert

142dee vendor_cert_size

$ strings -t x ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI | grep "cert_table"

142ee3 cert_table

So “/26” has a string representation,.vendor_cert, but connection between the two we have yet to figure out. Way more intriguing, however, is the presence of the “cert_table” string; it is a telltale sign that there is a symbol table hidden somewhere in the image. Nowadays, one typically encounters PE binaries built with Microsoft’ toolchain and they come with the symbols stored in separate (pdb) files, not inside the binaries themselves. When one thinks about it, neither does one encounter sections named .dynamic, .dynsym or .rela in PE very often for those are the traits of ELF (Executable and Linkable format) species inhabiting the land of Linux. And once one gets over the associated severe cognitive dissonance, it becomes possible to proceed with the task at hand. Of course, the shim was built using GNU toolchain: gcc and ld, in particular, therefore encountering ELF sections should not strike us as unusual. Besides, skimming though the man pages uncovers ports of ld capable of generating PEs. We will operate under the rather sound assumption that the ELF sections appear as a result of using GNU compilers.

Let us examine “cert_table” in the context, i.e. see what the surrounding bytes of the string look like.

1

2

3

4

5

$ hexdump -s 0x142ed0 -C -n 0x30 ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI

00142ed0 4c 5f 4e 4f 4e 50 49 43 5f 72 65 6c 6f 63 61 74 |L_NONPIC_relocat|

00142ee0 65 64 00 63 65 72 74 5f 74 61 62 6c 65 00 68 6d |ed.cert_table.hm|

00142ef0 61 63 5f 70 6b 65 79 5f 6d 65 74 68 00 74 6c 73 |ac_pkey_meth.tls|

00142f00

At first glance, it seems to be a memory region containing NULL-terminating strings, which is exactly the format .strtab complies with. If we are correct in this assumption, there must also be a matching .symtab section that indexes into its .strtab companion. Ignacio Sanmillan refers to .symtab as “the binary’s global Symbol Table” for it often contains all the symbols referenced in the module; its primary purpose being to aid in debugging, .symtab (along with the corresponding .strtab) is often removed to save space (the resulting binary is said to be stripped).

.symtab is an array of Elf64_Sym structures.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct {

Elf64_Word st_name;

unsigned char st_info;

unsigned char st_other;

Elf64_Half st_shndx;

Elf64_Addr st_value;

Elf64_Xword st_size;

} Elf64_Sym;

The first field is an index into the .strtab section, hence a symbol name is obtained by executing a statement along the lines of

1

char* sym_name = (char*)strtab_ptr + sym->st_name;

It is easy to determine boundaries of the alleged .strtab by visual inspection (keeping in mind that a string table is supposed to begin with a NULL character prepending the first string). I employed hexdump for the task, but will spare you a rather lengthy (0x1436f0 - 0x12fe8b = 79973) dump. Instead, let us take a look at the strings stored inside.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

>>> def split_into_substrings_ex(dynstr):

... l = 0

... lst = []

... while l < len(dynstr):

... s = read_c_string(dynstr[l:])

... if s == "":

... l += 1

... else:

... lst.append((l,s))

... l += len(s)

... return lst

...

>>> strtab = pe.__data__[0x12fe8b : 0x1436f0]

>>> len(split_into_substrings_ex(strtab))

4243

>>> print(*split_into_substrings_ex(strtab)[0:10], sep = "\n")

(1, '.eh_frame')

(11, '.data.ident')

(23, '.vendor_cert')

(36, 'StrCaseCmp')

(47, 'StrnCaseCmp')

(59, 'is_all_nuls')

(71, 'count_ucs2_strings')

(90, 'shim_cert')

(100, 'sk_ASN1_OBJECT_num')

(119, 'sk_ASN1_OBJECT_value')

Well, the region contains quite a few strings, so it may very well be a companion to the global symbol table. That said, the first three entries are section names, which is unusual for .symtab. We will have to get back to it later.

There is another option. The pair .dynsym and .dynstr follows exactly the same format (as does < .symtab, .strtab>); that being the case, .dynstr is what this mysterious string “array” might be. The fact that the binary actually has a .dynsym section is in favor of this hypothesis. However, .dynsym being limited to the symbols that are resolved at runtime by a dynamic linker, is unusually a feature of shared libraries. I see no place for dynamically resolved symbols in this image. Take a look at the data directories it contains.

1

2

>>> [ s.name for s in pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.DATA_DIRECTORY if s.Size > 0 ]

['IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_SECURITY', 'IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_BASERELOC']

The only data directories with non-zero headers are certificate table, where shim’s signature is stored (BOOTx64.EFI is signed with Microsoft’s certificate so that Secure Boot does not turn up its nose at running it), and base relocation table (which is not surprising considering that module’s base address is not set); there are no imports or exports. From PE32+ format perspective, it is a stand-alone executable module. Besides, the shim is to run in a UEFI boot environment where is no Linux loader and dynamic linker available to process .dynsym. Something sneaky is going on here and this is yet another thing we will leave for later consideration.

Now let us try to determine which section (if any) the “cert_table” string belongs to.

1

2

3

>>> scts = [ (s.PointerToRawData, s.PointerToRawData + s.SizeOfRawData) for s in pe.sections ]

>>> [ c for c in scts if c[0] <= 0x142ee3 and c[1] > 0x142ee3 ]

[]

None of them! This is not a reason to get discouraged. On the contrary, a symbol table, when used for debugging only, is not expected to be mapped into RAM at runtime, and, therefore, can lie in intersectional space. Why not identify the boundaries of the byte range that resides between sections and contains the “cert_table” string with a view to unearth more hitherto unaccounted for data?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>> sd = next(filter(lambda x: x.name == "IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_SECURITY",

... pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.DATA_DIRECTORY))

>>> scts.append((sd.VirtualAddress, sd.VirtualAddress + sd.Size))

>>> intr = [ ( scts[i][1], scts[i + 1][0] - scts[i][1] )

... for i in range(len(scts) - 1) if scts[i + 1][0] > scts[i][1] ]

>>> intr

[(1161216, 163568)]

>>> hex(intr[0][0]), hex(intr[0][1] + intr[0][0])

('0x11b800', '0x1436f0')

This code snippet requires some explanation. To begin with, layout of an executable in memory is typically different from that on a hard drive; for one, the loader should respect alignment requirements for the section’s load address, whereas in file the image can be stored more compactly; in this setting, PointerToRawData is a file pointer to the first byte of the section and VirtualAddress is an RVA (relative virtual address) – an offset relative to the address at which the module has been loaded. Then, a directory is usually located within one section or other, but security directory is an exception to this rule: file signature is not needed at runtime, therefore it is not loaded as part of the image. For this reason, security directory’s VirtualAddress, which is normally an RVA, is a file pointer instead. It is also the reason why we have to handle the security directory separately when looking for an unaccounted for regions of data within the file.

So there is an unidentified region (nearly 160Kb in size) in the PE file: [0x11b800, 0x1436f0), the last 78Kb of which ([0x12fe8b : 0x1436f0)) are ostensibly occupied by .strtab. What is the remaining portion for? One would expect .symtab to be there, would one not? Let us peek at the first few bytes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

$ hexdump -s 0x11b800 -C -n 0x80 ./LiveCD/EFI/BOOT/BOOTx64.EFI

0011b800 2e 65 78 69 74 00 00 00 28 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 |.exit...(.......|

0011b810 03 00 64 75 6d 6d 79 00 00 00 72 6f 01 00 05 00 |..dummy...ro....|

0011b820 00 00 03 00 6c 61 62 65 6c 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 |....label1......|

0011b830 03 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 27 00 00 00 29 00 |..........'...).|

0011b840 00 00 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 32 00 00 00 |............2...|

0011b850 fd 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 3e 00 |..............>.|

0011b860 00 00 f2 01 00 00 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

0011b870 4a 00 00 00 3b 02 00 00 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 |J...;...........|

0011b880

Whatever items this region holds, clearly, these are not instances of Elf64_Sym since symbol names are included explicitly rather than referenced. In fact, from my previous experience, it is pdb files that store symbol names within the structure (PUBSYM32) describing the symbols, but the layout is different, with the symbol name being the last field in the structure, whereas here the name comes first. But then, debug information has gone though many incarnations over the years. Perhaps, we are dealing with an earlier version. Let us keep it in mind.

Further examination of the hex dump brought no joy: unable to locate a symbol table and, as a result, concluding I was on the wrong track, I decided to explore other options. As of now, those naively following alone appear to be destined to wander around in vain till the end of time.

Halloween Vibes: Spooky Ghost Sections

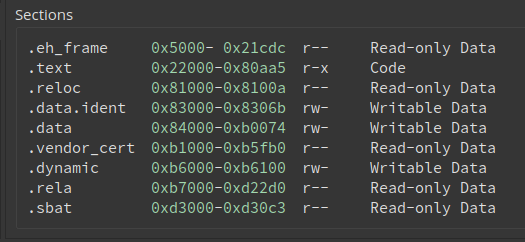

Starting over, let us take another look at the list of sections.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# layout of the binary in memory

>>> layout = [ (s.VirtualAddress, s.VirtualAddress + s.SizeOfRawData,

... read_c_string(s.Name)) for s in pe.sections ]

>>> print(*layout, sep="\n")

(20480, 147968, '/4')

(151552, 807424, '.text')

(811008, 811520, '.reloc')

(819200, 819712, '/14')

(823296, 1017856, '.data')

(1019904, 1021440, '/26')

(1024000, 1024512, '.dynamic')

(1028096, 1144832, '.rela')

(1146880, 1209344, '.dynsym')

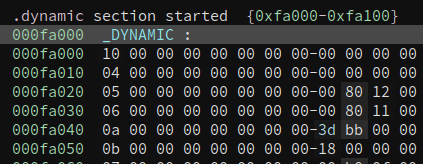

It is yet unclear why, but in the shim PE image, there are sections pertaining to dynamic linking: .dynsym, .dynamic – and not one but two sections with relocation data. The section called .dynamic contains working information for dynamic linker, in particular, all the sections facilitating the dynamic linking procedure are listed there.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

# initiaize tools for parsing ELF files

>>> from elftools.elf.structs import ELFStructs

>>> es = ELFStructs(True, 64) #we will parse little-endian 64-bit ELF structures

>>> es.create_basic_structs()

>>> es.create_advanced_structs()

# loop over .dynamic enties while trying to locate the sections they refer to

>>> offsets = 0

>>> sym = es.Elf_Dyn.parse(pe.sections[6].get_data()[offsets : ])

>>> while sym["d_tag"] != "DT_NULL":

... print(sym, [ s[2] for s in layout if sym['d_ptr'] >= s[0] and sym['d_ptr'] < s[1] ])

... offsets += es.Elf_Dyn.sizeof()

... sym = es.Elf_Dyn.parse(pe.sections[6].get_data()[offsets : ])

...

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_SYMBOLIC', 'd_val': 0, 'd_ptr': 0}) []

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_HASH', 'd_val': 0, 'd_ptr': 0}) []

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_STRTAB', 'd_val': 1212416, 'd_ptr': 1212416}) []

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_SYMTAB', 'd_val': 1146880, 'd_ptr': 1146880}) ['.dynsym']

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_STRSZ', 'd_val': 47933, 'd_ptr': 47933})<<redacted>>

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_SYMENT', 'd_val': 24, 'd_ptr': 24}) []

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_RELA', 'd_val': 1028096, 'd_ptr': 1028096}) ['.rela']

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_RELASZ', 'd_val': 116424, 'd_ptr': 116424})<<redacted>>

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_RELAENT', 'd_val': 24, 'd_ptr': 24}) []

Container({'d_tag': 'DT_FLAGS', 'd_val': 2, 'd_ptr': 2}) []

A little sanity check before we continue:DT_SYMENT tells us the size of DT_SYMTAB’s entries.

1

2

>>> es.Elf_Sym.sizeof()

24

Well, a symbol table resides in the .dynsym section, as it should. Also, .dynamic holds a promise of a string table to accompany it, i.e. the string table is supposed to be loaded at the address d_ptr = 1212416 = 0x128000, but there is no section to accommodate it! In an attempt to dig up the missing section, let us examine the flags of the last section in the PE-file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

>>> pe.print_info()

[...]

[IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER]

0x2C8 0x0 Name: .dynsym

0x2D0 0x8 Misc: 0xF2E8

0x2D0 0x8 Misc_PhysicalAddress: 0xF2E8

0x2D0 0x8 Misc_VirtualSize: 0xF2E8

0x2D4 0xC VirtualAddress: 0x118000

0x2D8 0x10 SizeOfRawData: 0xF400

0x2DC 0x14 PointerToRawData: 0x10C400

0x2E0 0x18 PointerToRelocations: 0x0

0x2E4 0x1C PointerToLinenumbers: 0x0

0x2E8 0x20 NumberOfRelocations: 0x0

0x2EA 0x22 NumberOfLinenumbers: 0x0

0x2EC 0x24 Characteristics: 0x40400040

Flags: IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_16BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_2048BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_32BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_4096BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_64BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_8192BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_8BYTES, IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_MASK, IMAGE_SCN_CNT_INITIALIZED_DATA, IMAGE_SCN_MEM_READ

[...]

Notice the flag IMAGE_SCN_ALIGN_8192BYTES is set, which means that the first byte of the section should reside on an 8Kb boundary. It stands to reason that the next section, if it had existed, would have been complied with the same alignment requirements, therefore it would have been placed at the address:

1

2

>>> (layout[8][1] // 8192 + 1) * 8192

1212416

It is the same address, according to the data in .dynamic, where the sting table is supposed to be. Not only do we know the address of this ghost section, but we also know its size: 47933 bytes, as the entry tagged DT_STRSZ indicates. The string table must contain exactly the number of strings referenced in the symbol table and, in all probability, it does, that is to say, it would have (had it existed).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>> sidx = [ i for i in range(len(pe.sections))

... if pe.sections[i].Name.decode("utf-8").startswith(".dynsym") ][0]

>>> dynsym = pe.__data__[ pe.sections[sidx].PointerToRawData :

... pe.sections[sidx].PointerToRawData +\

... pe.sections[sidx].SizeOfRawData ]

>>> symbols = [ es.Elf_Sym.parse(dynsym[i * es.Elf_Sym.sizeof() : ])

... for i in range(len(dynsym) // es.Elf_Sym.sizeof()) ]

>>> max([ s.st_name for s in symbols ])

47922

(keep in mind that s.st_name is a zero-based index, and, as such, should be less than the table size by at least one)

The alleged .strtab wont’s fit the bill: the size does not match, neither do the offsets. Take a look.

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> len(strtab)

79973

#st_names point somewhere "mid-string", not the first chars in symbol names

>>> [ read_c_string(strtab[s.st_name : ]) for s in symbols ][0:10]

['', '_errors', 'KCS7_ATTR_SIGN_item_tt', 'base', 'gnctx', 'alid_star', 'err_string_data_hash', 'ch_ex_', 'N_push', 'me']

As a result, we reach the conclusion that .dynsym does not have a matching symbol table; it was supposed to occupy a ghost section, immediately following the last section of PE file, but, for some reason, had been cut off. Another weird thing about the symbols in .dynsym is that the indices of the sections they belong to are all over the place.

1

2

>>> set([ s.st_shndx for s in symbols ])

{1, 3, 'SHN_ABS', 6, 7, 8, 10, 'SHN_UNDEF'}

There are 9 sections only in the PE file, most of them performing auxiliary functions and, thus, not holding any code or program data (i.e. not holding any sources of symbols). What is more, Binary Ninja cannot find any references to the .dynsym section in the code. Apparently, .dynsym is yet another spooky ghost section, that might have had some purpose in the original object file before something terrible happened to it (as I am writing the draft at the very end of October, these references to the otherworld appear quite fitting).

What else is there? .dynamic also contains a DT_RELA entry signifying the fact that there is a relocation table in the section named .rela. “If this element is present,” the documentation claims, “the dynamic structure must also have DT_RELASZ and DT_RELAENT elements.” Indeed, relocation tables come in a variety of formats, with DT_RELAENT determining which one the table adheres to by specifying the size of its entries. Let us see…

1

2

3

4

5

>>> es.Elf_Rela.sizeof()

24

>>> rela = pe.sections[7].get_data()

>>> len(rela)

116736

Out of all relevant structures, Elf64_Rela only meets the size requirement. So Elf64_Rela it is! As to the length, it is a little bit off. It turns out, the table is padded with zeros, which explains the difference perfectly. Aware of this fact, we will use the r.r_info_type > 0 condition to exclude the invalid all-zero elements.

1

2

3

4

5

6

//https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E19683-01/816-1386/chapter6-54839/index.html

typedef struct {

Elf64_Addr r_offset;

Elf64_Xword r_info; /*symbol index and type*/

Elf64_Sxword r_addend;

} Elf64_Rela;

As we will see shortly, the relocation table may actually contain valid data: at least, all the relocations are of the same type, R_386_RELATIVE = 8 (i.e. base relocation), and point within the .data section, none of it being in the slightest unreasonable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

>>> rels = [ es.Elf_Rela.parse(rela[i * es.Elf_Rela.sizeof() : ])

... for i in range(len(rela) // es.Elf_Rela.sizeof()) ]

>>> set([r.r_info_type for r in rels if r.r_info_type > 0])

{8}

>>> set([ ([ l[2] for l in layout if l[0] <= r.r_offset and l[1] > r.r_offset ] + ["?"])[0]

... for r in rels if r.r_info_type > 0])

{'.data'}

For a stand-alone PE file, having a relocation table is not as unusual as it may seem: even though the shim has no imports, it can still be loaded at a random address in memory. What is more, in our case, base relocation section is even necessary: when it is absent and the flag IMAGE_FILE_RELOCS_STRIPPED (in IMAGE_FILE_HEADER::Characteristics) is set, Windows loader either loads the module at its preferred base address or fails, returning an error. Well, this PE file specifies no valid preferred base address.

1

2

>>> pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase

0

However, in the shim, the PE base relocation section is fake; moreover, it is different from the .rela section referenced by .dynamic. Let me explain.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

>>> [ ( hex(s[0]), hex(s[1] - s[0]), s[2] ) for s in layout if s[2].startswith(".rel") ]

[('0xc6000', '0x200', '.reloc'), ('0xfb000', '0x1c800', '.rela')]

>>> pe.print_info()

[...]

[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_BASERELOC]

0x130 0x0 VirtualAddress: 0xC6000

0x134 0x4 Size: 0xA

----------Base relocations----------

[IMAGE_BASE_RELOCATION]

0xBF800 0x0 VirtualAddress: 0x19F72

0xBF804 0x4 SizeOfBlock: 0xA

[...]

The native PE base relocation table is located in the .reloc section and it is only 10 bytes in length. Here is its contents.

1

2

3

000bf800 72 9f 01 00 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |r...............|

000bf810 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

Following the documentation, it is easy to dissect the section data into the fields of a relocation block.

72 9f 01 00(4 bytes) – page RVA0a 00 00 00(4 bytes) – size of entire block (including the page RVA and itself), i.e. 0xA = 4 + 4 + 20(4 bits) – type0 00(12 bits) – offset

The block holds one entry only and its type is IMAGE_REL_BASED_ABSOLUTE (0), which corresponds to: “The base relocation is skipped. This type can be used to pad a block.”

The relocation table contains no useful data! It is a dummy, and, going a few paces forward, it has been intentionally created this way.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

¡// https://github.com/rhboot/gnu-efi/blob/03670e14f263ad571bf0f39dffa9b8d23535f4d3/gnuefi/crt0-efi-x86_64.S#L64¡

¡// hand-craft a dummy .reloc section so EFI knows it's a relocatable executable:¡

.data

.dummy0:

.dummy1:

.long 0

#define IMAGE_REL_ABSOLUTE 0

.section .reloc, "a"

.long .dummy1-.dummy0 ¡// Page RVA¡

.long 10 ¡// Block Size (2*4+2)¡

.word (IMAGE_REL_ABSOLUTE<<12) + 0 ¡// reloc for dummy¡

It turns out, the task of relocation in its entirety rests on the shoulders of linux-style .rela. However, since the shim is launched in the UEFI boot environment, there is no ELF loader to perform the procedure, hence the only remaining candidate for the job is the executable itself. It puts me in mind of MSVCRT that provides a wrapper around the main() function in order to initialize the C++ runtime, which, in turn, makes me wonder about what is happening at the entry point of BOOTx64.dll. I am enlisting the help of Binary Ninja Version 3.1.3470 to assist me in this endeavor.

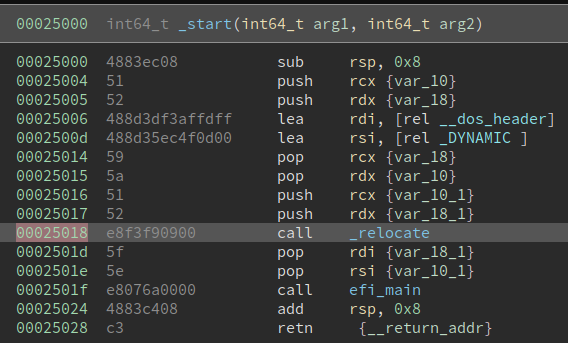

1

2

3

4

>>> hex(pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.AddressOfEntryPoint)

'0x25000'

>>> (hex(layout[6][0]), hex(layout[6][1]), layout[6][2])

('0xfa000', '0xfa200', '.dynamic')

So what do we see here? I do not know about you, my reader, but what captures my attention is the complete absence of difficulty in extracting the symbols (including their names) on Binary Ninja’s part, which puts my own skills to shame. But also, we notice that _start(), having loaded an address of the .dynamic section into rsi (recall that System V ABI passes its arguments in rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, r9), calls _relocate(). Thus, we discover .dynamic’s raison d’être: it tells the _relocate() subroutine where the relocation table is!

Now that we figured out that at least the relocation table has a purpose, we recall that its entries have a field (embedded into Elf64_Rela’s bitfield r_info) that indexes into .dynsym (for those entries where the relocation address has a corresponding symbol). Maybe, .dynsym is not a ghost section after all.

1

2

>>> set([ r.r_info_sym for r in rels ])

{0}

Nope, that was not it.

On Benefits of Admitting Defeat

Let us be honest, nobody reads instructions. We grapple with the nuisance by a very scientific method of taking random actions (otherwise known as trial and error) in hopes that, given enough attempts is made, a chance will point us in the right direction till we develop aim of a pitcher and there is nothing left at our disposal but a kitchen sink. Then comes the time to admit our defeat and, with bitterness in our hearts, reach for the documentation. Related in the previous sections is how far I have gotten before it was time…

A built-in relocation routine, the most peculiar occurrence by all accounts, reminded me of other libraries replacing the entry point with their initialization procedures, C runtime being the most common example, so to the list of imported libraries I turned my attention. A quick examination thereof revealed that the functionality of handing UEFI specifics was encapsulated in gnu-efi SDK. The SDK came with an amazingly comprehensive readme file (which I cannot recommend enough); I found it most enlightening, albeit sightly outdated. Here is what I have learned.

The main purpose of gnu-efi is to provide the possibility for building a UEFI application (or a driver) using GNU toolchain, a non-trivial undertaking due to the fact that classic GNU toolchain creates System V ELF images, whereas UEFI expects PE32+ files. The way gnu-efi solves the problem is by building an ordinary statically-linked ELF executable and then transforming it into a PE file, with the transformation affecting structure of the container and not so much the code. Inside, it remains a gcc-compiled linux application (in that it uses System V calling convention, ELF segments, and internal structures such as GOT or PLT), but, as David Rheinsberg points out, a freestanding one, i.e. it, designed to run in a freestanding environment, does not assume availability of standard library, rely on the operating system loader to resolve references, or count on linux syscalls, but either implements the necessary functionality itself or uses UEFI boot services instead. The latter one is also not without its problems. The shim, being executed in the UEFI environment, must comply with its calling convention, which is the same as that of Windows ABI (not System V!). Therefore, gnu-efi provides mediators that put the function arguments in proper registers, perform “shadow space” allocation on stack, save and restore non-volatile registers, and handle other calling convention-related issues.

A typical ELF executable contains code that uses absolute addressing. Why would it not? A Linux application has entire user-mode portion of its address space at its disposal. Of course, in some cases this arrangement may not be possible (for example, when the binary is subject to ASLR), but we will not discuss it here. The gnu-efi readme states: “Since EFI binaries are executed in physical mode, EFI cannot guarantee that a given binary can be loaded at its preferred address.” What the statement implies is architecture-dependent: on Itanium the UEFI applications are, indeed, loaded in physical mode. On x64, on the other hand, the situation is more complicated: in particular, even though a UEFI application is loaded with paging enabled, the memory is identity-mapped, i.e., virtual addresses equal to physical ones. In effect, the application shares its memory with the rest of UEFI in addition to the mapping being limited to valid physical addresses. Naturally, the OS loader will eventually define its own page directory and page tables, but it is the state of the boot environment when the binary is being loaded that interests us.

Since the UEFI application can be loaded at a random base address, it must be relocatable and the kind of ELF that meets this requirement is a shared library (also known as a shared object, *.so). These files contain mostly position-independent code with relative addressing between segments (segments’ relative positions remain the same from run to run); where absolute addressing is necessary, proper values are filled in by the process of relocation (which is usually done via Global Offset Table, GOT). Apart from relocation, loading a shared library usually involves symbol resolution: replacing stubs with the actual addresses of the symbols referenced by their names from outside the library – a task accomplished with the help of symbol tables. The sections .dynamic, .rela, .dynsym, and .dynstr constitute the framework allowing to load a shared object, so, shim being set to compile as a shared library, it is not surprising that we came across them.

What sets shim apart is that its makefile is designed to produce a fully-resolved shared object. As such, the shim does not need symbol resolution and uses only a limited subset of possible relocations. The gnu-efi readme states that, for x86 architectures, R_386_RELATIVE is the only required type; I assume, this statement to be correct for x86-64 as well, since, if the reader remembers, this is the only type of relocations we found in the shim’s .rela section. In essence, R_386_RELATIVE is the same as base relocation: it adds the base address to r_addend and records the result at r_offset.

When .dynsym, comes into play is compiling the shim for Intel Itanium architectures, where function address is not sufficient and it is necessary to construct a function descriptor, which, in turn, requires access to a symbol table. It is all well and good, but why would a x64 binary contain .dynsym? The answer is: I do not know. However, here an excerpt from the the shim’s makefile; in it, .dynsym is passed as an argument to objcopy, a utility that transforms ELF shared libraries into PE executables.

1

2

3

4

5

6

¡#https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/Makefile#L192¡

$(OBJCOPY) -j .text -j .sdata -j .data -j .data.ident \

-j .dynamic -j ·.dynsym· -j .rel* \

-j .rela* -j .reloc -j .eh_frame \

-j .vendor_cert \

$(FORMAT) $^ $@

Perhaps, .dynsym is an artifact that found its way into the list of sections for historic reasons. At any rate, in a newer shim image, that for Ubuntu 22.04, it is no longer there.

Normally, it is Linux’s dynamic loader who handles the relocations, but, while an operating system is booting, there is nobody to take on the responsibility for “rebasing” the module, so, with gnu-efi, this functionality is integrated into the binary itself, as we could observe earlier (recall the _relocate() function). All the developer has to do is to specify the entry point like so: ENTRY(_start).

Wrapping up the section, let me remind you that we have found .rela to reference addresses in .data only. This is what the documentation says about shared objects:

Position-independent code cannot, in general, contain absolute virtual addresses. Global offset tables hold absolute addresses in private data, thus making the addresses available without compromising the position-independence and shareability of a program’s text. A program references its global offset table using position-independent addressing and extracts absolute values, thus redirecting position-independent references to absolute locations. […] Much as the global offset table redirects position-independent address calculations to absolute locations, the procedure linkage table (PLT) redirects position-independent function calls to absolute locations.

Could not have said it better myself ;-) Anyways, one would expect GOT and PLT contents to be the major targets of the relocation procedure, which does not seem to agree with the observation we made earlier. In order to understand what is happening, check out the definition of .data section in the linker script file supplied to ld.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

¡/* https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/elf_x86_64_efi.lds#L38 */¡

.data :

{

_data = .;

*(.rodata*)

·*(.got.plt)·

·*(.got)·

[...]

}

.data contains both, GOT and PLT, hence the fact that relocations update .data section only is not at all surprising.

And One More Thing

Somehow I find myself unable to leave the poor .dynsym alone. But this is the last attempt, I promise.

Since the .dynsym section is there (or once was there), its entries are intended to help in either symbol resolution or relocation. Symbol resolution off the table, let us at least try our luck with relocation: for example, let us check if there is an entry for .cert_table in .dynsym. Having learned (by applying a quick-and-dirty approach) that cert_table is located at the very beginning of section /26, we already know how st_value should be initialized. Someone would call it cheating, I call it optimization!

1

2

>>> [ s for s in symbols if s.st_value == pe.sections[5].VirtualAddress ]

[Container({'st_name': 1609, 'st_info': Container({'bind': 'STB_GLOBAL', 'type': 'STT_OBJECT'}), 'st_other': Container({'local': 0, 'visibility': 'STV_DEFAULT'}), 'st_shndx': 8, 'st_value': 1019904, 'st_size': 4})]

With the string table missing, it is impossible to verify if the name offset is valid. Likewise, size of the object referenced by the symbol and the section index, both, look suspicious: there is .rela section at index 8 (in the Elf64_Sym structure, the section indices are 1-based), a section that should not be referenced by symbols at all. Perhaps, the index pertains to the section order in the original .so file, not the resulting PE, in which case, ‘st_value` is not the field to rely on when identifying a symbol for the PE will have a different layout and RVAs won’t match. There is nothing we can do about it.

Let us at least check if .cert_table is subject to relocation (taking into account that the preferred base address is set to zero).

1

2

>>> [ r for r in rels if r.r_addend == pe.sections[5].VirtualAddress ]

[]

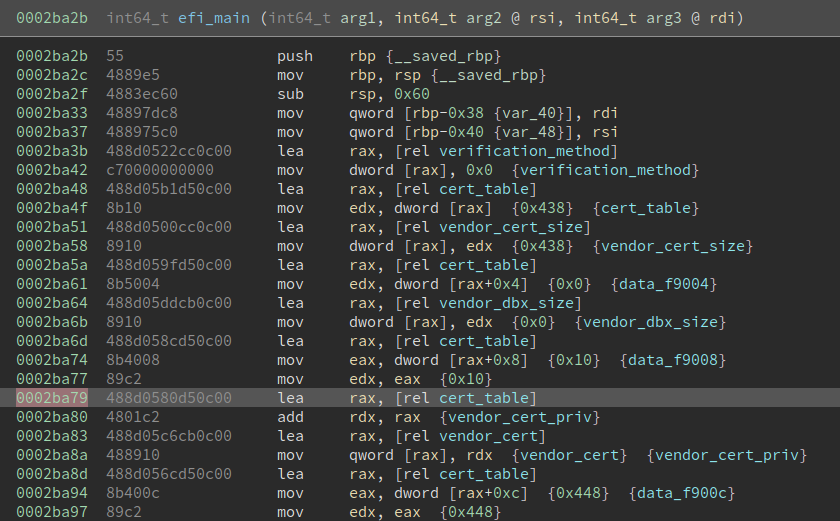

No luck here either. But it gives rise to an interesting experiment. If the structure is not relocated, it must be accessed by position-independent instructions only. In order to confirm it, we turn to Binary Ninja to disassemble the portion of machine code where .cert_table is read. Familiarizing ourselves with the source code first will make the task easier.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

EFI_STATUS efi_main (EFI_HANDLE passed_image_handle, EFI_SYSTEM_TABLE *passed_systab)

{

// https://github.com/rhboot/shim/blob/3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c/shim.c#L2573

vendor_cert_size = cert_table.vendor_cert_size;

// [...]

vendor_cert = (UINT8 *)&cert_table + cert_table.vendor_cert_offset;

// [...]

}

Now to the disassembler!

What do we see here? That is right! More of those nefarious variable names that, no doubt, have been placed there specifically to tease me about my proficiency in locating symbol tables (or the lack thereof, to be precise). Also, there are quite a few instructions lea rax, rel cert_table in the listing; they record a relative offset of cert_table in rax, but relative to what? Well, an observant reader will have noticed that all these instructions have different machine codes, so it stands to reason that the addressing is relative to the value of instruction pointer (or a program counter if you so please). I went ahead and disassembled the instruction selected on the screeenshot (I am using https://defuse.ca/ for the purpose).

1

48 8d 05 80 d5 0c 00 lea rax,[rip+0xcd580] # 0xcd587

Et voilà! The addressing is, indeed, relative to rip; however, keep in mind: it is not the address of the instruction currently executed that is taken as the rip value, but that of the instruction immediately following it. During the static analysis rip is obviously not known – the best we can do is use an RVA in its stead: 0xcd587, thereby getting 0xf9000 = 0x2ba80 + 0xcd580. And there you have it: cert_table is read from the RVA 0xf9000.

Position-independent addressing is used to access cert_table; not relocation is needed.

The Mystery of Elusive Symbol Table Solved

So what is this “secret” symbol table that everyone (but me) seems to know about?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

>>> layout = [ (s.VirtualAddress, s.VirtualAddress + s.SizeOfRawData,

... read_c_string(s.Name)) for s in pe.sections ]

>>> print(*layout, sep="\n")

(20480, 147968, '/4')

(151552, 807424, '.text')

(811008, 811520, '.reloc')

(819200, 819712, '/14')

(823296, 1017856, '.data')

(1019904, 1021440, '/26')

(1024000, 1024512, '.dynamic')

(1028096, 1144832, '.rela')

(1146880, 1209344, '.dynsym')

Taking a closer look at the list of PE sections, three of them clearly stand out: /4, /14, /26. Conveniently, the NULL-terminated-strings-filled region of memory, that turned out not to be an ELF string table, contains exactly three strings looking suspiciously like section names.

1

2

3

4

>>> print(*split_into_substrings_ex(strtab)[0:3], sep = "\n")

(1, '.eh_frame')

(11, '.data.ident')

(23, '.vendor_cert')

The numbers prefixed by forward slashes may very well be offsets into whatever this region is, but the values are a little off. Let us shift the region boundary by a few bytes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> strtab = pe.__data__[ 0x12fe88 : (intr[0][0] + intr[0][1]) ]

>>> print(*split_into_substrings_ex(strtab)[0:4], sep = "\n")

(0, 'f8\x01')

(4, '.eh_frame')

(14, '.data.ident')

(26, '.vendor_cert')

Now the numbers match perfectly! However, the first four bytes of the updated region no longer contain symbolic data. Perhaps, they encode auxiliary information such as region length, which is a sensible enough guess for structures of varying length are often length-prefixed.

1

2

3

4

>>> int.from_bytes(strtab[0:4], "little")

79974

>>> len(strtab)

79976

The two-byte difference is easily explainable by the fact that the region is zero-padded.

1

2

3

>>> ln = len(strtab)

>>> ( strtab[ln - 1], strtab[ln - 2], strtab[ln - 3], strtab[ln - 4] )

(0, 0, 0, 116)

As you see, there are two extra zeros at the end.

So far so good, but the question remains why some section names are placed in the PE headers “as is” and other – encoded in this manner. Of many possible answers to this question, Occam Razor leaves us with one only: there must be a limit on the name length. A quick glance at the documentation confirms that this guess is correct.

An 8-byte, null-padded UTF-8 encoded string. […] For longer names, this field contains a slash (/) that is followed by an ASCII representation of a decimal number that is an offset into the string table. Executable images do not use a string table and do not support section names longer than 8 characters. Long names in object files are truncated if they are emitted to an executable file.

Apparently, long section names are a feature of object files, not fully-linked images. An attempt to find a proper way of locating the string table mentioned in the documentation (certainly, we were not meant to browse the “unused” space between PE sections) led me to a header referencing both, the string table and a symbol table.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

>>> pe.print_info()

[...]

[IMAGE_FILE_HEADER]

0x84 0x0 Machine: 0x8664

0x86 0x2 NumberOfSections: 0x9

0x88 0x4 TimeDateStamp: 0x0 [Thu Jan 1 00:00:00 1970 UTC]

0x8C 0x8 PointerToSymbolTable: 0x11B800

0x90 0xC NumberOfSymbols: 0x1224

0x94 0x10 SizeOfOptionalHeader: 0xF0

0x96 0x12 Characteristics: 0x206

Flags: IMAGE_FILE_DEBUG_STRIPPED, IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE, IMAGE_FILE_LINE_NUMS_STRIPPED

[...]

>>> hex(intr[0][0]), hex(intr[0][1] + intr[0][0])

('0x11b800', '0x1436f0')

My thoughtful reader will surely remember the data region we encountered earlier, that of unidentified purpose residing in an intersectional space of the shim PE file. Now we know what it is – a COFF symbol table followed by the associated string table. The latter is stored at the offset computed by the formula PointerToSymbolTable + NumberOfSymbols * sizeof(<structure describing a symbol>).

However, the documentation insists on PointerToSymbolTable being set to zero for executable images and kindly but firmly reminds us that COFF debug information format (of which this symbol table is a part) is deprecated. For more information on the subject, I suggest reading Oleg Starodumov’s article; basically, there are three formats of debug information: COFF, CodeView, and Program Database, COFF being the oldest one, where debug info structures are referenced by IMAGE_FILE_HEADER (symbols) and section headers (line numbers), while the latter two have their contents described in a different place, debug data directory.

To sum up the documentation, long section names (along with the string table enabling them) are a feature of object files but not executables, while the built-in symbol table referenced by the IMAGE_FILE_HEADER header is deprecated altogether.

Needless to say, the way shim deals with long section names and debug information is a somewhat non-standard workaround nowadays and I have not encountered such files before. However, some people did. For example, this project parses COFF symbol tables located inside PE files; its author, Alexander Hanel, writes: “This project was created when I became interested in what attributes could be extracted from PE files compiled with GCC”. In my defense, rock protects its inhabitants from the elements and coconut avalanches; all and all, it is not the worst place to live under.

Finally, we can locate cert_table the right way. The code below becomes reproducible once coffcoff is replaced with my version of the library (I modified the original project a little to make it convenient for the purposes of this experiment).

1

2

3

4

>>> [ e for e in coff.entries if e["name"] == b"cert_table" ][0]["section_number"]

6

>>> [ e for e in coff.entries if e["name"] == b"cert_table" ][0]["value"]

0

Like in ELF-related structures, COFF section indices are 1-based, therefore cert_table is located at an offset of 0 from the beginning section pe.sections[5], which is our old friend .vendor_cert, otherwise known as /26. All that remains to be done is to read the certificate and then use it to verify grub’s signature. Both tasks having been completed already (in the first section), I consider our work done and dusted!

Conclusion

In this post, I showed how a Linux shim verified that the second-stage bootloader was genuine and had not been compromised before passing control to it, while figuring out inner workings of UEFI binaries developed with the help of gnu-efi. My hope is that this approach was helpful for those of my readers who like learning through hand-on experience.

For UEFI developers, I am afraid, this post was not of much use, apart for maybe providing an opportunity to enjoy a little snigger at my struggles, if one is into this sort of pastime.

– Ry Auscitte

References

- Kevin Tremblay, UEFI Signing Requirements, Microsoft Tech Community

- UEFI Shim Loader, Commit 3beb971b10659cf78144ddc5eeea83501384440c

- Windows Authenticode Portable Executable Signature Format

- List of File Signatures, Wikipedia

- Ero Carrera, pefile: a Multi-Platform Python Module to Parse Portable Executable (PE) files

- Eli Bendersky, pyelftools: Parsing ELF and DWARF in Python

- Signify: Module to Generate and Verify PE Signatures

- Ignacio Sanmillan, Executable and Linkable Format 101. Part 2: Symbols

- Linker and Libraries Guide, Oracle Documentation

- PE Format, Microsoft Docs

- David Mosberger, Building EFI Applications Using the GNU Toolchain, Part 2: Inner Workings (2007)

- David Rheinsberg, Goodbye Gnu-EFI!, Dysfunctional Programming

- Michael Matz, Jan Hubička, Andreas Jaeger, Mark Mitchell, System V Application Binary Interface, AMD64 Architecture Processor Supplement, Draft Version 0.99.7

- 2 Language Standards Supported by GCC, Using the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC)

- Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) Specification, Release 2.10 (Aug 29, 2022), UEFI Forum

- Oleg Starodumov, Generating debug information with Visual C++

- Alexander Hanel, coffcoff: COFF Portable Executable Symbol Table Parser

- COFF: Symbol Table, DJGPP COFF Spec

- ld(1) - Linux man page

- Ry Auscitte, A Tale of Omnipotence or How a Windows Update Broke Ubuntu Live CD (2022), Notes of an Innocent Bystander (with a Chainsaw in Hand)